Why did Silicon Valley turn right?

The "pounded progressive ally" thesis has limits

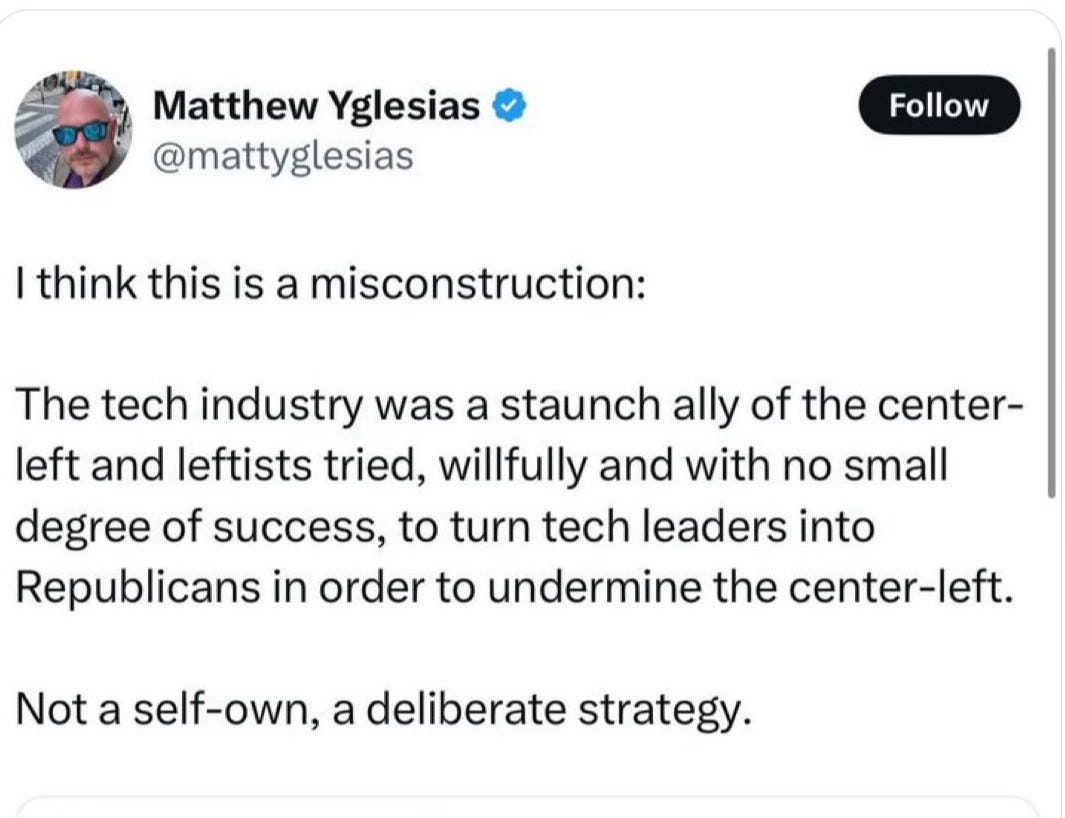

A significant chunk of the Silicon Valley tech industry has shifted to the right over the last few years. Why did this happen? Noah Smith and Matt Yglesias think they have the answer. Both have amplified the argument of a Marc Andreessen tweet, arguing that progressives are at fault, for alienating their “staunch progressive allies” in the tech industry.

Noah:

Matt on how this was all part of a “deliberate strategy” to “undermine the center-left.”

These are not convincing explanations. Years ago, Matt coined an extremely useful term, the “Pundit’s Fallacy,” for “the belief that what a politician needs to do to improve his or her political standing is do what the pundit wants substantively.” I worry that Noah and Matt risk falling into a closely related error. “The Poaster’s Mistake” is the belief that the people who make your online replies miserable are also the one great source of the misery of the world. Noah and Matt post a lot, and have notably difficult relations with online left/progressives. I can’t help but suspect that this colors their willingness to overlook the obvious problems in Andreessen’s “pounded progressive ally”* theory.

Succinctly, there were always important differences between Silicon Valley progressivism and the broader progressive movement (more on this below), Marc seems to have been as much alienated by center-left abundance folks like Jerusalem Demsas for calling him and his spouse on apparent NIMBYist hypocrisy as by actual leftists, and has furthermore dived into all sorts of theories that can’t be blamed on the left, for example, publicly embracing the story about an “illegal joint government-university-company censorship apparatus” which is going to be revealed real soon in a blizzard of subpoenas.

