We're getting the social media crisis wrong

The bigger problem isn't disinformation. It's degraded democratic publics

This post lays out some ideas that I’ve been thinking about for a long while. You should treat my claims with appropriate skepticism - I’m saying that a lot of public thinking and academic research about social media is chasing after the wrong target, on the basis of (a) my idiosyncratic reading of social theory, and (b) my partial understanding of current events. But at the least, my approach provides a superficially coherent account of how the relationship between social media and democracy is changing in the U.S. and other countries.

Over the last few weeks, we have seen Elon Musk transforming X/Twitter into a kind of deranged parallel universe out of a Philip K. Dick novel, in which the political realities of the US, UK and Germany are re-arranging themselves around the obsessions of an unelected individual. Now, Mark Zuckerberg seems to be taking the guardrails off Meta’s social media services.

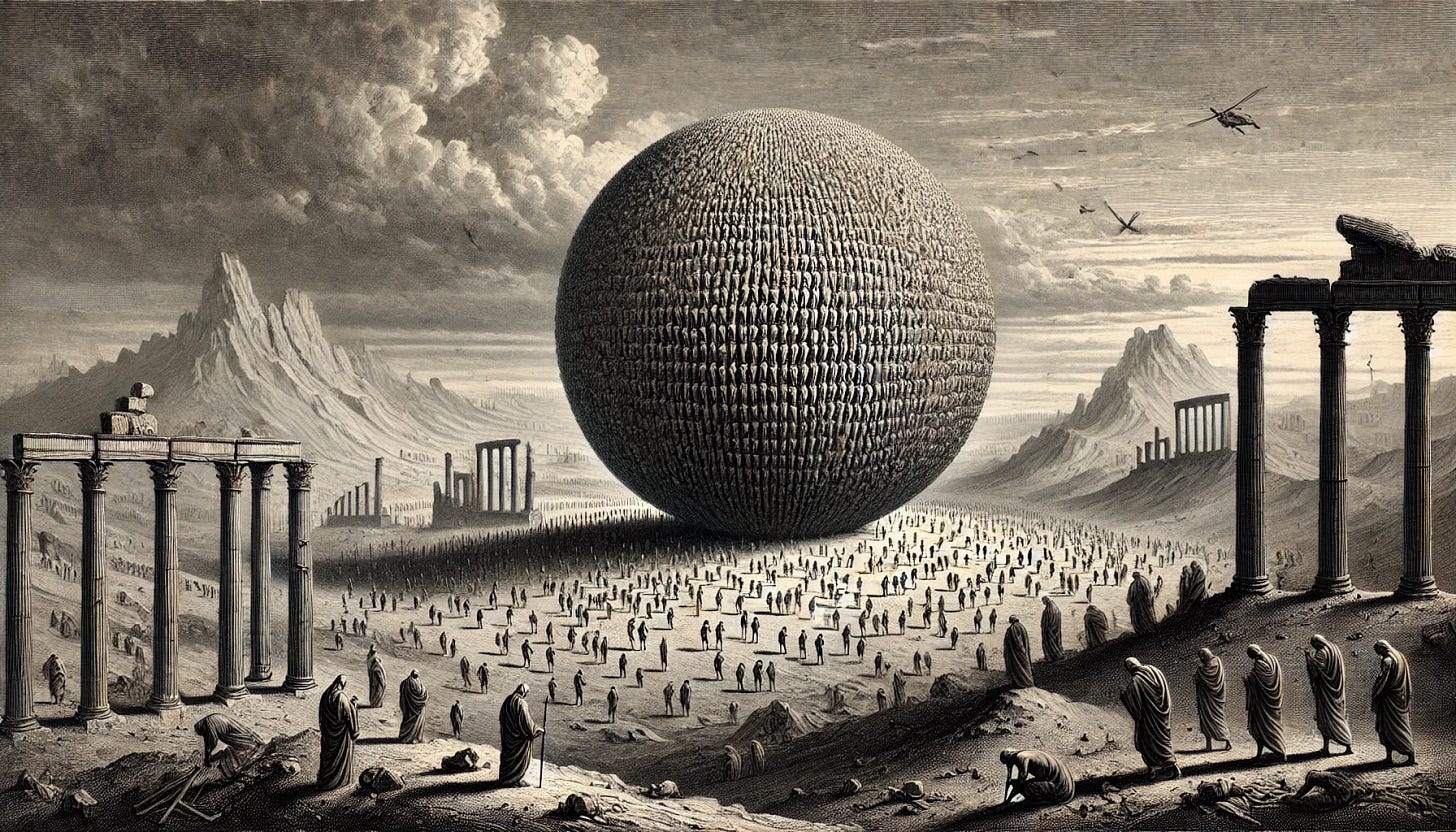

My explanation of what is happening is this. We tend to think of the problem of social media as a problem of disinformation - that is, of people receiving erroneous information and being convinced that false things are in fact true. Hence, we can try to make social media better through factchecking, through educating people to see falsehoods and similar. This is, indeed, a problem, but it is not the most important one. The fundamental problem, as I see it, is not that social media misinforms individuals about what is true or untrue but that it creates publics with malformed collective understandings. That is a more subtle problem, but also a more pernicious one. Explaining it is going to require some words. Bear with me.

*****

The fundamental problem is this: we tend to think about democracy as a phenomenon that depends on the knowledge and capacities of individual citizens, even though, like markets and bureaucracies, it is a profoundly collective enterprise. That in turn leads us to focus on how social media shapes individual knowledge, for better or worse, and to mistake symptoms for causes.

A lot of argument about democracy - both in public and among the academics who inquire into it - makes heroic claims about the wisdom and intelligence of individual citizens. We want citizens who are wise, well informed and willing to think about the collective good. Sometimes, we even believe that citizens are all these things.

The problem is that actual individual citizens are biased and, on average, not particularly knowledgeable about politics. This mismatch between rhetoric and reality has created opportunities for a minor academic industry of libertarians and conservatives arguing that democracy is unworkable and that we should rely instead on well informed elites to rule. The problem with this elitist case against democracy is that elites are just as biased, and furthermore are liable to use their greater knowledge to bolster their biases rather than correct them (for the extended version of this riposte, see this essay by Hugo Mercier, Melissa Schwartzberg and myself). The problem of human bias goes all the way down.

