Davos is a rational ritual

How Europe and Carney disrupted Trump's ceremony of self-anointment

This post tries to combine a conversation I had yesterday (more on that soon) with a piece from Adam Tooze this morning (behind paywall) and two other pieces from Adam and Paul Krugman over the last couple of days. We’re all trying to figure out what exactly happened at Davos, and I think that there is a very useful book that might help explain it. The book is Michael Chwe’s Rational Ritual: Culture, Coordination and Common Knowledge. It’s a game theoretic account of why ritual is important.*

First, Adam and Paul. In his newest piece, Adam talks about the two alternative theories he had of what would happen at Davos this year. One guessed that it would be irrelevant; the other saw it as the place where capital might come together to coordinate against Trumpism.

These two particular theories map onto broader accounts about how Davos (a yearly meeting of very rich and very powerful people, with various hangers on and the odd academic or expert here or there for ornamentation) works. The ‘it doesn’t matter’ argument is closely compatible with the many journalistic and critical accounts of Davos that see it as an empty ceremony, in which people come together to boom out the shared collective wisdom at volume. The ‘capital might coordinate against Trump’ argument maps onto a different, but not entirely incompatible account of Davos as a place where the people with the money exercise their clout over politicians.

But as Adam says, neither is a good explanation of what happened this week.

The weight of Larry Fink and BlackRock added to the attraction of the WEF itself. It secured a truly remarkable turnout of capital of all kinds - asset managers, banks, hedge funds, PE, tech, industry from all over the world. … What was no less striking, however, was the collective public silence of this array in the face of the performance of the MAGA delegation. … The most plausible interpretation is not that this silence implies tacit approval, but rather fear of retaliation and victimization by the administration.

In his earlier post, Adam uses visceral language to describe what that feels like.

I remember the evening before, the stony-faced CEO warning me: “Be clear. Don’t be surprised. When he comes through the door … They will beat up on you. You will squeal. Then they will beat up on you again. You will hurt some more. They don’t mean to kill you. In the end you will settle on a spectrum of terms that they dictate. This is how it works. Time you understood it.”

Yet as he says, something unexpected happened. Adam explains this in terms of convening, staging and acting. You bring a lot of rich and powerful people together, you use media to build a stage that the outside world can see and is likely to pay attention to, and you call on politicians to be actors on that stage. That all creates an opportunity for politicians to go off script, as they did.

As Paul said separately:

Donald Trump and his team clearly went to Davos determined to demean and insult their hosts. It was, one might say, a novel approach to diplomacy: “You’re pathetic, your societies and economies are falling apart, now give us Greenland.” And it worked about as well as you’d expect. Trump may have imagined that the Europeans would cower in the face of his wrath. Instead, they humiliated him. He dropped his latest tariff threats in return for a “framework” that gave the United States essentially nothing it didn’t already have — and left behind a Europe that is finally united in resistance to his bullying.

You could see this shift happening in real time in the public statements of Trump administration officials. So what exactly happened, and how important is it?

This is where I find Chwe’s arguments to be extremely useful. I take two lessons from his book. First, that Davos fits very clearly into his definition of `ritual.’ Second, that rituals are important because they create common knowledge.

What we have seen at Davos over the last few days was an effort by the Trump administration to create new common knowledge in the world, an agreement that Trump was in charge, and that politics revolved around him. That effort has failed because of pushback from politicians, both Europeans who were furious at Trump, and Canada’s prime minister, Mark Carney who gave a quite extraordinary speech. However, the result is most certainly not a decisive victory for Europe, Canada, and the other forces allied with them. Instead, it is one significant moment in a longer story of struggle and contention.

