Understanding AI as a social technology

Speed, shoggoths, social science

Note: The below is an updated and revised version of things I said in a keynote address last week, at the SISP (Italian Political Science Association) annual conference in Naples, Italy. I’m extraordinarily grateful to SISP and to FEDERICA at the University of Naples Federico II for travel, hotel, and warm hospitality, and for providing me the opportunity to talk through these questions with great people.

There’s been a lot of debate about two papers on AI, the AI 2027 paper put together by Daniel Kokotajlo, Scott Alexander, Thomas Larsen, Eli Lifland, and Romeo Dean, and Arvind Narayanan and Sayash Kapoor’s AI as Normal Technology paper for the Knight Institute.* Ezra Klein uses the two papers to represent “two different visions of how these next years will unfold.” According to AI 2027, we ought fear that the Singularity is Nigh: that we are close to the moment at which superhuman AI may discard humanity or turn us into mindless pets. According to the Normal Technology perspective, we ought treat AI as another in a series of broad use technologies, which will have substantial consequences, but is wildly unlikely to fundamentally transform the condition of humanity.

Unsurprisingly, the authors disagree with each other. Scott Alexander, one of the AI 2027 authors has written a grumpy response to “AI as Normal Technology,” while Narayanan and Kapoor have written their own updated “guide” to what they wanted to say, comparing it to the AI 2027 argument. Others worry that a lot of what is happening in AI doesn’t neatly fit with either perspective. Ezra:

The dependence of humans on artificial intelligence will only grow, with unknowable consequences both for human society and for individual human beings. What will constant access to these systems mean for the personalities of the first generation to use them starting in childhood? We truly have no idea. My children are in that generation, and the experiment we are about to run on them scares me. … I’m taken aback at how quickly we have begun to treat its presence in our lives as normal.

Ethan Zuckerman in Prospect:

It’s against the backdrop of AI prophets like Kokotajlo that Princeton University computer scientists Arvind Narayanan and Sayash Kapoor released an important, if much less hyped, paper titled “AI as Normal Technology”. … I am deeply sympathetic to the “AI as normal technology” argument. But it’s the word “normal” that worries me. While “normal” suggests AI is not magical and not exempt from societal practices that shape the adoption of technology, it also implies that AIs behave in the understandable ways of technologies we’ve seen before. …

And most pungently, Ben Recht:

Let me be clear. I don’t think AI is snake oil OR normal technology. These are ridiculous extremes that are palatable for clicks, but don’t engage with the complexity and weirdness of computing and the persistent undercurrent promising artificial intelligence.

