Vernor Vinge died some weeks ago. He wrote two very good science fiction novels, A Fire Upon the Deep and A Deepness in the Sky (the other books vary imo from ‘just fine’ to ‘yikes!’), but he will most likely be remembered for his arguments about the Singularity. I’ve written (Economist; unpaywalled version) about how both sides of the dominant Silicon Valley disputes about “AI” can be traced back to Vinge’s seminal essay. Do you think that uncontrollable AI will accidentally or deliberately squash human civilization as it reaches for the stars? Or instead believe that AI-augmented humanity will flourish and spread out through the cosmos? You have chosen the one tine, or the other, of Vinge’s Fork.

Over the last several months – since before Vinge died – I’ve been trying to puzzle out an argument. Here’s my best stab at it so far.

Vinge’s Fork is just one overdramatic rendering of a basic problem of modernity. The more fundamental intellectual dilemma begins to emerge at least a few centuries before. Understanding this prior fork helps us to understand the dueling metaphorical systems of the dominant AI debate right now. And more importantly: it helps us to understand what these metaphors obscure.

So what is this more fundamental fork within Vinge’s fork, like Benoit Blanc’s doughnut hole lurking inside the doughnut hole? One of the two tines is a particular reading of Renaissance humanism. I’ve always loved how John Crowley described Giambattista Vico’s ideas in his novel, The Solitudes.

history is made by man. Old Vico said that man can only fully understand what he has made; the corollary to that is, that what man has made he can understand: it will not, like the physical world, remain impervious to his desire to understand. So if we look at history and find in it huge stories, plots identical to the plots of myth and legend, populated by actual persons who however bear the symbols and even the names of gods and demons, we need be no more alarmed and suspicious than we would be on picking up a hammer, and finding its grip fit for our hand, and its head balanced for our striking. We are understanding what we have made, and its shape is ours; we have made history, we have made its street corners and the five-dollar bills we find on them; the laws that govern it are not the laws of nature, but they are the laws that govern us.

The other emerges sharply a few centuries later with Franz Kafka (channeled through Randall Jarrell)

[Kafka’s] world is the world of late capitalism, in which individualism has changed from the mixed but sought blessing of the romantics, to everybody's initial plight: the hero's problem is not to escape from society but to find it, to get any satisfactory place in it or relation to it. How shall a unit of labor-power be saved? The hero - anomalous term - struggles against mechanisms too gigantic, too endlessly and irrationally complex even to be understood, much less conquered … Dante tells you why you are damned (or saved, if we want to consider the jack-pot), and supplies the details of the whole mechanism; Kafka says that you are damned and can never know why - that the system of your damnation, like those of your society and your universe, is simply beyond your understanding; and he too gives the details of the system, and your confusion grows richer with each detail.

Vico-via-Crowley and Kafka-via-Jarrell present the two prongs of a vaster dilemma. Over the last few centuries, human beings have created a complex world of vast interlocking social and technological mechanisms. Can they grasp the totality of what they have created? Or alternatively, are they fated to subsist in the toils of great machineries that they have collectively created but that they cannot understand?

This, as Jarrell suggests, touches on the most fundamental anxieties of late capitalism. Understood in this light, current debates about the Singularity are so many footnotes to the enormous volumes of perplexity generated by the Industrial Revolution: the new powers that this centuries long transformation has given rise to, and the seething convolutions that those powers generate in their wake.

What “AI” does is to accentuate this dilemma. It makes it nearly impossible to ignore the fact that humans have created a world that is impervious to their understanding. The systems of that world cannot, any more, be separated from our lives. They live on our screens and in our pockets.