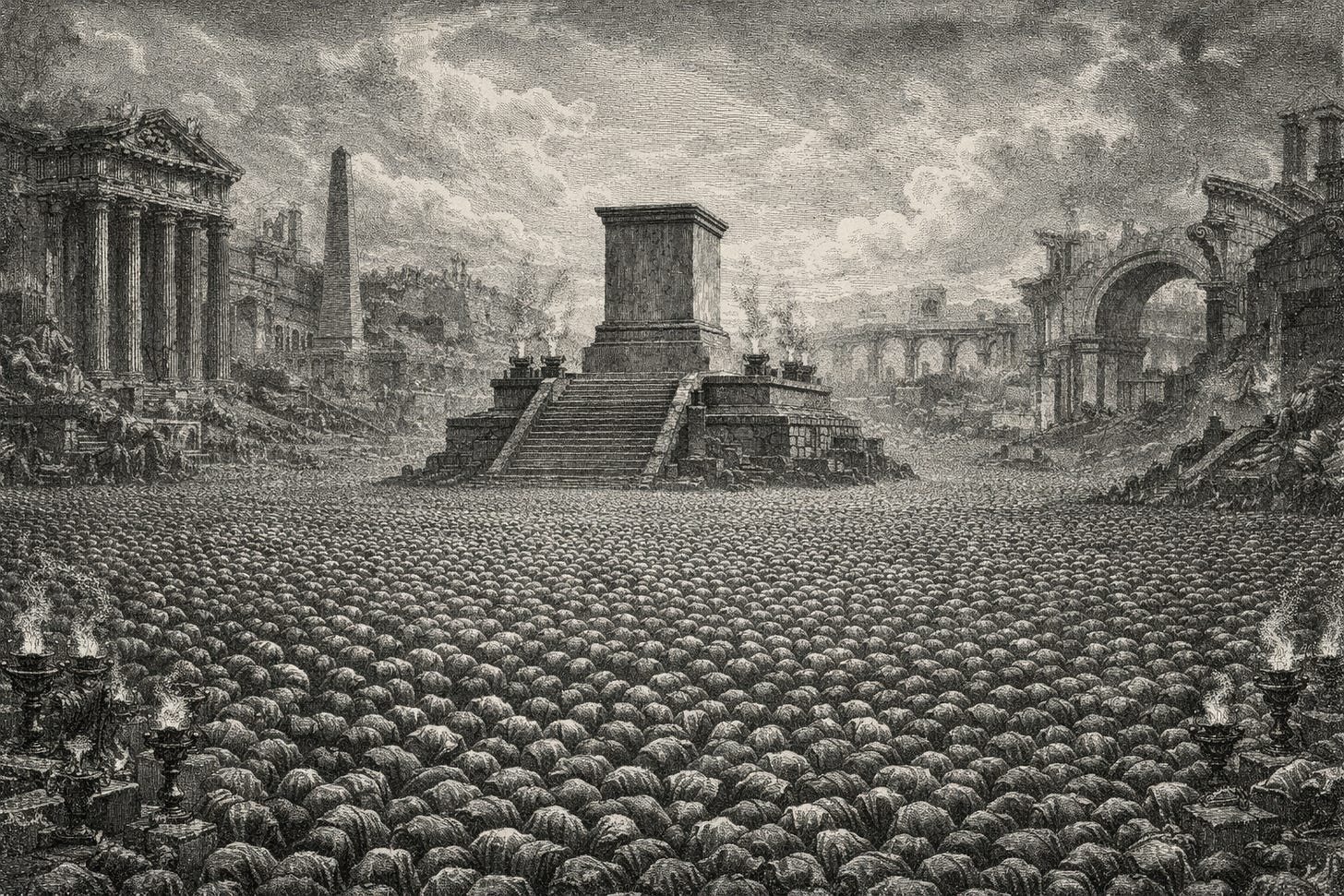

Chwe argues that rituals are about creating coordinated expectations, and that this is why they are often an exercise in power. He quotes Clifford Geertz on ‘royal progresses’ - journeys undertaken by monarchs and their entourages through their countries and hinterlands, which are in large part about creating a shared understanding of who is in charge.

Royal progresses . . . locate the society’s center and affirm its connection with transcendent things by stamping a territory with ritual signs of dominance. . . . When kings journey around the countryside . . . they mark it, like some wolf or tiger spreading his scent through his territory, as almost physically part of them.

But Chwe qualifies Geertz’s evocative metaphor. He suggests that the exercise of power is less about the the royal progress awing the peasants, than the peasants realizing that other peasants are seeing the same thing, and being publicly awed by it. It is not the tiger’s musk, so much as the knowledge that everyone is smelling the musk at the same time that is important.