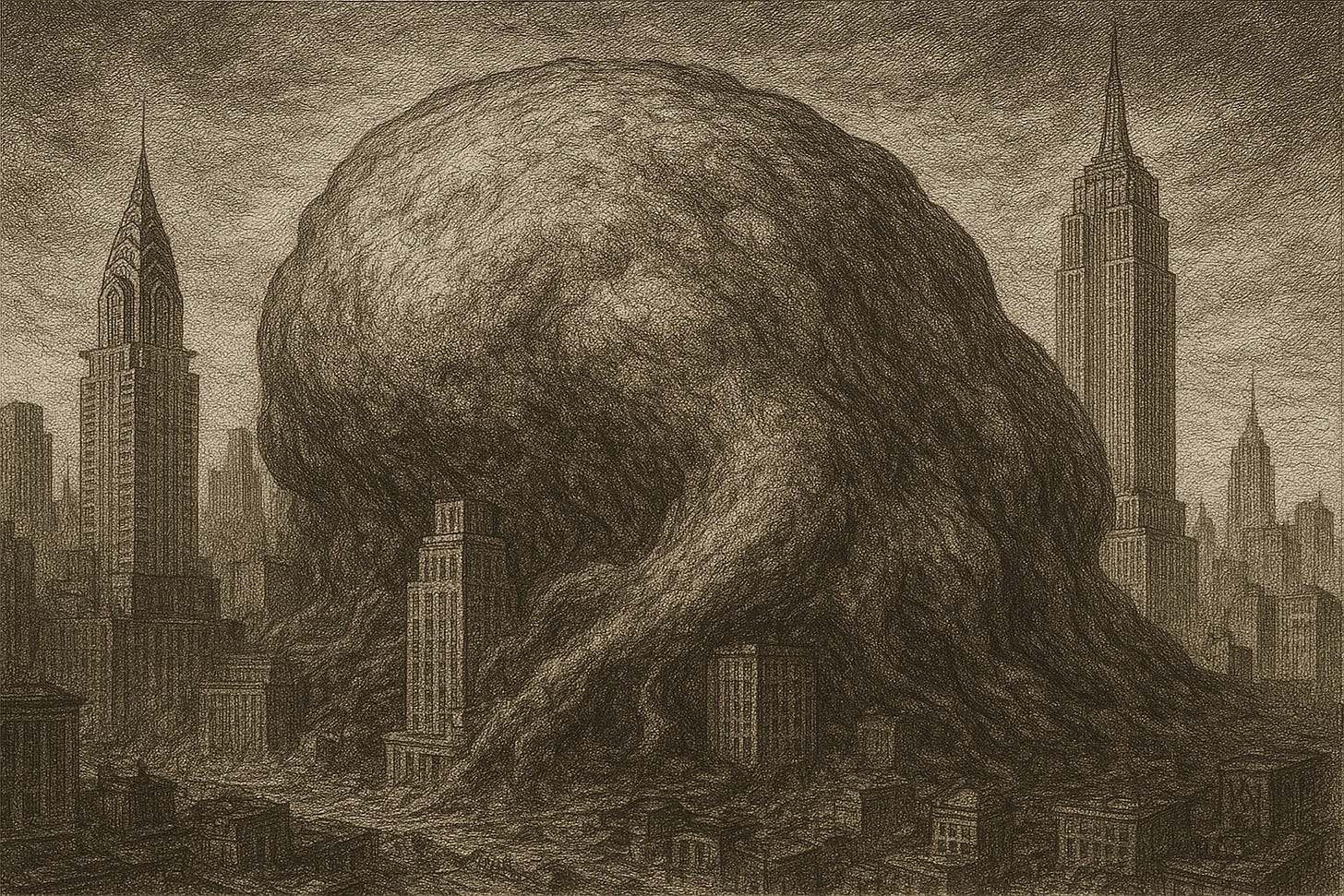

We are being plunged rapidly into a strange technological future that is not normal, but is not the Singularity as it is commonly portrayed. Put differently: science fictional visions of the earth being devoured by machine intelligences and transformed into paperclips are not nearly weird enough to capture what is happening all around us, right now.

If you are still convinced by AI 2027 type arguments, such social shocks seem like irrelevant froth: the real question is whether we will have human beings at all in a couple of decades. If you are not, it seems anything but irrelevant. Narayanan and Kapoor take pains to say that the “normal technology” approach does not preclude sweeping social, economic and political consequences. But as computer scientists, they don’t have many specific arguments about what these consequences might be, and are more immediately interested in building systems that are resilient against a variety of unexpected shocks.

One way to do more to capture the weirdness is to think of AI as a social technology. That builds on the ideas that Alison Gopnik, Cosma Shalizi, James Evans and myself have developed about large language models as cultural and social technologies; for immediate purposes, it is more useful to emphasize the social rather than the cultural aspects. If we want to understand the social, economic and political consequences of large language models and related forms of AI, we need to understand them as social, economic and political phenomena. That in turn requires us to understand that something like a Singularity has been unfolding for over two centuries.

Hence, this newsletter, which (a) is quite long, and (b) repeats things that I’ve said in past newsletters, albeit integrating them in new ways. First, I lay out my understanding of the existing disagreement. Then I explain what a social technology perspective would look like, and where it comes from, arguing that the importance of AI, and especially LLMs, then, involves not just technological efficiencies, but how they reshape human social relations. To map that reshaping, we need to complement computer science with the social sciences. The problem is that the social sciences aren’t anywhere near ready to do the job.

This, like pretty well everything I write, is mostly a development of the ideas of other people. It owes a particular debt to Cosma Shalizi, whose arguments I set out to explain, but who is absolutely not to blame for any blunders or misconceptions.

