Why China is going it alone on technology

When the US does things to other countries, they might possibly respond!

As I’ve said previously, this newsletter mostly presents social-science inflected opinion journalism - ideas and claims that (I hope!) are not obviously wrong, but that certainly haven’t been ground between the millstones of academic peer review. What’s below is different: presenting the results of some Real Actual Research (the good bits of which I am not really responsible for) and keeping most of the opinion till the end.

When Americans talk about the U.S.-China tech relationship these days, they tend to focus on China’s threat to America. And indeed, China is ruled by a notably nasty autocratic regime, with a long history of executions, human rights abuses and, most recently, genocide. This leads to a lot of analysis that depicts China as a constant and enduring threat, using technology to ease its long term path to global domination, while America sleeps. But could it be that many of China’s actions on technology are not about its long term threat to America, but America’s immediate threat to it?

That’s the motivating question of a brand new academic article that came out three days ago, which I was involved in. We - for values of we in which I am free-riding on colleagues - ask when countries are going to be willing to be technologically interdependent with other countries, and when they’ll prefer to go it alone. Interdependence means you can reap the benefit of other countries’ knowhow and products but that you risk them exploiting your dependence, while going it alone likely means worse tech, but also lower risk. Specifically, we want to know why China has become much more focused on technological independence as a goal. What we found was that China plausibly realized how vulnerable it was to one particular untrustworthy adversary: the United States of America.

To figure this out, we (again for values of ‘we’ that mean ‘my colleagues’) gathered a lot of textual data* from Chinese government sources. Many of the various organs of the Chinese government have their own newspapers. By tracing the conversations around science and technology across these newspapers, you can roughly track how different ideas about tech travel across the various parts of the Chinese state. More specifically, by using Natural Language Processing (NLP), we saw how key kinds of phrase, associated with particular ways of thinking about China’s technological risks, disseminated across the apparatus.

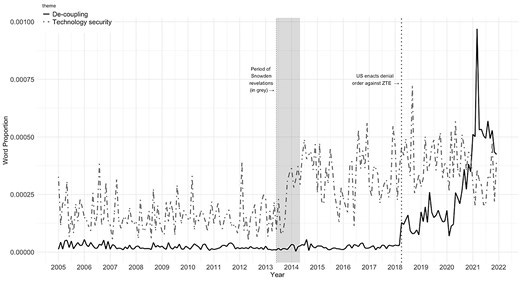

So what did we find? The data seem to tell a plausible story: the Chinese government really started to pay attention to technological risk at the two moments when it discovered what the U.S. could do and was doing. For example, take this graph showing changes in the frequency of two clusters of terms or ‘themes,’ associated with worries about technological dependence over the period from 2005 to 2022. The “technological security” theme includes the terms “information security,” “network security,” and “data sovereignty,” while “decoupling” contains the terms “chokepoint,” “self-reliance,” “indigenous research,” and “technological independence and strengthening.”

The results are pretty striking! Mentions of “technological security” related terms proceed at a steady-ish rate with some noise from 2005 till late 2013. Then, they suddenly become much more topical. Something similar - but more dramatic - happens to the frequency of phrases associated with “decoupling” in 2018.

So did anything happen in late 2013? Yes indeed, as we discuss in the article. In late 2013, the Snowden revelations started getting published, telling everyone how deeply the NSA had penetrated foreign information systems, including China’s, in pursuit of juicy information. And in 2018, the Trump administration suddenly and unexpectedly threatened to destroy the Chinese telecommunications manufacturer ZTE, by cutting off access to the US produced technologies that it needed to build its products. After the U.S. saw how successful this was, it adopted similar measures against Huawei and other Chinese firms.

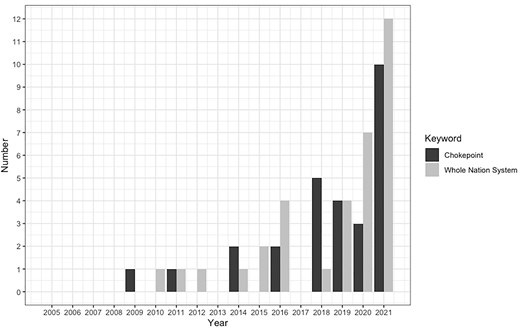

There’s other evidence that points in the same direction. If, for example, you graph language calling for China to move to a “whole-of-nation system” in order to counteract chokepoints and the like, you again see a sudden shift from 2018 onwards.

This is correlation, not causation. It is certainly possible that these patterns were caused by something else (though in the paper we explain why one possible alternative explanation, based on Xi’s accession to power and changes to policy, is not convincing). And there are certainly many factors that shape official language. But the most obvious explanation is that these shifts in language is driven by two sudden unexpected shocks. First, the Chinese government collectively realizes how powerful U.S. surveillance is in 2013. Second, it realizes how vulnerable it is to America’s exploitation of technological chokepoints against it in 2018.

So does this affect Chinese policy? Again, there is plausible correlational evidence that it does. If we look at official party, legislative or executive documents that use the term “network security,” we see a dramatic shift after 2013.

So too for the terms “chokepoint” and “whole-of-nation system” after 2018.

This sense of a change in thinking is confirmed if you actually _read_ the documents.

So what does this tell us about China? It highlights something that ought be obvious in American debate, but isn’t actually, for whatever reason. Chinese beliefs about the world and policies aren’t a constant. Just as Americans change their beliefs about China, sometimes because of how China behaves, Chinese officials change their beliefs about the U.S. We aren’t able to see what the timeline would have looked like, say, in a world where the U.S. had not gone after ZTE and Huawei. Perhaps it would have eventually converged, more or less, on something like the timeline of the world we are in. Perhaps it would have ended up somewhere wildly different, for better or for worse. But in the short term, and very possibly the longer term too, the revelation of American actions and intentions plausibly made China much more willing to go it alone.

The implications for how we should think about U.S. tariff policy, and its consequences for Chinese thinking, are left as an exercise for the reader.

* After the article was published, we noted that a small error had crept in: where the article says that we analyzed more than half a million newspaper articles on science and technology, we in fact analyzed slightly less.

Appreciate your article. Knowing that the US has propaganda aimed at discrediting China, the opposite is probably true. China has many technological and social advances that way exceed the US. The current human rights violations are becoming horrific in our country. The media is tainted with political propaganda. Half the country thinks all of this is good as long as we disenfranchise women, people of color, and lgbtq populations. The idea that we are somehow morally better is a complete lie.

There's also the cultural aspect. It's been argued that China is a civilisation state (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Civilization_state) and not expansionary expire (cf manifest destiny). As such the Great Firewall makes sense as a cultural firebreak ... Google was permitted to operate but they refused to apply for a media content license (with restrictions https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/googles-license-renewal-in-china-victory-defeat-or-stalemate/).

Another comparison might be privacy (EU's GDPR) or attitude towards copyright (cf moral rights https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moral_rights). Because these are not respected by SV who need to ingest massive cultural artifacts to train AI, they are interpreted as trade "barriers" rather than standards of dignity.Technology might have made the world flatter but doesn't close value gaps.