I suspect that Noah and Matt would see these problems more clearly if they weren’t themselves embroiled in related melodramas. And as it happens, I have an alternative theory about why the relationship between progressives and Silicon Valley has become so much more fraught, that I think is considerably better.

Better: but I certainly can’t make strong claims that this theory is right. Like most of what I write here, you should consider it to be social science inflected opinion journalism rather than Actual Social Science, which requires hard work, research and time. But I think it is the kind of explanation that you should be looking for, rather than ‘the lefties were plotting to undermine me and my allies,’ or, for that matter ‘this was completely inevitable, because Silicon Valley types were closeted Nazi-fanciers from the beginning.’ It’s clear that some change has, genuinely, happened in the relationship between Silicon Valley and progressives, but it probably isn’t going to be one that fits entirely with any particular just-so story. So here’s my alternative account - take pot-shots at it as you like!

********

Before the story comes the social science. The shifting relationship between the two involves- as far as I can see - ideas, interests and political coalitions. The best broad framework I know for talking about how these relate to each other is laid out in Mark Blyth’s book, Great Transformations: Economic Ideas and Institutional Change in the Twentieth Century.

Mark wants to know how big institutional transformations come about. How, for example, did we move from a world in which markets were fundamentally limited by institutional frameworks created by national governments, to one in which markets dominated and remade those frameworks?

Mark’s answer is that you cannot understand such ‘great transformations’ without understanding how ideas shape collective interests. Roughly speaking (I’m simplifying a lot), when institutional frameworks are stable, they provide people with a coherent understanding of what their interests are, who are their allies and who are their adversaries. But at some point, perhaps for exogenous reasons, the institutional order runs into a crisis, where all that seemed to be fixed and eternal suddenly becomes unstable. At that point, people’s interests too become malleable - they don’t know how to pursue these interests in a world where everything is up for grabs. Old coalitions can collapse and new ones emerge.

It is at this point that ideas play an important role. If you - an intellectual entrepreneur - have been waiting in the wings with a body of potentially applicable ideas, this is your moment! You leap forward, presenting your diagnosis both of what went wrong in the old order, and what can make things right going forward. And if your ideas take hold, they disclose new possibilities for political action, by giving various important actors a sense of where their interests lie. New coalitions can spring into being, as these actors identify shared interests on the basis of new ideas, while old coalitions suddenly look ridiculous and outdated. Such ideas are self-fulfilling prophecies, which do not just shape the future but our understanding of the past. A new institutional order may emerge, cemented by these new ideas.

As Mark puts it in more academic language:

Economic ideas therefore serve as the basis of political coalitions. They enable agents to overcome free-rider problems by specifying the ends of collective action. In moments of uncertainty and crisis, such coalitions attempt to establish specific configurations of distributionary institutions in a given state, in line with the economic ideas agents use to organize and give meaning to their collective endeavors. If successful, these institutions, once established, maintain and reconstitute the coalition over time by making possible and legitimating those distributive arrangements that enshrine and support its members. Seen in this way, economic ideas enable us to understand both the creation and maintenance of a stable institutionalized political coalition and the institutions that support it.

Thus, in Mark’s story, economists like Milton Friedman, George Stigler and Art Laffer played a crucial role in the transition from old style liberalism to neoliberalism. At the moment when the old institutional system was in crisis, and no-one knew quite what to do, they provided a diagnosis of what was wrong. Whether that diagnosis was correct in some universal sense is a question for God rather than ordinary mortals. The more immediate question is whether that diagnosis was influential: politically efficacious in justifying alternative policies, breaking up old political coalitions and conjuring new ones into being. As it turned out, it was.

********

So how does this explain recent tensions between progressives and Silicon Valley? My hypothesis is that we are living in the immediate aftermaths of two intertwined crises. One was a crisis in the U.S. political order - the death of the decades-long neoliberalism that Friedman and others helped usher in. The other was an intellectual crisis in Silicon Valley - the death of what Kevin Munger calls “the Palo Alto Consensus.” As long as neoliberalism shaped the U.S. Democratic party’s understanding of the world, and the Palo Alto Consensus shaped Silicon Valley’s worldview, soi-disant progressivism and Silicon Valley could get on well. When both cratered at more or less the same time, different ideas came into play, and different coalitions began to emerge among both Washington DC Democrats and Silicon Valley. These coalitions don’t have nearly as much in common as the previous coalitions did.