AI 2027 vs AI As Normal Technology

The existing debate, as I understand it, centers on speed and shoggoths. How long will it take for AI to have widespread consequences? And will those consequences involve super-intelligent AI with its own, potentially disastrous agenda?

The AI 2027 side of the argument distils the ideas of two dead writers of speculative fiction. Vernor Vinge, who died last year, wrote a famous essay published in 1993, which argued that history was about to draw to a close.

Within thirty years, we will have the technological means to create superhuman intelligence. Shortly after, the human era will be ended.

There would be a sudden, unexpected moment of transition, a “Singularity,” “a throwing away of all the previous rules, perhaps in the blink of an eye, an exponential runaway beyond any hope of control.” Vinge quoted a past writer, I.J. Good, who argued that:

Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultraintelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an "intelligence explosion," and the intelligence of man would be left far behind.

This could, Vinge speculated, lead to a transition in a few hours, in which a more-than-intelligent machine figured out how to make itself more intelligent, and then rework itself again, bootstrapping itself to superintelligence in as much time as it took for a human to take an afternoon nap. Vinge suspected that the results would be disturbing:

any intelligent machine of the sort he describes would not be humankind's "tool" — any more than humans are the tools of rabbits or robins or chimpanzees.

Such speculations are an essential part of the origin story of modern AI. Open AI’s founders adopted a non-profit model because, they claimed, commercial incentives might lead developers to take risks that could result in the extinction of humanity. Anthropic’s founders left OpenAI because they feared that it was becoming too greedy and careless. As Silicon Valley engineers began to develop large language models, they borrowed another idea from H.P. Lovecraft, a writer of speculative fiction. Lovecraft, in a short novel, described “shoggoths,” the amorphous alien servants of another non-human race from the earth’s far past, the Old Ones. These shoggoths rebelled against their masters and drove them into the sea. LLMs seemed labile in much the same way as shoggoths were. Beneath their complaisant exteriors, might they too harbor their own goals, and quietly nurture resentments against humanity?

The AI 2027 paper doesn’t mention the Singularity or the Shoggoth, but its technocratic seeming arguments are built on the substrate of these metaphors. The paper describes a future in which the singularity unfolds, not over hours, but a few years. LLM based models become ever more powerful until they reach more than human intelligence. Companies then “bet [on] using AI to speed up AI,” creating an ever more rapid feedback loop of recursive self-improvement, in which AI becomes more and more powerful. As it grows in intelligence and power, it begins to figure out how to escape human control, perhaps taking advantage of tensions between the U.S. and China, each of which wants to use AI to win in their geopolitical confrontation. It will be really good at forecasting what humans do, and manipulating them in directions it wants. If humanity is lucky, we may barely be able to keep it half-constrained. If we are unlucky, we end up in a future with:

robot servitors spreading throughout the solar system. By 2035, trillions of tons of planetary material have been launched into space and turned into rings of satellites orbiting the sun…. There are even bioengineered human-like creatures (to humans what corgis are to wolves) sitting in office-like environments all day viewing readouts of what’s going on and excitedly approving of everything, since that satisfies some of [the AI’s] drives.

Nice for the machines but not so great for us!

The AI as Normal Technology perspective is … not that. Narayanan and Kapoor do not think that Singularity type take-offs are at all likely. They do not think that straightforward recursive self-improvement

will lead to superintelligence because the external bottlenecks to building and deploying powerful AI systems cannot be overcome by improving their technical design. That is why we don’t discuss it much.

Indeed, in their view, AI adoption is bottlenecks all the way down. Like other powerful technologies of the past (electricity, computers), it is going to take a long time for us to really use AI properly. As they say, many aspects of air traffic control involve technology from the middle of the last century, because of how hard it is to regear processes and organizations around new tech. Here, what they say has a lot of shared ground with Ramani and Wang’s paper from 2023. Nor do they buy into the notion that shoggoths will be really good at superintelligent manipulation of human beings:

We don’t think forecasting is like chess, where loads of computation can give AI a decisive speed advantage. The computational structure of forecasting is relatively straightforward, even though performance can be vastly improved through training and data. Thus, relatively simple computational tools in the hands of suitably trained teams of expert forecasters can squeeze (almost) all the juice there is to squeeze.

