My favourite posts from 2025

They might - or might not - be yours

As I said when last I wrote a roundup post, in January 2025, this is a self-consciously idiosyncratic newsletter. I’m enormously grateful to the surprisingly large group of readers who have committed to pay for it, but don’t intend to take them up on their offer. As a matter of policy, I politely decline to engage in the kinds of reciprocity with other newsletters that can help build friendly relations, and I try to pay no systematic attention to eyeball counts. The reasons for these behaviors are largely self-centered. I want to write about what genuinely interests me, and to have a relationship with readers and other writers based on free exchange rather than implied obligation.

Hence, this too is a self-centered post! Rather than highlighting the pieces that got high readership or lots of feedback, I want to present the posts that from 2025 that I personally found useful to write. They build on the ideas of other people, but point towards a broader set of concerns that I am still trying to articulate in a semi-coherent way. So rather than dwelling on the bits that I liked about them, I will talk about how they contribute to what this newsletter is trying to do, how they fit into existing conversations, and where those conversations might go next.

In order of publication date:

#1 - We’re Getting the Social Media Crisis Wrong

This was my first substantial post of 2025. It makes a simple claim, but one that I’m still trying to work out properly.

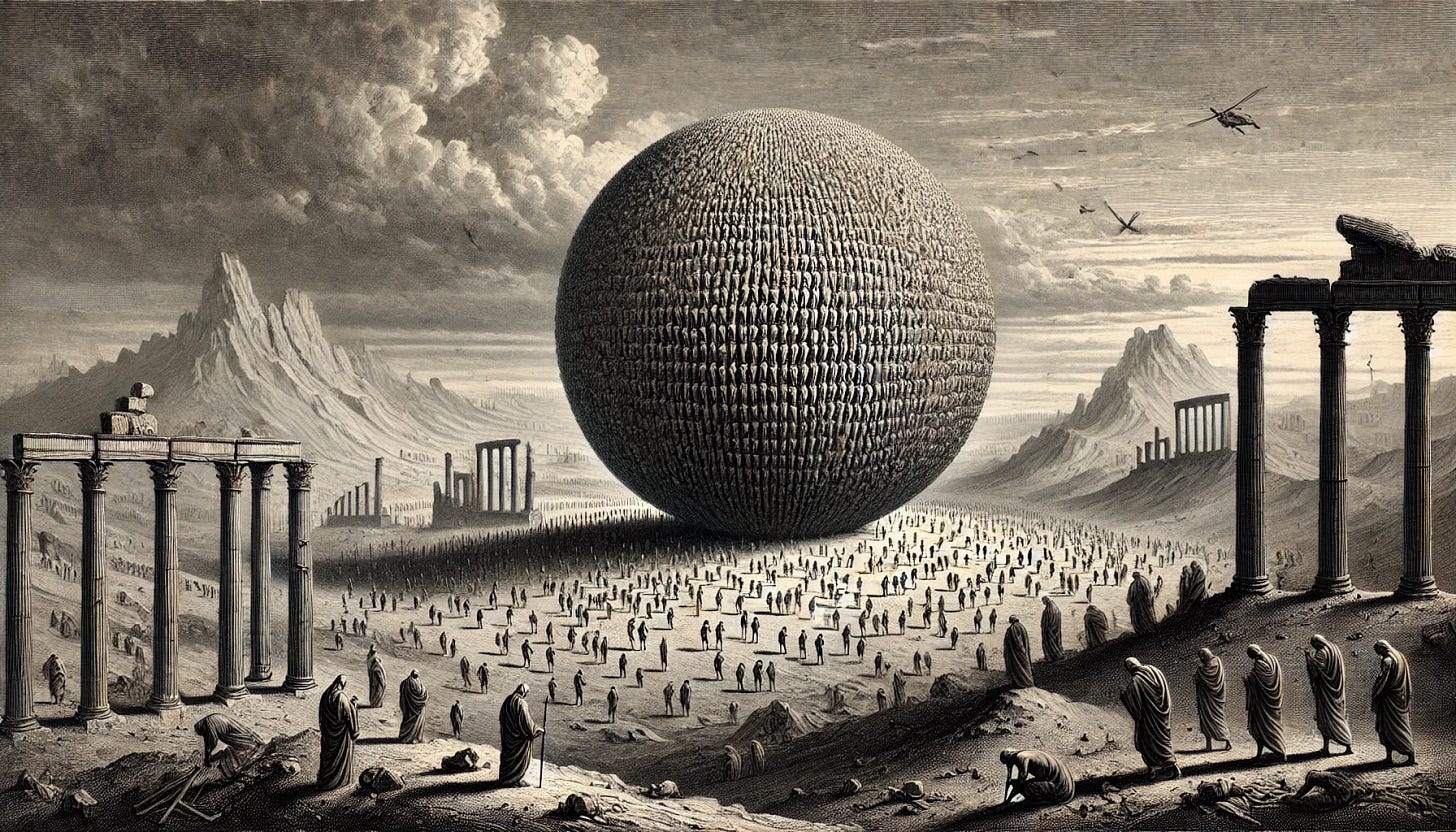