So what can we do to ameliorate this problem? Making individuals better at thinking and seeing the blind spots in their own individual reasoning will only go so far. What we need are better collective means of thinking. As Hugo, Melissa and I argue here (academic article, but I think fairly readable), much of the work on human cognitive bias suggests that people can actually think much better collectively than individually, offering prospects for a different understanding of democracy, in which my pig-headed advocacy for my particular flawed perspective allows me to see the flaws in your pig-headed arguments and point them out with gusto, and vice versa, for the general improvement of our thought.

This is a particular version of an argument that is made more generally by Herbert Simon. There are sharp limits to individual human cognition, but we have invented collective means to think better together. Brad DeLong has a nice phrase for the specific advantage of the human species - “anthology intelligence” - which captures this. Markets, bureaucracies, and indeed democracy can all serve as collective means of problem solving and compensation for individual deficiencies, under the right circumstances. But the qualifying phrase, ‘under the right circumstances,’ is key. All of these institutional forms have failure modes.

To understand the particular success and failure modes of democracy, it is better not to focus on individual citizens, but on democratic publics. Democracy is supposed to be a system in which political decisions are taken not by kings, or dictators, but by the public, or by representative agents that are responsible to the public and can be removed through elections or similar. In principle, then, the public is the aggregated beliefs and wants of the citizenry as a whole.

The problem is that we have no way to directly see what all the citizens want and believe, or to make full sense of it. So instead we rely on a variety of representative technologies to make the public visible, in more or less imperfect ways. Voting is one such technology - and different voting systems tend to lead to quite different manifestations of the public. “First past the post” systems like the U.S. and United Kingdom tend to produce publics in which political contention is channeled through competition between two opposed parties, as opposed to many smaller parties.

Opinion polls are another. They now seem quite natural to us as a gauge of public opinion, but as Andy Perrin and Katherine McFarland argue, they seemed strange and unnatural when they were first introduced.

More importantly, all these systems are not just passive measures of public opinion but active forces that rework it. As Perrin and McFarland say, “Publics are evoked, even shaped, by [the] techniques that represent them.” Human beings are coalitional animals. We appear to have specialized subsystems in our brain for understanding what the group politics are in a given situation; who is opposed to who, and what the opportunities are.