There are vast, tedious arguments over neoliberalism and the Democratic party, which I’m not going to get into. All I’ll say is that a left-inflected neoliberalism was indeed a cornerstone of the Democratic coalition after Carter, profoundly affecting the ways in which the U.S. regulated (or, across large swathes of policy, didn’t regulate) the Internet and e-commerce. 1990s Democrats were hostile to tech regulation: see Margaret O’Mara’s discussion of ‘Atari Democrats’ passim, or, less interesting, myself way back in 2003:

In 1997, the White House issued the “Framework for Global Electronic Commerce,” … drafted by a working group led by Ira Magaziner, the Clinton administration’s e-commerce policy “architect.” Magaziner … sought deliberately to keep government at the margins of e-commerce policy. His document succeeded, to a quite extraordinary extent, in setting the terms on which U.S. policymakers would address e-commerce, and in discouraging policymakers from seeking to tax or regulate it.

E-commerce transactions did, eventually, get taxed. But lots of other activities, including some that were extensively regulated in the real world, were lightly regulated online or not regulated at all, on the assumption that government regulation was clumsy and slow and would surely stifle the fast-adapting technological innovation that we needed to build the information superhighway to a glorious American future.

This happy complaisance certainly helped get the e-commerce boom get going, and ensured that when companies moved fast and broke things, as they regularly did, they were unlikely to get more than an ex post slap on the wrist. A consensus on antitrust that spanned Democrats and Republicans allowed search and e-commerce companies to build up enormous market power, while the 1996 Communications Decency Act’s Section 230 allowed platform companies great freedom to regulate online spaces without much external accountability as they emerged.

All this worked really well with the politics of Silicon Valley. It was much easier for Silicon Valley tech people to be ‘staunch allies’ in a world where Democratic politicians bought into neoliberalism and self-regulation. In February 2017, David Broockman, Greg Ferenstein and Neil Malhotra conducted the only survey I’m aware of on the political ideology of Silicon Valley tech elites. As Neil summarized the conclusions:

Our findings led us to greatly rethink what we think of as “the Silicon Valley ideology,” which many pundits equate with libertarianism. In fact, our survey found that over 75% of technology founders explicitly rejected libertarian ideology. Instead, we found that they exhibit a constellation of political beliefs unique among any population we studied. We call this ideology “liberal-tarianism.” Technology elites are liberal on almost all issues – including taxation and redistribution – but extremely conservative when it comes to government regulation, particularly of the labor market. Amazingly, their preferences toward regulation resemble Republican donors.

Broockman, Ferenstein and Malhotra found that this wasn’t simple industry self-interest. These elites were similarly hostile to government regulation of other sectors than technology. But they were far more fervently opposed to regulation than regular millionaires, and were notably hostile to unions and unionization, with large majorities saying that they would like to see private sector (76%) and public sector (72%) unions decline in influence. And just as Democrats influenced Silicon Valley, Silicon Valley influenced the Democrats, bringing the two even closer together.

These findings help explain why the technology industry was a core part of the Democratic coalition and why the Obama Administration was fairly lax when it came to the regulation of the technology industry. Silicon Valley worked from within the Democratic coalition to move regulatory policy to the right, while supporting the party’s positions on social issues, economic redistribution, and globalization. Perhaps it is not so surprising that the revolving door between the Obama Administration and Silicon Valley companies seemed to always spin people in or out.

It’s really important to note that Silicon Valley politics was not just about its attitudes to Washington but to the world, and to its own technological destiny. As Kevin Munger has argued, the official ideologies of big platform companies shared a common theme: their business models would connect the world together, to the betterment of humankind. As a remarkable internal memo written by Facebook VP, Andrew “Boz” Bosworth put it in 2016 ( reported by Ryan Mac, Charlie Warzel and Alex Kantrowitz) :

“We connect people. Period. That’s why all the work we do in growth is justified. All the questionable contact importing practices. All the subtle language that helps people stay searchable by friends. All of the work we do to bring more communication in. The work we will likely have to do in China some day. All of it” … “So we connect more people,” he wrote in another section of the memo. “That can be bad if they make it negative. Maybe it costs someone a life by exposing someone to bullies. “Maybe someone dies in a terrorist attack coordinated on our tools.”