We tend to think about the informational crisis of democracy in individual terms, and to focus on individual solutions: training people e.g. to identify disinformation and misinformation. But this crisis is better thought of collectively. Rather than focusing on the frailties of individual citizens, we should be looking at the problems of democratic publics. Our publics are malformed in part because they build on and perpetuate incorrect understandings of what other citizens believe.

The implication is that we need to pay more systematic attention to the relationship between what might be called technologies of representation and publics. Publics do not magically manifest themselves in transparent ways - they are mediated through social and actual technologies such as voting, opinion polls, social media feeds, and, increasingly, soi-disant AI.

Here, I am riffing on the ideas of Hanna Pitkin (mediated through conversations with Nate Matias), Andy Perrin and Katherine McFarland and Kieran Healy and Marion Fourcade. Hahrie Han and I have written a piece on AI and Democratic Publics that begins to lay out a broader version of this argument. As Cosma Shalizi pointed out to me later, the newsletter does overemphasize the importance of individuals who are designing the algorithms that shape new publics: malformed publics are perfectly capable of building themselves without Elon Musk putting his thumb on the scale.

Actually doing something about all of this will require a much better understanding of how technologies of representation intersect with the ways that humans think. The post also builds on work that Hugo Mercier, Melissa Schwartzberg and I have done to sketch out an initial agenda for how to do this. Samuel Bagg has recently written an incredibly helpful overview of academic research and thinking about these questions that points in a broadly similar direction; see also his recent conversation with Dave Roberts.