In Perrin and McFarland’s example, when Republicans said in polls that Barack Obama was a secret Muslim, they did not believe this claim in the same way that they believed that water was wet. Instead, their claim had some of the qualities of what Hugo and Dan Sperber call a “reflective belief,” and some of the qualities of a shibboleth - something that you know you are supposed to believe, and publicly affirm that you believe but might or might not subscribe to personally.*

In short, the technologies through which we see the public shape what we think the public is. And that, in turn, shapes how we behave politically and how we orient ourselves. We may end up believing - in a highly specific way - in things that we know we are ‘supposed’ to believe, given that we are Republicans or Democrats, Conservative or Labour Party members. We may end up not believing these things, but also declining to express our actual beliefs publicly, because we know we’re not supposed to believe whatever it is that we privately think. The coalitions that we create, the political battles that we imagine ourselves as engaged in, may also depend on the technologies and the particular fights and issues that they highlight.

This can, under the right circumstances, be roughly to the good. Coalitional politics and disputes are inevitably messy and contentious - but they can be turned towards useful ends. When there are moderate political incentives towards error correction (people feel some obligation to revise their most stupid views in response to well-aimed criticism), small-n pig-headed contention can scale up into forms of competition in which different parties battle it out to provide some rough version of the public good. That has its own problems, but given the ways in which human brains work, it is probably as good as we can reasonably hope to get. It can also turn bad, when pig-headedness feeds on itself and becomes self-reinforcing.

Bringing this all together, the technologies through which we see the public shape how we understand it, making it more likely that we end up in the one situation rather than the other. As you have surely guessed by now, I believe Twitter/X, Facebook, and other social media services are just such technologies for shaping publics. Many of the problems that we are going to face over the next many years will stem from publics that have been deranged and distorted by social media in ways that lower the odds that democracy will be a problem solving system, and increase the likelihood that it will be a problem creating one.

The example that really made me think about how this works has nothing much to do with democracy or political theory. It was the thesis of an article published in Logic magazine in 2019, about Internet porn. The article’s argument is that the presentation of porn - and people’s sense of what other people’s sexual interests are - is shaped by algorithms that respond to the sharp difference between what people want to see and what people are willing to pay for. The key claim:

a lot of people .. are consumers of internet porn (i.e., they watch it but don’t pay for it), a tiny fraction of those people are customers. Customers pay for porn, typically by clicking an ad on a tube site, going to a specific content site (often owned by MindGeek), and entering their credit card information. … This “consumer” vs. “customer” division is key to understanding the use of data to perpetuate categories that seem peculiar to many people both inside and outside the industry. … Porn companies, when trying to figure out what people want, focus on the customers who convert. It’s their tastes that set the tone for professionally produced content and the industry as a whole.

The result is that particular taboos (incest; choking) feature heavily in the presentation of Internet porn, not because they are the most popular among consumers, but because they are more likely to convert into paying customers. This, in turn, gives porn consumers, including teenagers, a highly distorted understanding of what other people want and expect from sex, that some of them then act on. In my terms, they look through a distorting technological lens on an imaginary sexual public to understand what is normal and expected, and what is not. This then shapes their interactions with others.

Something like this explains the main consequences of social media for politics. The collective perspectives that emerge from social media - our understanding of what the public is and wants - are similarly shaped by algorithms that select on some aspects of the public, while sidelining others. And we tend to orient ourselves towards that understanding, through a mixture of reflective beliefs, conformity with shibboleths, and revised understandings of coalitional politics.

This isn’t brainwashing - people don’t have to internalize this or that aspect of what social media presents to them, radically changing their beliefs and their sense of who they are. That sometimes happens, but likely far more rarely than we think. The more important change is to our beliefs about what other people think, which we perpetually update based on social observation. When what we observe is filtered through social media, our understandings of the coalitions we belong to, and the coalitions we oppose, what we have in common, and what we disagree on, shift too.

*****

This leads to a different theory of what is wrong with social media than the usual one, although there is some overlap (a lot of the research that has been done is still useful). If we think that the big problem is disinformation, which might persuade individuals that what is false is in fact true, we are likely to look to one set of remedies. If we think of the problem as malformed publics, then we are in much bigger trouble, without any very obvious technical fixes. Any possible solutions involve collective politics in a world where collective politics are only getting harder.