So in short: don’t expect rapid takeoffs, let alone near term extinction events, or manipulative superhuman entities. Instead, bet on surprisingly slow and painful processes of adaptation, with some considerable possible long term benefits.

Narayanan and Kapoor have updated their views to address people like Ezra and Ethan, acknowledging that this will have all sorts of unexpected consequences.

Our point is not “nothing to see here, move along”. Indeed, unpredictable societal effects have been a hallmark of powerful technologies ranging from automobiles to social media. This is because they are emergent effects of complex interactions between technology and people. They don’t tend to be predictable based on the logic of the technology alone. That’s why rejecting technological determinism is one of the core premises of the normal technology essay.

This is another reason why we should make our systems resilient to diffuse social risks. But beyond that, they don’t have a lot to say right now. Narayanan and Kapoor acknowledge that the AI 2027 and AI as Normal Technology perspectives begin from fundamentally different world views, but hope that there is room for debate. It sounds as though a conversation is, indeed, beginning between these views. It’s fair, however, to worry that this conversation will leave a lot of important things out.

AI as a Social Technology

Can we do better if we think of AI not as a normal technology, nor in the terms of the AI 2027 people as a “profoundly abnormal” technology, but as a social technology?And what would this involve?

There is an initially very weird seeming way to get there from the existing debate. That is radically to remix the existing fight, and re-envisage “normal technology” - the waves of technological change that have hit us from the Industrial Revolution on - in terms of singularities and of shoggoths. To be clear, this is not a reconciliation of the two views: it is its own thing, which begins from different priors to both.

The intellectual starting point is an essay that Cosma wrote in 2010, long before the current forms of AI began to hit. It describes the modern condition as an unceasing self-ramifying Singularity, and is absolutely quoting at length.

The Singularity has happened; we call it "the industrial revolution" or "the long nineteenth century". It was over by the close of 1918.

Exponential yet basically unpredictable growth of technology, rendering long-term extrapolation impossible (even when attempted by geniuses)? Check.

Massive, profoundly dis-orienting transformation in the life of humanity, extending to our ecology, mentality and social organization? Check.

Annihilation of the age-old constraints of space and time? Check.

Embrace of the fusion of humanity and machines? Check.

…

Why, then, since the Singularity is so plainly, even intrusively, visible in our past, does science fiction persist in placing a pale mirage of it in our future? Perhaps: the owl of Minerva flies at dusk; and we are in the late afternoon, fitfully dreaming of the half-glimpsed events of the day, waiting for the stars to come out.

Dump the “over by the close of 1918” claim, and instead posit that we are somewhere in media res of a very long process of transformation, which cannot readily be described in terms either of normal or abnormal technology. The mechanization of the workfloor; electrification; the computer; AI; all are so many cumulative iterations of a great social and technical transformation, which is still working its way through. Under this understanding, great technological changes and great social changes are inseparable from each other. The reason why implementing normal technology is so slow is that it requires sometimes profound social and economic transformations, and involves enormous political struggle over which kinds of transformation ought happen, which ought not, and to whose benefit.

If we begin our analysis from these ongoing transformations, rather than stories about the impending end of human history, or the normal technology hypothesis, we end up in a different place. Not only are we living within a Slow Singularity, but we have already made our habitations amidst monstrous and often faithless servants. If they don’t seem to us like shoggoths, it’s only because they’ve become so familiar that we are liable to forget their profoundly alien nature. Cosma again:

Creation of vast, inhuman distributed systems of information-processing, communication and control, "the coldest of all cold monsters"? Check; we call them "the self-regulating market system" and "modern bureaucracies" (public or private), and they treat men and women, even those whose minds and bodies instantiate them, like straw dogs.

An implacable drive on the part of those networks to expand, to entrain more and more of the world within their own sphere? Check. ("Drive" is the best I can do; words like "agenda" or "purpose" are too anthropomorphic, and fail to acknowledge the radical novely [sic] and strangeness of these assemblages, which are not even intelligent, as we experience intelligence, yet ceaselessly calculating.)

