Large Language Models are Uncanny

Like capitalism, LLMs are haunted: voids that seem to speak

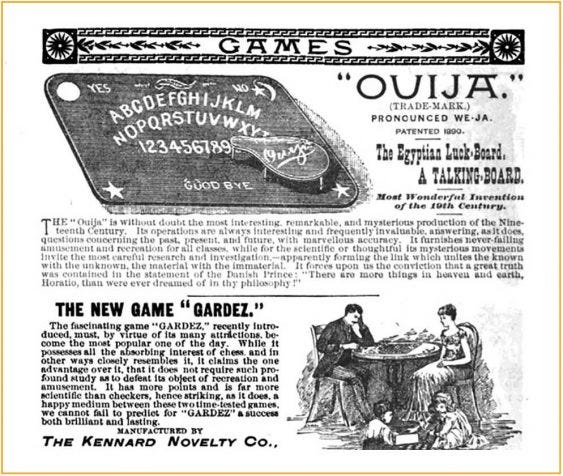

The week before last, I did an online lecture on Large Language Models and “Gopnikism” for Harvard’s Carr Center. If you want a 30 minute talk that summarizes the main themes of this newsletter, this is where you’ll find it. But there was one slide that didn’t quite fit. Its title, “Planchettes and Re-enchantment,” has very little to do with what I ended up talking about, because I had to remake the talk on the fly (I had less time than I had planned for). So why planchettes?

Because the spooky movement of a ouija board’s planchette is plausibly a useful metaphor for Large Language Models (LLMs). I’m guessing that most people know how a planchette works, but in case not, here’s a description I came across last week in Avram Davidson’s The Adventures of Doctor Eszterhazy (which was just re-released after decades of being out of print - an extraordinary collection of short stories).

The oui-ja board somewhat resembled an easel laid flat, on which had been painted the letters of the alphabet and the first ten numbers, plus a few other signs. On it rested a sort of wooden trivet with casters. “Now,” suggested Eszterhazy, “if several of us, perhaps three, will sit down and place the tips of the fingers lightly on top of the planchette so that no single one person will be able to move it without the two others being aware, it is said that the spirits may guide it to various letters and numbers … perhaps by this method spelling out a message.”

There are many low budget horror movies in which people try to contact the spirits of the dead through a ouija board. It usually doesn’t work out so well.

The reason why Hollywood keeps coming back to ouija boards as a source of scary malignity is that they are genuinely uncanny. If you’ve ever used a ouija board, you’ll know that the planchette does seem to have a life of its own, even though its motion is a collective side-effect of the motions of the people whose fingers lightly rest on top of it. As this Vox explainer says, it’s a product of the “ideomotor effect” - how the brain affects unconscious small movements - but it is also a product of the fact that several people are touching the planchette, so that no individual seems in control. The planchette doesn’t work if only one person is touching it.

This spooky-action-at-a-close-up evokes some of the reasons why LLMs can be creepy too. Many people don’t like LLM (or, strictly speaking, diffusion model - the LLM is usually an intermediary technology) art, and for many reasons, starting with its strong tendencies toward banality. It is difficult to prevent it from converging on one or another not particularly interesting attractor in art-space.

But some people go beyond dislike - they actually find that LLM-art makes them uneasy, to the point of mild horror or nausea. I would guess (maybe incorrectly) that many of those who react in this way find it uncanny for the same reasons that others or the same people are disturbed by the messages conveyed through a ouija board.

Which is to say: LLM art is not the product of any individual artist (even when it is prompted to copy an individual artist’s style, it tends to create a flavored composite of a broader genre). Like the ouija board, LLMs are a technology that transforms collective inputs - the enormous corpuses of words and human created content that they has been fed on - into apparently quite specific outputs that are not the intended creation of any conscious mind.

Hence, LLM art sometimes seems to communicate a message, as art does, but it is unclear where that message comes from, or what it means. If it has any meaning at all, it is a meaning that does not stem from organizing intention. To adapt someone else’s phrase, we can no longer speak of intelligence; only the products of its decay remain. It is unsurprising that many people find these products to be disturbing.