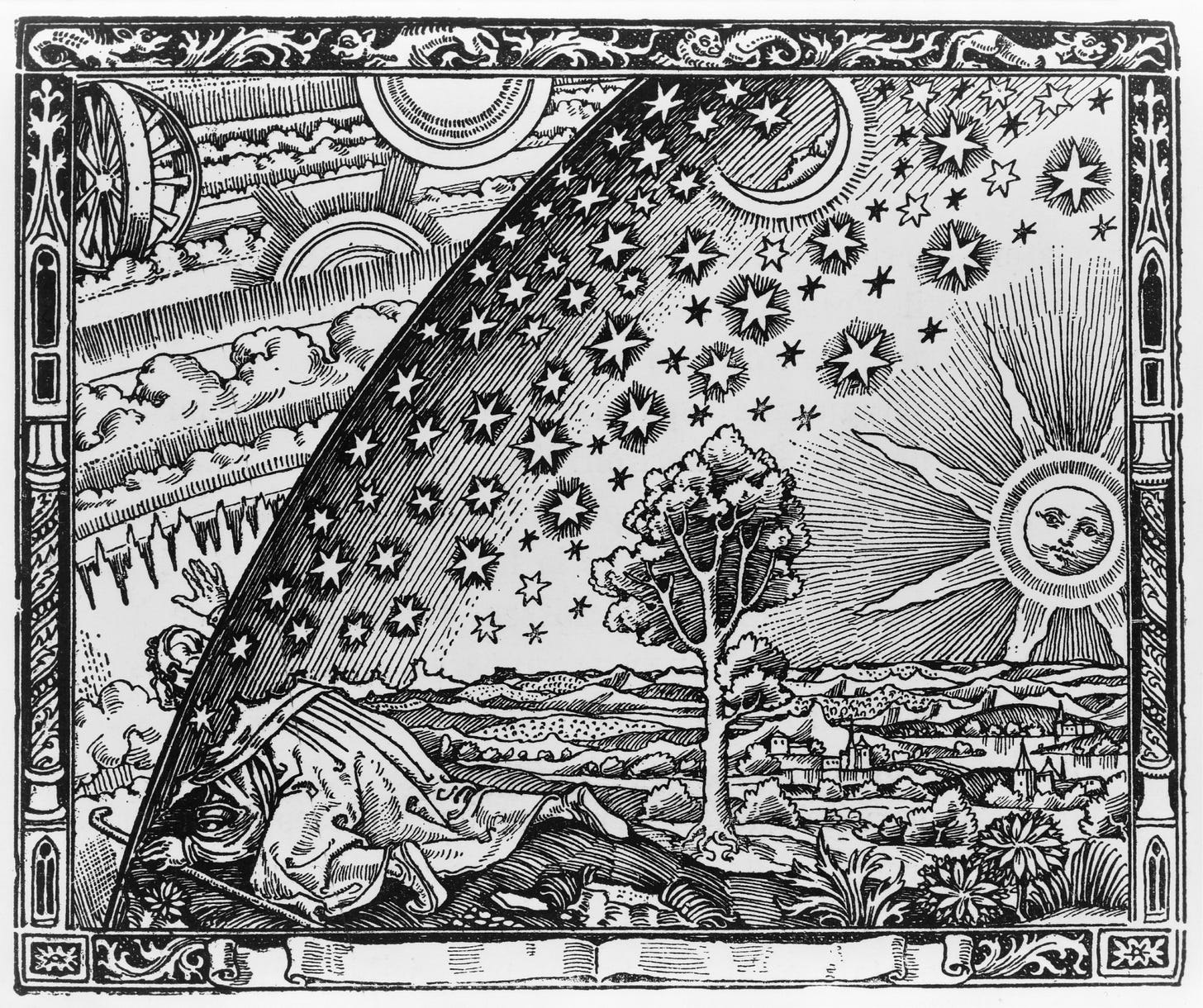

As with the obdurate physical universe, our first instinct is to populate this incomprehensible new world with gods and demons. We want to understand what we have made, and we impose the assumption that it will be populated by creatures with wills and desires like our own, whether they be dark powers or divinities.

Ezra Klein captures this instinct, suggesting that AI rationalism is a gussied up exercise in angelology, the kind of risky melange of white and black magic that John Dee or Giordano Bruno would have understood perfectly well:

I've come to believe that the correct metaphors [for AI] are in fantasy novels and occult texts. My colleague Ross Douthat had a good column on this. We talked about it as an act of summoning. The coders casting what are basically literally spells, right? They're strings of letters and numbers that if uttered or executed in the right order, create some kind of entity. They have no idea what will stumble through the portal. And what's oddest in my conversations with them is that they speak of this completely freely. They're not naive in the sense that they believe their call can be heard only by angels. They believe they might summon demons and they're calling anyway.