#2 - Absolute Power Can Be a Terrible Weakness

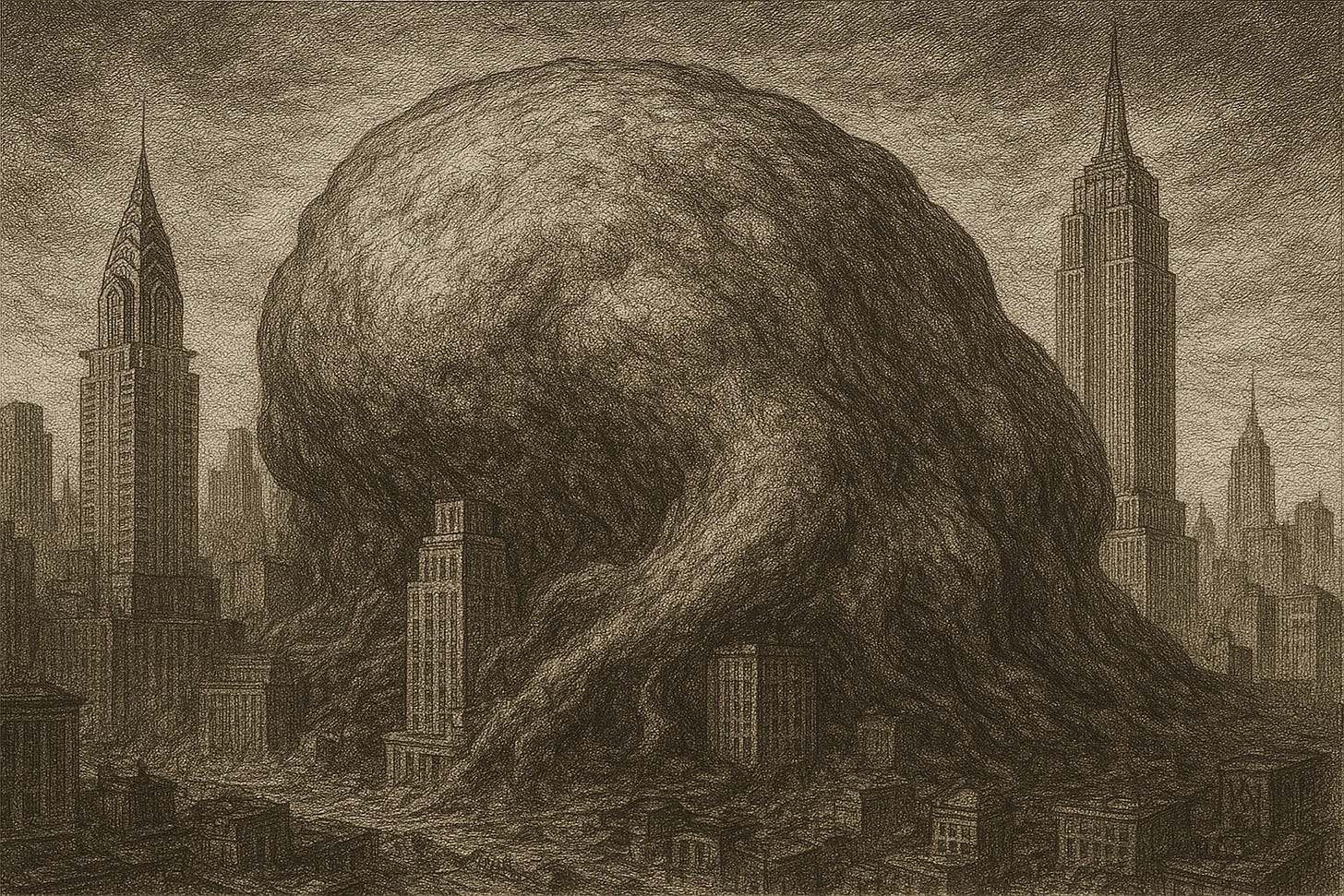

I wrote this post on the train from DC to Baltimore, but was only able to do so quickly because I’d been thinking about it for years. It builds on the ideas of Russell Hardin, who was one of the great theorists of collective action, and also a scholar of David Hume (I strongly recommend his book on Hume).

Hardin has a valuable short essay on the relationship between power and social coordination. This, in turn, suggests a theory of the respective strengths and weaknesses of would-be tyrants and civil society in situations of democratic breakdown.

Hume proposes that tyrants too, depend on social power and influence. They want to create an impression of inevitability, in which everyone accepts that the tyrant is going to win, and have self-interested reasons to jump in on the side of the winning coalition. Civil society can coordinate against the tyrant, but coordination is really hard! The best way for civil society to coordinate is not to generate an expectation of inevitability, but a shared understanding that politics is in play, and that they can succeed in pressing back against incipient tyranny if they get out and do things together to push back.

I think that this was a useful essay in getting Hardin’s and Hume’s ideas out into the world. It also generated (with great editing and restructuring) a New York Times opinion piece that people have told me was helpful in generating a common understanding, although I think that would have come anyway, as people actually began to get out on the ground.