That too influenced Washington DC: politicians like Hilary Clinton bought into this vision, delivering speeches and implementing policy around it. Journalism bought into it too, so that a thousand puff pieces on Silicon Valley leaders were inflated by Kara Swisher and her ilk, ascending majestically into the empyrean. And, most importantly of all, Silicon Valley itself bought into it. When Silicon Valley fought with the Obama administration, it was over the illiberal policies that threatened both its business model and the dream of a more liberal, globally connected world. After the Snowden revelations broke, Eric Schmidt famously worried that U.S. surveillance might destroy the Internet. But even then, the general assumption was that liberalism and technological innovation went hand in hand. The more liberal a society, the more innovative it would be, and the more innovation there was, the stronger that liberalism would become.

There was a small but significant right wing faction in Silicon Valley, centered around Peter Thiel and a couple of other members of the Paypal mafia. Weird reactionaries like Curtis Yarvin were able to find a niche, while Palantir, unlike pretty well all the other Silicon Valley software and platform companies, was willing to work with the U.S. military and surveillance state from the beginning. But the Silicon Valley culture, like the founders, tended liberaltarian.

It’s no surprise that relations between DC progressives and tech company elites were so friendly - the neoliberal consensus among Washington DC Democrats and the Palo Alto Consensus were highly compatible with each other. Both favored free markets and minimal regulation of technology, while sidelining unions, labor politics and too close an examination of the market power of the big tech companies. There were frictions of course - even neoliberal Democrats were often keener on regulation for many people in Silicon Valley - but Democrats could see themselves in Silicon Valley and vice versa without too much squinting.

********

If that has changed, it is not simply because progressives have moved away from Silicon Valley. It is because both the neoliberal consensus and the Palo Alto consensus have collapsed, leading the political economies of Washington DC and Silicon Valley to move in very different directions.

A lot of attention has been paid to the intellectual and political collapse of neoliberalism. This really got going thanks to Trump, but it transformed the organizing ideas of the Democratic coalition too. During the Trump era, card-carrying Clintonites like Jake Sullivan became convinced that old ideas about minimally regulated markets and trade didn’t make much sense any more. Domestically, they believed that the “China shock” had hollowed out America’s industrial heartland, opening the way for Trump style populism. Reviving U.S. manufacturing and construction might be facilitated through a “Green New Deal” that would both allow the U.S. to respond effectively to climate change, and revive the physical economy. Internationally, they believed that China was a direct threat to U.S. national security, as it caught up with the U.S. on technology, industrial capacity and ability to project military force. Finally, they believed that U.S. elites had become much too supine about economic power, allowing the U.S. economy to become dominated by powerful monopolies. New approaches to antitrust were needed to restrain platform companies which had gotten out of control. Unions would be Democrats’ most crucial ally in bringing back the working class.

Again, I’m not going to talk about the merits of this analysis (a topic for other posts), but the politics. Both Matt and Noah like the hawkish approach to China, but not much else. Matt in particular seems to blame a lot of what has gone wrong in the last four years on an anti-neoliberal popular front, stretching from Jake Sullivan to Jacobin and the random online dude who thinks the Beatles Are Neoliberalism.

What Matt and Noah fail to talk about is that the politics of Silicon Valley have also changed, for reasons that don’t have much to do with the left. Specifically, the Palo Alto Consensus collapsed at much the same time that the neoliberal consensus collapsed, for related but distinct reasons.

No-one now believes - or pretends to believe - that Silicon Valley is going to connect the world, ushering in an age of peace, harmony and likes across nations. That is in part because of shifting geopolitics, but it is also the product of practical learning. A decade ago, liberals, liberaltarians and straight libertarians could readily enthuse about “liberation technologies” and Twitter revolutions in which nimble pro-democracy dissidents would use the Internet to out-maneuver sluggish governments. Technological innovation and liberal freedoms seemed to go hand in hand.

Now they don’t. Authoritarian governments have turned out to be quite adept for the time being, not just at suppressing dissidence but at using these technologies for their own purposes. Platforms like Facebook have been used to mobilize ethnic violence around the world, with minimal pushback from the platform’s moderation systems, which were built on the cheap and not designed to deal with a complex world where people could foment horrible things in hundreds of languages. And there are now a lot of people who think that Silicon Valley platforms are bad for stability in places like the U.S. and Western Europe where democracy was supposed to be consolidated.

My surmise is that this shift in beliefs has undermined the core ideas that held the Silicon Valley coalition together. Specifically, it has broken the previously ‘obvious’ intimate relationship between innovation and liberalism.