AI rationalists – like so many Renaissance magicians (or, for that matter, medieval Thomist philosophers) – start from a kind of humanistic superstition: the assumption that the purportedly superhuman entities they wish to understand and manipulate are intelligent, reasoning beings. We want to understand what we have made, and believe its shape is ours.

This, then, allows rationalists to delimit the possibilities of what these creatures might or might not do. Whether gods or monsters, they may possess vast powers – but they will also, as humans do, reason their way towards comprehensible goals. This might – if you are an optimistic rationalist – allow you to trammel these entities, through the subtle grammaries of game theory and Bayesian reasoning. Not only may you call spirits from the vasty deep, but you may entrap them in equilibria where they must do what you demand they do. As Crowley remarks elsewhere in The Solitudes, daemons are very literal minded creatures. Or – if you are a pessimistic rationalist –you may find yourself entrapped in an equilibrium where merely to know of its existence is to damn yourself to a choice between lifelong servitude or eternal hell. Either way, you at least have the consolation of knowing that you are in a world that is comprehensible to human understanding and perhaps even subject to human control.

But there is another, very different understanding of what might stumble through the portal. In a 1975 Galaxy essay,* another science fiction writer, Jerry Pournelle, describes attending a Stephen Hawking lecture. It described the radical uncertainty that would be unleashed by a different kind of singularity – the one that lurks at the heart of a black hole, if it were ever disentangled from the gnarly knot of space-time that surrounds it. In Pournelle’s interpretation:

it was an afternoon of Lovecraftian horror. Larry [Niven] and I escaped with our sanity, after first, in the question period, making certain that Hawking really did say what we thought he’d said. … causality is a local phenomenon of purely temporary nature; … that Cthulthu [sic] might emerge from a singularity, and indeed is as probable as, say, H. P. Lovecraft … Our rational universe is crumbling. Western civilization assumes reason; that some things are impossible, that’s all, and we can know that; … that the universe is at least in principle discoverable by human reason, is knowable. As we drove away from Pasadena, Larry remarked that if we ever had proximity to a singularity, he could well imagine people praying to it.

Pournelle’s essay suggests a world in which the dark possibilities that spill forth from the portal are not amenable to human reason, but radically undermine it.

Pournelle was an admirer of fascism: he and Niven wrote a version of Dante’s Inferno in which Benito Mussolini serves as Virgil and is redeemed. His notion of the singularity as a Lovecraftian portal of unreason in a fundamentally unknowable universe prefigures that of another reactionary: Nick Land, the ambiguous prophet of the Dark Enlightenment and neo-reactionary thought (NRx). For Land, the Lovecraftian monstrosities tumbling from the Singularity are markets, technology, capitalism.

If there is a good account of the weird love-hate relationship between rationalism and NRx, I haven’t read it, but the basic motivating impulse of NRx, as I understand it, is this. We are confronted by a world of rapid change that will not only defy our efforts to understand it: it will utterly shatter them. And we might as well embrace this, since it is coming, whether we want it to or not. At long last, the stars are right, and dark gods are walking backwards from the forthcoming Singularity to remake the past in their image. In one of Land’s best known and weirdest quotes:

Machinic desire can seem a little inhuman, as it rips up political cultures, deletes traditions, dissolves subjectivities, and hacks through security apparatuses, tracking a soulless tropism to zero control. This is because what appears to humanity as the history of capitalism is an invasion from the future by an artificial intelligent space that must assemble itself entirely from its enemy’s resources. Digitocommodification is the index of a cyberpositively escalating technovirus, of the planetary technocapital singularity: a self-organizing insidious traumatism, virtually guiding the entire biological desiring-complex towards post-carbon replicator usurpation

And this “technocapital singularity” is to be celebrated! William Gibson describes a future “like a deranged experiment in social Darwinism, designed by a bored researcher who kept one thumb permanently on the fast-forward button.” Land has turned this vision into a secular religion, in which Kafka’s gigantic and impossibly complex mechanisms, which tear the world apart and remake it in their image, are the worthy objects of our adoration.

Land’s “technocapital singularity” gives birth to “effective accelerationism.” And effective accelerationism, in turn, becomes the key intellectual driving force behind Marc Andreessen’s gospel of “techno optimism” which smoothes the delirious, ecstatic wildness of Land’s vision into a blended pap, more readily digestible by the broader public. But the strangeness still lurks in the heart of the thing. Software is going to eat the world, and It Will Be Awesome.