I’m not the right person to turn these loose notions into serious models, but I’m grateful to Filipe Campante for pointing to “global games” as the technique that might most plausibly allow you to do this. It might also be interesting and useful to turn this into an actual boardgame, perhaps like Root, which Thi Nguyen describes as a “completely asymmetric game” about political power struggle, “where each different position has totally different goals and totally different mechanisms.” That might help people understand the dynamics in a practical and concrete way, though again I’m not the right person to to do this.

What I can do, and hope to do more of, is to write about how Hume and other people who are usually treated as classical liberals, provide valuable lessons for the left, centrist liberals, and the actually-democratic right. I’m reading Laura K. Field’s book on intellectuals and Trump at the moment. One of the lessons I take from it is that the right’s unmooring from the ideas of people like Hume has had terrible and pernicious consequences. This has been especially visible in Silicon Valley, but has been important elsewhere. Loosely similar notions to Field’s led me to write this post on Ernest Gellner; further pieces on Gellner’s sometime-friend, sometime-antagonist Karl Popper, and on Gerald Gaus’s fascinating posthumous book on the open society and its complexities will be coming sooner or later.

#3- Brian Eno’s Theory of Democracy

This post comes at the problems of democracy from a different but complementary angle from the first two. It asks how we might think coherently about democracy as an adaptive system, and suggests that an essay by Brian Eno provides a very useful starting point, even if it doesn’t mention the word ‘democracy’ once.

The problem is as follows: that the kinds of democracy we have don’t seem to be working, either in representing people in satisfactory ways, or in responding to a world that is far more complex and threatening than existing institutions are geared to handle. Eno offers a set of design principles for music, which apply remarkably well to other forms of social organization too, including democracy. When you are in a complex environment, you want institutions that are capable of generating new experimental ways of doing things, and building on the variations that seem to work.

This is, as Eno explicitly says in the essay, a cybernetic understanding of design, along the lines proposed by Stafford Beer. Unsurprisingly, it fits well with Dan Davies’ ideas about why large scale organizations and modes of economic policy making are increasingly dysfunctional, which revive Beer Thought for the early-to-mid 21st century.

Dan describes how Allende, when asked what was the ultimate cybernetic control system for society, pointed back to ‘the people.’ Equally, as the social media crisis post suggests, Allende’s dictum begs the question of how ‘the people’ articulates its own views and perspectives. And so back to democratic publics. One way is to build entirely new approaches to democracy. Another is to take existing institutions - such as political parties - and ask how they can be made more adaptable and responsive in a changed attention economy. Something like this intuition pops up in this Ezra Klein and Chris Hayes conversation about Zohran Mamdani. Can you bring together an experimentalist approach to policy with a new kind of attention politics?

I’ll be writing more on this this year, both in academic form with Margaret Levi (we want to ask how democratic experimentalism and social science notions about the experimental method fit together), and in this newsletter. I think the fights between left and moderates in the Democratic Party obscure a more fundamental set of arguments about experimentalism, which I’d like to bring to the fore.

The fundamental motivation for writing about this is that people who talk about democracy are often not strong at understanding the problems of institutional design in a unpredictable world. That is not the body of ideas that they are trained to draw from or to contribute to. People who are actually trying to do stuff in the world are somewhat better, because they have to be, but not nearly as good as they might be if there was a more organized conversation. It would be great if we had a more explicit body of work, ideas and examples that people could draw on, and Eno’s pithy, lovely essay is one way to get people thinking in different ways than they usually do.

#4 - Understanding AI as a Social Technology

This is another effort to build coherent debate where it is lacking, riffing on the ideas of others (in particular, Alison Gopnik, James Evans and Cosma Shalizi). Earlier this year, we wrote an article arguing that we needed to think about AI (emphasizing LLMs, diffusion models and their cousins) as social and cultural technologies rather than agentic intelligence in the making. We felt that a lot of very important questions about social and cultural consequences were being left to one side, because they did not fit into arguments about When AGI Is Coming And What It Means.

This post provides a downpayment on what it might mean to think of AI as a social technology in particular. It suggests that AI is another social shock in the long series of shocks that are the Long Industrial Revolution. When we look at the Industrial Revolution, we tend to overemphasize the technologies themselves, and underestimate the social, economic, political and organizational changes that went along with them. That is likely a mistake.