Over the last two weeks, Elon Musk has used Twitter/X to derail a Congressional budget resolution (writing “Vox Populi, Vox Dei” after he won), to reshape the political debate in the United Kingdom around a two decades old scandal so as to heighten tensions around Muslim immigration, and to elevate the German far-right AfD party as the only solution to Germany’s problems. This morning, Mark Zuckerberg announced that Facebook is moving away from “censorship mistakes,” removing restrictions on “gender and immigration,” and allying with Trump to “push back against foreign governments” (i.e. the EU) that want “American companies to censor more.” These moves are reshaping politics so that they center around the issues that Musk cares about, and that Zuckerberg either cares about or sees as politically convenient to his interests.

The resulting problems are not primarily problems of disinformation, though disinformation plays some role. They are the problems you get when large swathes of the public sphere are exclusively owned by wannabe God-Emperors. Elon Musk owns X/Twitter outright. Mark Zuckerberg controls Meta through a system in which he is CEO, chairman and effective majority owner, all at the same time. What purports to be a collective phenomena; the ‘voice of the people;’ is actually in private hands; is, to a very great extent shaped by two extremely powerful individuals.

Musk and Zuckerberg are different individuals, with different relationships to their platforms. I expect that the distortions that they impose on their publics will be quite different too.

Specifically: Musk directly and repeatedly intervenes to ensure that everything revolves around him, through an algorithm that privileges his posts and pile-ons, through revocations of privileges for those who challenge him, and other means. And he posts incessantly. The result is that X/Twitter is a Pornhub where everything is twisted around the particular kinks of a specific, and visibly disturbed individual. Whatever Musk wants, as the Voice of God, may or may not become the Voice of the People, but is probably what the people are going to end up talking about, whether they want to or not. This is what gives X/Twitter its Philip K. Dick quality - it’s like Dick’s novel Ubik, in which the characters repeatedly find their world being pulled back into the mental patterns of a predatory teenager-turned-existential-vampire, Jory Miller.

Zuckerberg’s social-media-shaped public does not turn around Zuckerberg in the same way. But even so, Zuckerberg is reshaping the algorithms so that some aspects of the public - in particular hostility to immigration, to women and to sexual minorities - will likely come to the fore, while others will recede. The extent to which this reflects his changing personal preferences, as opposed to his willingness to strike a deal with Trump is of secondary importance. It isn’t his personality so much as his interests that are likely to dominate.

Again: none of this is brainwashing, but it is reshaping public debate, not just in the US, but in the UK, Europe and other places too. People’s sense of the contours of politics - what is legitimate and what is out of bounds; what others think and are likely to do and how they ought respond - is visibly changing around us.

That poses some immediate questions. Can democracy work, if a couple of highly atypical men exercise effective control over large swathes of the public space? How can that control be limited or counteracted, even in principle? What practical steps for reform are available in a democracy shaped by the people who you want to reform out of power?

It poses some more general questions too. If you want to work towards a better system of democracy, which is both more stable and more actually responsive to what people want and need, how do you do this? It is easy (I think personally, but I am biased too) to see what is wrong with the public at X/Twitter. It is harder to think clearly about what a healthy public would look like, let alone how to build one.

I don’t have good answers to these questions; just questions. Still, I think they are the questions we need to ask to better understand the situation that is developing around us right now.

* Adam Przeworski describes the following Polish joke from the period of authoritarian rule. “Comrade Secretary delivers a speech on “The Dangers of American Imperialism.” Then all the comrades in the room express their opinions. All, but Comrade Kowalski. It is late Friday night, and everyone wants to go home, yet Comrade Kowalski remains silent. Finally, Comrade Secretary turns to Comrade Kowalski, “Comrade Kowalski, I delivered my speech, all the comrades expressed their opinions, and you, you say nothing. Don’t you have an opinion?” To which Comrade Kowalski sheepishly replies, “Oh, Comrade Secretary, the opinion I do have it. But I do not know if I agree with it.””