I don’t see anyone arguing that Silicon Valley innovation is the best way of spreading liberal democratic awesome around the world any more, or for keeping it up and running at home. Instead, I see a variety of arguments for the unbridled benefits of innovation, regardless of its benefits for democratic liberalism. I see a lot of arguments that AI innovation in particular is about to propel us into an incredible new world of human possibilities, provided that it isn’t restrained by DEI, ESG and other such nonsense. Others (or the same people) argue that we need to innovate, innovate, innovate because we are caught in a technological arms race with China, and if we lose, we’re toast. Others (sotto or brutto voce; again, sometimes the same people) - contend innovation isn’t really possible in a world of democratic restraint, and we need new forms of corporate authoritarianism with a side helping of exit, to allow the kinds of advances we really need to transform the world.

I have no idea how deeply these ideas have penetrated into Silicon Valley - there isn’t a fully formed new coalition yet. There are clearly a bunch of prominent people who buy into these ideas, to some greater or lesser degree, including Andreessen himself. I’d assume that there are a lot of people in Silicon Valley who don’t buy into these arguments - but they don’t seem to have a coherent alternative set of ideas that they can build a different coalition around. And all this was beginning to get going before the Biden administration was mean to Elon Musk, and rudely declined to arrange meetings between Andreessen, Horowitz and the very top officials. Rob Reich recalls a meeting with a bunch of prominent people in the Valley about what an ideal society for innovation might look like. It was made clear to him that democracy was most certainly not among the desirable qualities.

So my bet is that any satisfactory account of the disengagement between East Coast Democrats and West Coast tech elites can’t begin and end with blaming the left. For sure, the organizing ideas of the Democrats have shifted. So too - and for largely independent reasons - have the organizing ideas of Silicon Valley tech founders. You need to pay attention to both to come up with plausible explanations.

I should be clear that this is a bet rather than a strong statement of How It Was. Even if my argument did turn out to be somewhat or mostly right in broad outline, there are lots of details that you would want to add to get a real sense of what had happened. Ideas spread through networks - and different people are more or less immune or receptive to these ideas for a variety of complicated social or personal reasons. You’d want to get some sense of how different networks work to flesh out the details.

And the whole story might be wrong or misleading! Again, this is based on a combination of political science arguments and broad empirical impressions, rather than actual research. But I would still think that this kind of account is more likely to be right, than the sort of arguments that Matt and Noah provide. Complicated politics rarely break down into easy stories of who to blame. Such stories, furthermore, tend to be terrible guides to politics in the future. We are still in a period of crisis, where the old coalitions have been discredited, and new coalitions haven’t fully cohered. Figuring out how to build coalitions requires us not to dwell on past hostilities but pay lively attention to future possibilities, including among people whom we may not particularly like.

* It’s impossible for me to read Andreessen’s tweet without imagining the Chuck Tingle remix. That’s almost certainly my fault, not his.

The history of the business culture of SV is pretty well-documented. A witches brew of academic/anarchistic/military/hobbyist cultures all bonding over the twin ideas of changing the world and making a lot of money. Nice to see a mention of the deliberately light touch of regulation in the early days of the World Wide Web, as they used to call it. Much like AI today, everyone agreed it was important but no one could say why, exactly, and SV got VERY comfortable with that approach. Its gradual phase-out alone explains a lot about the current political position of SV. Add in the galactic wealth and (literal) Galactic ambitions of characters like Andreesen, Theil, and Musk and you're just about there.

I remember when the biggest problem with SV billionaires was they were galactic assholes like Larry Ellison. Now they want to be the protagonist in a Heinlein juvenile, and if democracy has to go its a shame but the story and their egos demand it. But really, the black hole of all that wealth concentrated in the persons of a bunch of delusional narcissists being fed fantasies of power explains most of where SV is today. Add in SV betting the farm on AI, an insanely expensive technology with no profitable use model waiting to crash their (and our) entire economy, and you've got a bunch of desperate billionaires looking for a bailout. And then there's crypto. Among other things, the Trump presidency is going to be very, very expensive for the American people.

Respectfully, this seems like a lot of words to make the point that while the emphasis is put on progressive ideas with little economic impact (inclusion, diversity, representation). moneyed interest will play along and even take advantage of the PR, but as soon as progressive economic ideas are in play (labor rights, wealth redistribution, regulation) they will do a mercenary 180 and run to the reactionaries for help.

Also, I think Noah and Matt are just auditioning for Mark's attention, more than falling into any kind of fallacy.