Our interpretation focuses exactly on publicity, the common knowledge that ceremonies create, with each onlooker seeing that everyone else is looking too. Progresses are mainly a technical means of increasing the total audience, because only so many people can stand in one place; common knowledge is extended because each onlooker knows that others in the path of the progress have seen or will see the same thing. That the monarch moves is hence not crucial; mass pilgrimages or receiving lines, in which the audience moves instead, form common knowledge also. Under our interpretation, widespread ritual signs of dominance do not by their omnipresence evoke transcendence but are rather more like saturation advertising: when I see the extent of a vast advertising campaign, I know that other people must see the advertisements too. This is quite different from the wolf analogy, if taken seriously: a lone animal knows to stay away from another’s area by smelling the scent at a given place; no one perceives or infers the entire scent trail (for that matter, scents keep away rivals, whereas progresses are for “domestic” consumption).

Rituals often take place in consecrated places. British kings are crowned in Westminster Abbey. They also often take place at a particular time of the year (see churches and organized religion, passim). So it is not at all a stretch to see the Davos meeting as a ritual that is held in the same overcrowded place at much the same time every year. Like many rituals, its boredom and its ceremony go hand in hand. For many years, Davos’s most obvious social purpose was to reinforce the consensus about globalization, in predictable ceremonial language. Its very dullness and lack of surprise was a side effect of its power.

That was then; this is now. I don’t think that it is at all implausible to see Trump’s planned descent on Davos this year as a version of a royal progress (see Stacie Goddard and Abe Newman on “neo-royalism”). Swooping into Davos, and making the world’s business and political elite bend their knees, would have created collective knowledge that there was a new political order, with Trump reigning above it all.

Business elites would be broken and cowed into submission, through the methods that Adam describes. The Europeans would be forced to recognize their place, having contempt heaped on them, while being obliged to show their gratitude for whatever scraps the monarch deigned to throw onto the floor beneath the table. The “Board of Peace” - an alarmingly vaguely defined organization whose main purpose seems to be to exact fealty and tribute to Trump - would emerge as a replacement for the multilateral arrangements that Trump wants to sweep away. And all this would be broadcast to the world. Adam’s combination of stage, convening and acting would provide a means to shape the collective understanding of a global audience that Trump was now in charge.

That, of course, is not what happened. First, the Europeans were finally pushed to the point where they pushed back. As Belgium’s prime minister put it, “Living as a happy vassal is one thing, existing as a miserable slave is another.”** It was clear that the Europeans were finally becoming willing to retaliate against Trump. That in turn had consequences for business.

As Adam suggests, businesses are unwilling to visibly step up to oppose Trump one on one. But businesses are not only individual participants in the ceremony. They are also members of a vast and depersonalized audience, via the anonymizing mechanism of the market, and, as Chwe suggests, it is the collective understanding of the audience that is most important. Just as the ouija board allows individuals to express their desires without being held accountable to them (thanks to the ‘ideomotor effect’) so too, the invisible hand of the market moves the planchette of stock prices in ways that no particular business can be held accountable for. When stock markets fall, even at the prospect of trade conflict between Europe and the United States, politicians pay attention. “Market fundamentals” (a loaded and problematic term) provided a very different understanding of the shared consensus than the one Trump sought to impose.

Second, Carney’s speech laid out an entirely different understanding of what was happening, and what had gone before. In his words:

Let me be direct: We are in the midst of a rupture, not a transition. Over the past two decades, a series of crises in finance, health, energy and geopolitics have laid bare the risks of extreme global integration. But more recently, great powers have begun using economic integration as weapons. Tariffs as leverage. Financial infrastructure as coercion. Supply chains as vulnerabilities to be exploited.

A family member joked with me that “it sounded like he was reading straight from Underground Empire,” Abe’s and my book (please go buy ! ) on how the integrated global world economy was weaponized. And that’s true, sort-of! Also, it is a rhetorically beautiful and well executed speech, in a way that politicians’ speeches rarely are (ask James Fallows, who knows political speech crafting from the inside). Its bluntness is the product of hard work and artifice.