LLMs are eerie, then, in a specific and technical sense of that term. The late Mark Fisher wrote an influential book, where he distinguished between the “weird” and the “eerie.” He had an easier time pinning down the weird, because it has a longer tradition and current debate around it.* The weird is “that which does not belong,” encompassing both Lovecraftian horrors and natural phenomena like black holes.*

Compare this to a black hole: the bizarre ways in which it bends space and time are completely outside our common experience, and yet a black hole belongs to the natural-material cosmos — a cosmos which must therefore be much stranger than our ordinary experience can comprehend.

The eerie is harder to pin down.

A sense of the eerie seldom clings to enclosed and inhabited domestic spaces; we find the eerie more readily in landscapes partially emptied of the human. What happened to produce these ruins, this disappearance? What kind of entity was involved? What kind of thing was it that emitted such an eerie cry? As we can see from these examples, the eerie is fundamentally tied up with questions of agency. What kind of agent is acting here? Is there an agent at all?

This captures the specific uncanniness of LLMs and LLM art. LLM art is so disturbing because it is culture that has been drained of all direct intentionality. Just like the movements of the planchette, it is a by-product of collective agency, without itself being an agent. A void has been created, and something disturbing appears to have crept in.

The sensation of the eerie occurs either when there is something present where there should be nothing, or is there is nothing present when there should be something.

That is one of the sensations induced by looking at, or thinking about LLM generated art. Fisher died years before LLMs were a thing, but his writing anticipated their effect, and he likely would have found them fascinating. They fit remarkably aptly into his imagined set of categories.

In particular, I would guess that he’d have had a lot to say about the relationship between LLMs and capitalism.

Capital is at every level … eerie … : conjured out of nothing, capital nevertheless exerts more influence than any allegedly substantial entity.

If there is any common technical usage which is as eerie, when you look at it askance, as the “invisible hand,” I really don’t know what it is.

If LLM art has any long term significance (and it might, whether despite or because of its banality), I suspect that it will find it in exploiting this, and similar consonances. Because LLM art is a void that seems to speak, it may stand in for other vast social processes, like capitalism, that possess the same characteristics.

Ted Chiang has a lovely essay suggesting that AI is like McKinsey - an organizational form that allows people to evade responsibility in the name of “shareholder value.” That metaphor emphasizes how capitalism provides a blame-sump, or, in Daniel Davies’ terms, an “accountability sink,” for specific agents and people who want things to happen without those things being attributed to them.

But there is another perspective, from which capitalism is a system in which things happen - things that have the appearance of agency - without any real intentionality behind them. It is that facial appearance and the uncanny absence lurking behind the mask, which is shared by the movement of the planchette, the imitative virtuosity (and failures) of LLM art, and the intricate workings of markets at scale.

* It’s worth comparing Fisher’s examples to the content discussed in my last post. Fisher was a co-founder with Nick Land of the Cybernetic Culture Research Unit, and a friendly antagonist of Land’s who nonetheless remained firmly on the Marxist left. The repeated recurrence of key images - black holes and Lovecraftian entities - in these debates could be the result of coincidence, mutual influence, or strange attractors in popular culture, depending.

** I was a minor hanger-on in the New Weird discussions mentioned in this obituary piece on Fisher - I’m the “someone named Henry” who made the entirely banal point that is quoted here . To my intellectual misfortune, I didn’t know Fisher when he was alive, nor his broader writing (I had read this fantastic interview he did with the electronic music artist, Burial, but hadn’t realized there was a body of work behind it).

General relativity is weird. Quantum mechanics is eerie.

I'll also quote a tweet from Erkhyan Rafosa (@Erkhyan):

"It’s funny how recognizing AI nowadays is just the same old rules as recognizing the fae in old tales. 'Count the fingers, count the knuckles…'"

Do many artists actually claim explicit intention though? I'm thinking of D H Lawrence's "Not I but the wind that blows through me", but lots of other examples.

And vice versa, some early uses of "planchette" treated it as a proper noun, capitalised and given agency - Anthony Powell does this.