So these are the two dominant strains of metaphor that are being used to describe the complex, messy world that is coming into being. And each goes back a ways. Our imagined future is only superficially the future that Vinge made. Behind it lies the long aftermath of Vico’s Singularity, the moment in which it became clear that we were all the subjects of forces vaster than ourselves, and far less readily comprehended.

On one side, rationalism is a systematized, secularized version of the old hope that what human beings have made they can understand, and that the systems of the world, since they are our children, will be like us. Just as in the Renaissance, conjurers and mountebanks concoct strange hybrids of rationalism and magic. It isn’t just Ezra who describes this with grimoires and alchemy, angels and demons: such descriptive terms are half-ubiquitous, and for good reason. Thanks to popular culture, the images of the Renaissance mage and his ambitions are those that seem most apt when we grasp for way to describe strange complex forces that appear volitional and might do extraordinary things.

On the other, effective accelerationism is a celebration of the inhumanity and irrationalism of the forces that we have unleashed, a kind of shadow cybernetics that deprecates homeostasis and argues we should let positive feedback rip. It is only a few short steps from the religion of progress to the worship of dark gods – immanentizing the eschatonic hybrid of Lovecraft, Hayek and Deleuze that compose the “technocapital singularity.”

Some understanding of these metaphoric systems, and their history, is extremely useful in decoding the existing debate. Or at least, I’ve found it so. And it is arguably even more useful to understanding the possibilities that both these metaphors obscure.

Specifically – my own bet is that both are wildly misleading. The forces that we are conjuring up are not volitional, nor likely to be any time soon. They are not, in any plausible sense, conscious. But nor are they avatars of the unthinking chaos at the heart of the universe. We will not ever fully understand them, but we do not fully understand markets, bureaucracies, democracies or the other complex systems that we have created over the last couple of centuries. We live among them, we try to moderate them, and we set one against the other to create some room in which we can live our lives.

Doing this well is the worthy aim of policy - but it is very hard to keep to that aim through the circus and confusion of gaudy imagined futures. To dispel bad metaphors, we need good ones: not just systems of thinking but concrete images that are as powerful as the images of angels and magicians and of vast, unthinking inimical forces, but that conduct debate in more useful directions. How can we make the forces that we confront graspable, without either anthropomorphizing them or making them seem inevitable? It’s a hard problem, and not one I have any immediate solutions for.

Nice essay! I've always been frustrated that Vinge's conceptualization of the Singularity was so rarely linked to what I saw as one of its major implied reference points, which is the emergence of modern subjectivity, particularly in the way that Foucauldian analyses approached "epistemic" rupture. Foucault himself never managed (imho) to do a great job of actually exploring what kinds of selfhood or subjectivity people might have had before modernity, perhaps because modern epistemic frames overwhelm or infuse any such project. But I do think Foucault-inspired analyses were somewhat convincing that there *was* a rupture of some kind--that a person living before madness, before sexuality, before the prison, etc. would struggle to understand in a fundamental way what a modern self thought, did, felt and saw. (And thus also in the other direction.) Which is what I understood Vinge to be reaching for--that we were on the cusp of the emergence of a subjectivity that would be so radically different in some of its basic nature that there would be no communicating across that epistemic rupture, and that we couldn't really imagine on this side of it what it was going to be like on that side of it. The readings of the Singularity as "nerd rapture" or just as an enhancement/degradation of modern subjectivity missed the point, or perhaps just dragged it somewhere far afield from what he had in mind.

There was a viral interview some months back with a small IT business owner in Maine on his support of Trump. When the interviewer asked if he was concerned about the chaos a Trump victory might bring, he replied "that's why I'm voting for Trump". An awful lot of people hate and fear the modern world in general and are comfortable with the idea of tearing it down and starting over (in theory, because no one in favor of this wants to think through the aftermath, other than Steve Bannon). The fear of AI is driven more by this than any threat of daemons. Not even the people building the current interactions of "AI" fully understand it, let alone what it will do to society (beyond granting them wealth and power, somehow). But I fully agree that we need some sort of pataphysical language to grapple with a coming wave no one understands.