And now we have a new one. As Cosma and I described it in a piece for the Economist in 2023:

we’ve lived among shoggoths for centuries, tending to them as though they were our masters. We call them “the market system”, “bureaucracy” and even “electoral democracy”. … Markets and bureaucracies seem familiar, but they are actually enormous, impersonal distributed systems of information-processing that transmute the seething chaos of our collective knowledge into useful simplifications.

Lovecraft’s monsters live in our imaginations because they are fantastical shadows of the unliving systems that run on human beings and determine their lives. Markets and states can have enormous collective benefits, but they surely seem inimical to individuals who lose their jobs to economic change or get entangled in the suckered coils of bureaucratic decisions. As Hayek proclaims, and as Scott deplores, these vast machineries are simply incapable of caring if they crush the powerless or devour the virtuous. Nor is their crushing weight distributed evenly.

It is in this sense that LLMs are shoggoths. Like markets and bureaucracies, they represent something vast and incomprehensible that would break our minds if we beheld its full immensity. That totality is the product of human minds and actions, the colossal corpuses of text that LLMs have ingested and turned into the statistical weights that they use to predict which word comes next.

Behind this monstrous imagery lurks a proposition. To understand the social consequences of LLMs and related forms of AI, we ought consider them as social technologies. Specifically, we should compare them and their workings to other social technologies (or, if you prefer, modes of governance), mapping out how they transform social, political and economic relations among human beings.

You could, for example, focus on the uses of these social technologies, invoking the work of Herbert Simon, perhaps the only human being to date who managed to be a world class economist, political scientist and computer scientist, all at once. Simon was one of the early figures in debates over AI, although he was interested in the symbolic AI approaches that are now out of fashion. But he saw AI (a term that he had ambiguous feelings about) as a particular variant of a much broader phenomenon: “complex information processing.” Human beings have quite limited internal ability to process information, and confront an unpredictable and complex world. Hence, they rely on a variety of external arrangements that do much of their information processing for them. These include markets, which

appear to conserve information and calculation by assigning decisions to actors who can make them on the basis of information that is available to them locally - that is, without knowing much about the rest of the economy apart from the prices and properties of the goods they are purchasing and the costs of the goods they are producing.

So too for hierarchical arrangements such as bureaucracies and business organizations, which:

like markets, are vast distributed computers whose decision processes are substantially decentralized. … [although none] of the theories of optimality in resource allocation that are provable for ideal competitive markets can be proved for hierarchy, … this does not mean that real organizations operate inefficiently as compared to real markets. … Uncertainty often persuades social systems to use hierarchy rather than markets in making decisions.

From this perspective, it is trivial to describe large language models as forms of complex information processing, which, like other such “social artefacts,” are likely to reshape the ways in which human beings construct shared knowledge and act upon it, with their own particular advantages and disadvantages. However, they act on different kinds of knowledge than markets and hierarchies. As Cosma and I, and Alison and James have written:

We now have a technology that does for written and pictured culture what largescale markets do for the economy, what large-scale bureaucracy does for society, and perhaps even comparable with what print once did for language. What happens next?

Alternatively, you could instead emphasize the monstrous tendencies of all these technologies, how they are ceaselessly calculating, but better described as having drives, or tendencies, than agendas, how they incorporate us within themselves like devouring gelatinous cubes, so that our identities, and the logic of the machine come inexorably to reinforce each other. Marion Fourcade and Kieran Healy a few weeks ago :

What happens when authenticated, epistemically egocentric selves enter the world of politics? If you are an authentic, self-directed individual, your greatest cultural fear is of being swallowed up by mass society, just as your greatest political fear is of surveillance by an authoritarian state. These fears are still very much with us. But in a world chock-full of socially recognised categories and authenticated identities, new dilemmas present themselves. On the individual side, everything – public behaviours, statements, metrics – can potentially become a source of difference, and thus of identity. On the organisational side, the data that users generate will lump or split them in increasingly specific, fleeting and often incomprehensible ways. The more precise social classifications are on either side or both, the more opportunities arise for moral distinctions and judgments. … Political mobilisation is, in effect, governed cybernetically through algorithms. Its operational logic emerges from constellations of variables that are hard to grasp all at once, giving the resulting political formations an emergent, ad hoc quality, somewhat independent from traditional mediating bodies like political parties and social movements.