The post is rather stronger on exhortatory statements about What We Must Do, Comrades, If We Are To Be Real Social Scientists than concrete proposals for how we ought do the things that ought be done. There will be a paper with Cosma Shalizi, sooner rather than later all going well, which is intended to provide a more concrete starting point for bridging the social sciences and computer science so that each can better understand the social consequences (and, indeed, nature) of AI. The paper will likely build on some version of the ideas of Herbert Simon, who managed somehow to make seminal contributions to AI, economics, administrative science and cognitive science, all at the one time. So more on this soon.

#5 - Large Language Models As The Tales That Are Sung

I happened upon the perfect illustration for this piece by accident. It’s a papercut by Hans-Christian Andersen, in which the themes of fairytales repeat and exfoliate, with tiny variations caused by the material and cutting. That aptly illustrates an argument about why LLMs more closely resemble cultural systems of production like fairytales than most technologists suppose. Albert Lord’s The Singer of Tales is the classic account of how such cultural systems of production work.

This certainly isn’t the article that brought in most readers, but it is the piece that I am happiest about having written last year. It helped me articulate things that I had wanted to say but couldn’t figure out how to. As with pretty well everything else I have written, it borrowed heavily from other people. The core intuitions about structure came from Cosma Shalizi and Leif Weatherby, filtered through the broader arguments about AI as a cultural technology that I’ve already mentioned. Others than Cosma and I have noticed the strong similarities between LLMs and the kinds of structures of story telling that Lord describes.

But there is also something deeper and more personal in there too. Gene Wolfe’s books have shaped me in ways I find difficult to describe; especially his Book of the New Sun. For years, I have been trying to articulate how his understanding of story (which is attentive to the problems of structure and predictability that LLMs raise) could help us think about new technologies. I’ve tried before and failed. This time, I feel that I’ve succeeded better, by putting Wolfe (a Catholic humanist who was also an engineer) in conversation with a kind of structuralism that doesn’t dismiss the importance of human intention.

I’d like more people to read Wolfe, and not just because I find current humanist debates about AI frustrating. He was one of the greats. I’d also like to see more AI enthusiasts pay attention to culture as generative structure, to broaden their theoretical vocabulary for understanding technologies like AI. I’ll try to write soon about this conversation between Tyler Cowen and Alison Gopnik, where Tyler, who is more interested in culture than most economists, nonetheless seems to me to radically underestimate its scope and importance, and hence to mistake what is Alison is saying about AI as a cultural technology.

These are the posts from 2025 that I found most useful for my own self-centered purposes. I write this newsletter to build a kind of nexus of conversation that draws together a small number of themes, ideas and people that I think are complementary and important. I’ve tried to explain how some of what I’ve written speaks to these themes, ideas and people, to pull them together and suggest ways in which the conversation might go from here. Thanks to all, and best wishes for 2026!

All great posts that helped me as, an economist, understand AI and power better.

On the global games aspect an interesting reference is this paper by a friend ( http://www.toniahnert.com/WakeUpCall.pdf ).

Basically in the model a change in regime on one country causes a wake up call in another country which becomes more sensitive to a regime change as a result. Your tyrant post made me think of it since he used to present it by giving the Arab Spring as an example of a wake up call event in his model.

That exchange between Gopnik and Cowan struck me as a good example of what happens when AI as cultural technology gets a hearing in the broader AI discourse.

Ben Recht has an essay on Arg Min that revisits Neil Postman's 1988 essay “Social Science as Moral Theology.” This Postman line gets at the problem.

“There is a measure of cultural self-delusion in the prevalent belief that psychologists, sociologists, anthropologists, and other moral theologians are doing something different from storytelling.”

The problem exists in reverse, too. How many qualitative methodists dismiss counting and measuring as just a bunch of counting and measuring? It seems to me the divide between storytellers and counters needs to be overcome in order to get a useful theory of large language models.