I think this is basically right, but I'd add one important detail-- the rise of online communities as a central forum for identity formation and political discourse has necessarily led to the collapse of offline communities organized around place, vocation, etc. that previously facilitated these processes. (Maybe "necessarily led to" is a bit too strong and it's more accurate to say "been accompanied by," but my hunch is that the stronger version is closer to the truth-- people have a finite capacity to participate in various communities and form political conclusions, and the rise of one forum's importance past a certain point necessarily implies the fall of another.) This is really, really bad for the sort of collective democratic thinking that you highlight in the piece as the bedrock for healthy democratic government, since that process relies on each community in the polity first having preferences about issues that are germane to them and then secondly having more-or-less proportional representation so that these preferences are backed at a level appropriate for their prevalence. Here I'm reminded of Sam Rosenfeld and Daniel Schlozman's comment on Know Your Enemy that candidates from both parties have adopted a more national, homogeneous rhetorical affect and set of positions as the parties have been hollowed out. It used to be that a Republican stump speech in Nebraska would sound completely different from a stump speech in New York or Florida, but now you turn on any of the three and they're all talking about trans kids in bathrooms.

I like this explanation as a framework for thinking about why online publics are so poisonous for our political life because it draws attention to several revealing parallels. First off, these forums are accelerating this homogenizing process that Rosenfield and Schlozman were mostly talking about in the context of campaign finance. (I think they may have also discussed social media briefly, but it's been a while since I heard this interview and I'm not sure.) Both of these phenomena untether political elites from a set of positions that they'd otherwise have to represent by raising the salience of other issues, but social media is arguably more dangerous because of how users understand the information they encounter as something natural & intrinsic to their own community rather than something coming from the outside political sphere. Social media thus resembles the Brooks Brothers riot, the Tea Party, and other "astroturfed" political movements and affiliations in American history.

Second, this warping of various communities that were previously sorted into rough political districts by affinity shares some striking similarities to previous dislocations to regional politics that were caused by breakthroughs in information technology-- talk radio, tv, even the printing press if you want to go all Imagined Communities about it. Again, a clear difference here is the apparent "democratized" nature of social media, which is actually financialization slipping in the back as a wolf in sheep's clothing. This new technology is capable of creating new publics and shaping old ones in ways that previous technologies were not in large part BECAUSE each user on one of these platforms believes that they and their peers are actually the actors responsible for creating and shaping the discourse and the platform itself. This feature of social media should draw our attention to past forms of participatory community formation that were brought about by changes in the information landscape (for instance, call-ins on conservative AM radio) as early forerunners of social media that deserve reappraisal. It should also remind us of the letter to the editor or personals section of the now-obsolete local newspaper, again demonstrating how local communities are impoverished and dissolved by the internet and how this dissolution largely operates through economic dislocation.

It's definitely a scary moment! I think that the superficial freedom to move about the internet and associate with one's chosen community did a lot to obscure the ways that this social transformation put so much of our cultural and political life directly in the grasp of the tech companies and oligarchs that organize our virtual spaces. After all, a naive understanding of the internet that ignores the role of algorithms, moderation, and advertising would lead a person to conclude that online we're all just individual actors, making our own individual choices just as we might offline as we move through this new virtual space that Silicon Valley has created to connect the world. This focus on individual agency and the interconnectedness of previously separate actors also suggests that the neoliberal turn has something to do with the widespread adoption of online life in favor of offline life (or maybe it's more accurate to say that the two phenomena feed one another). Like you, I don't know how we might get out of this mess, but the framework you've laid out here is a great start to understanding the problem that has definitely changed my thinking in several important ways.

There are two greats insights in this post:

- First, that the problem with social media is not misinformation.

- Second, the porn analogy about how porn presents people with a distorted view of sex, which in turn can warp people's own views of what they want or should want and how social media does the same with political discussion.

But the last section goes awry. The problem isn't Musk or Zuckerberg. The problem is the structure of the discussion software itself (particularly Twitter and clones like Blue Sky).

Message platforms built on short messages and short replies; that can thread in any different direction; allow unlimited, immediate posting; and support anonymity are inevitably going to descend into snark, incivility, and tribalism no matter who owns or runs them. Platforms like Twitter and Blue Sky are always gong to devolve into showing us the worst version of ourselves in discussions of controversial issues, which in turn warps our view of view of these issues (for exactly the reason captured in the porn analogy).

What is needed for better social media is a discussion platform that helps participants show the best of themselves rather than the worst. Such a platform would:

- Encourage longer posts.

- Encourage people to share what they believe and why rather then responding to the posts of others.

- Have tools in place that prevent discussions from being dominated by the few (who tend to be the most extreme).

- Reward folks who engage constructively.

- Not allow (or at least discourage) anonymity.