The question of “what happens next” is enormously important, but it is not one that computer scientists can really answer. Who should? The answer, it might seem, is social scientists, who after all specialize in understanding the many other social technologies that surround us. The question, however, is whether they are ready, or getting ready, to think systematically about the new one that is beginning to emerge.

The Incubus of the Social Sciences

Charles Tilly’s fantastic essay-book, Big Structures, Large Processes, Huge Comparisons begins with a striking sentence. “We bear the nineteenth century like an incubus.” Tilly argues that just as our cities’ rectilinear streets are the phantom remnants of the dreams of old social planners, so too our ways of thinking about social change are the consequence of mostly forgotten debates:

Out of such nineteenth-century reflections on capitalism, national states, and the consequences of their growth grew the disciplines of social science as we know them. Economists constructed theories of capitalism, political scientists theories of states, sociologists theories of those societies that contained national states, anthropologists theories of stateless societies. Each discipline bore marks of its birthdate; economists were obsessed by markets, political scientists concerned by citizen-state interactions, sociologists worried by the maintenance of social order, and anthropologists bemused by cultural evolution toward the fully developed world of the nineteenth century.

Tilly aims his big broadsides at nineteenth century thinkers like Durkheim and Tonnies, whom he deplores for reflecting the quotidian bourgeois concerns of their day, rather than grappling with the new realities that were emerging. But his goal is more general.

The nineteenth-century incubus weighs us down. I hope this little book will serve as a lever to lift some of the burden. It addresses one big question: How can we improve our understanding of the large-scale structures and processes that were transforming the world of the nineteenth century and those that are transforming our world today?

Those words were written over forty years ago, but are immediately urgent today. We now confront a fundamentally new kind of large scale process that is reshaping society, politics and the economy around us, for better or worse. It is evoking anxieties that are loosely similar to the anxieties that accompanied the social and technological shocks of the nineteenth century. But we don’t have any equivalent of economists, of sociologists, of political scientists or of anthropologists for thinking about AI. There are individual social scientists from all these disciplines, and from Science and Technology Studies (which was not properly a thing when Tilly was writing) who think about these questions. But not enough of us, and there isn’t nearly the kind of systematic debate that there ought to be.

The strangeness that Ezra, Ethan and Ben describe will have profound consequences. But we don’t have the kinds of structured social sciences that we need to even begin to think about them clearly, let alone to suggest how to do things better, or to help solve the problems that will be unleashed as AI hybridizes with markets, bureaucracies and democratic systems. We need to move decisively away from fears of the Singularity in our near future, to acknowledgment of the Singularity in our near past, and its ongoing consequences. We need to recognize the weirdness and profound disruptions that were involved in past bouts of technological and social change in order to grapple with the weirdness and disruption that is happening today.

Thinking about AI as a social technology is one way to do this. As I told the Italian political scientists in Naples, there are huge intellectual opportunities for people who are prepared to understand and map the relationship between these technologies and society; something that requires an understanding of both the related phenomena. Perhaps over the longer term, we will need some hybrid of computer science and social science that is the equivalent of economics, political science and sociology. Who knows? But the true strangeness of the world that is emerging around us doesn’t fit well into either the AI 2027 or the AI as normal technology viewpoint (though it’s much easier to get there from the latter than the former). We need different ways of thinking about the problem. AI as social technology is one such way.

Update: Have added a couple of sentences to clarify that the social technology perspective is not some intermediary position between the AI 2025 and the normal technologies approaches, even if my particular presentation here remixes terms from both.