But from Chwe’s more immediate perspective, what is more important than the vision of the past and future is where Carney said it and how he framed it. If you are planning a grand coronation ceremony, which is supposed to create collective knowledge that you are in charge, what happens when someone stands up to express their dissent in forceful terms?

The answer is that collective knowledge turns into disagreement. By giving the speech at Davos, Carney disrupted the performance of ritual, turning the Trumpian exercise in building common knowledge into a moment of conflict over whose narrative ought prevail. Chwe again, this time clarifying where he agrees and disagrees with James Scott.

A public declaration creates “political electricity” … But Scott’s main explanation is the same as ours, that public declarations create common knowledge: “It is only when this hidden transcript is openly declared that subordinates can fully recognize the full extent to which their claims, their dreams, their anger is shared by other subordinates.” When Ricardo Lagos accused General Pinochet of torture and assassination on live national television, he said “more or less what thousands of Chilean citizens had been thinking and saying in safer circumstances for fifteen years”; the openness and publicity, not the content, of his speech, made it a “political shock wave.” “In a curious way something that everyone knows at some level has only a shadowy existence until that moment when it steps boldly onto the stage”

This is why Carney’s speech was so remarkably efficacious. He wasn’t telling people anything that they didn’t know as individuals. He was, instead, turning that private knowledge into a putative collective understanding that countered the alternative collective understanding that Trump wanted to impose upon the world.

This is very much the way that dissidents think about politics, as Scott’s description of Lagos’s action suggests. And Carney very explicitly quotes Václav Havel to highlight the urgency and importance of disrupting the ritual.

In 1978, the Czech dissident Václav Havel, later president, wrote an essay called The Power of the Powerless. And in it, he asked a simple question: How did the communist system sustain itself?

And his answer began with a greengrocer. Every morning, this shopkeeper places a sign in his window: “Workers of the world, unite!” He doesn’t believe it. No one does. But he places the sign anyway to avoid trouble, to signal compliance, to get along. And because every shopkeeper on every street does the same, the system persists.

Not through violence alone, but through the participation of ordinary people in rituals they privately know to be false.

Havel called this “living within a lie.” The system’s power comes not from its truth but from everyone’s willingness to perform as if it were true. And its fragility comes from the same source: when even one person stops performing — when the greengrocer removes his sign — the illusion begins to crack.

So this, I think, provides a good integrated explanation of what happened at Davos; at least, it is the best that I can come up with. We should think about Davos as a site and moment of ceremony, in the terms that Chwe lays out, which cements common knowledge about who is in charge, and what the principles of rule are. That, in turn provided Trump with a possible opportunity to anoint himself as the central figure in a new vision of the West, in which, in Stacie and Abe’s terms,

a small clique [maintains] dominance in both material and symbolic goods. It thus rejects notions of sovereign equality and noninterference, and rests instead on the idea that a royalist clique is dominant, and will only recognize rival “great cliques” as peers; all others are unequal, and not due recognition.

The ceremony was disrupted by European threats of retaliation, which in turn led the market audience to express its unhappiness, and by Carney’s quite deliberate and self-conscious effort to crack the illusion of inevitability.

That does not mean that the Trump political project has been defeated. It is going to be very hard for Europe and Carney to build a viable counter-consensus. Already, Trump is looking to discipline Canada and seize back control of the narrative. What we have seen was a battle, not a war. But to appreciate the weapons that the battle was fought with, and understand the prize that was contended for, it is really helpful to emphasize the relationship between ritual and collective expectations. Chwe’s book is the clearest account of this relationship that I know of.

* Non-rational choice sociologists may reasonably complain that they’ve been discussing this question for well over a century,. This is completely fair, but it is quite difficult for those who have not been initiated into the mysteries to read this work and understand why it is so important.

** “Happy vassal” has become a term of art in this debate.

Let's all decide not to live within the lie. If Trump can rename cabinet positions, so can we. The Department of Homeland Security is now the Department of Domestic Warfare. After all, he told us, "The enemy is within."

Was this an emperor's new clothes moment--i.e. where the commonly held version of reality is challenged, by being shown to be artificial, i.e. the product of common agreement?