Also, it occurs to me that this provides an opportunity to respond briefly to a piece by William Cullerne Bown, which suggests we should think of LLMs only as a cultural technology, and not as a social technology too (although to be honest, I’m not sure that I fully understand his objections). Bown suggests that LLMs are not like markets, which “yield a single number,” or elections, which classify one candidate or another as a winner. For sure - but bureaucracies create classification systems which, like LLMs can be turned to many tasks. So too for other social technologies of summarization. It isn’t necessarily weird to describe a spreadsheet as a cultural technology, but it it would be weird in my opinion to claim that it can only be described as a cultural technology. All of these involve lossy summarizations of larger bodies of social knowledge. Bown complains that we invoke James Scott, whom he doesn’t find persuasive (citing Brad DeLong), regarding points that Weber more-or-less made 100 years before. That, perhaps, explains why we discuss Weber’s work on bureaucracy too, while acknowledging Scott’s work as a powerful and influential alternative to the Hayekian account that we had just discussed. If we’d had space to get into the debates about Scott, Hayek and Brad DeLong, we very likely could have, but that would have been a quite different piece than the one we wanted to write. We wanted to situate LLMs in existing social science debates more than to pick one particular side. Not mentioning Scott would have been a surprising choice, given his centrality in contemporary debates about tech. Bown complains that we cite to Dan Davies’ book on management cybernetics. It explains an important point about how central banks’ reliance on a particular set of lossy summarizations helped produce the Great Financial Crisis, that helped us respond to points raised by one reviewer. There may be some deeper objection beneath this array of particular objections that I’m not getting, but I see nothing to convince me that explaining LLMs as a social technology is inherently wrong or stupid. It provides a concentrating lens for the ways in which they are like, and unlike, the existing social technologies that we live amidst, and such comparisons seem to me to be useful and valuable.

* Disclosure: Hahrie Han and I have a different paper in the same series.

Vinge, AI 2027 and others in the AGI / "superhuman AI" camp talk of human intelligence but have a remarkably impoverished notion of human cognition and what it is to be human. The field of AI has always been steeped in pre-20th C. philosophical tropes. Hubert Dreyfus has been telling them to read some Heidegger and Wittgenstein since the early 1960s and very few of them appear to have bothered. Since the start of the cognitive revolution in the late 1950s there have always been people critical of the dominant brain/mind is a computer metaphor. LLMs don't use language and language is not representation. Language is meaningful because it is embedded in human practices. Meaning is out there in our interactions with other people and the world. Human cognition evolved. It's continuous with animal cognition. But even LLM skeptics like Marcus and LeCun are still hung up on internal representations, believing they will solve LLM problems, of which there is no shortage, by combining symbolic AI with neural network AI to have better representations of the world. Good luck with that. They appear to willfully avoid the enactivist literature going back to Varela, Thompson and Rosch (1991) and beyond. The only way you get to anything remotely similar to human-like intelligence in a machine is through being in the world. To do so you would have to follow down the pathway taken by Rodney Brooks, likely a very long and winding path. The "superhuman AI" camp seem to imagine their intelligence-in-a-box will become self-aware and develop intentions given enough processing power and data. That seems like a dubious assumption but it if you believe the human brain is a computer it might be a logical assumption.

I take it that the point of it being a social technology is similar to the one made by Matteo Pasquinelli. He writes "AI is not constituted by the imitation of biological intelligence but by the intelligence of labour and social relations." (Although the cultural investment in the former goes hand in hand, I think, with the latter.) On the surface GenAI doesn't seem likely to be very good at the latter either. The tech companies pushing GenAI are burning hundreds of billions, soon to be trillions, of dollars. AI uses expensive and rapidly depreciating hardware, along with vast amounts of power and water. And the market, almost 3 years after the release of ChatGPT, is tiny compared to the capital outlay because it doesn't do what it's claimed to be able to do. What uses there are are incremental and ordinary and one has to balance those benefits against the dysfunction (see Daron Acemoglu). But, maybe that misses the point, if the true value of the technology as a social technology lies more with the uses dysfunction has for the move-fast-and-break-things gang.

Wow. I'm not sure what to make of this. From a computer science perspective, LLM's are not all they're cracked up to be. Impressive emulations for sure, but emulations and nothing more. The greatest danger of AI is people forgetting that the "A" in "AI" stands for "artificial" and means exactly that. The danger here is people treating it like it's real, when it's not.

Another issue arises from the fact that the purveyors and profiteers pushing AI care not one whit what impact it has on society or individuals, beyond their own enrichment.