Vico's Singularity [republished]

AI, Renaissance wizardry and dark inhuman forces

This newsletter has been out of commission for the last couple of weeks, while I have been doing Other Writing (which will be appearing over time). One of the pieces that has come out is my review of Adam Becker’s great new book on tech thinking, More Everything Forever. The beginning below:

Adam Becker’s “More Everything Forever” begins by describing the ideas of Eliezer Yudkowsky, an AI guru who Sam Altman thinks deserves a Nobel Prize. Yudkowsky’s ambitions for humanity include “[p]erfect health, immortality,” and a future in which “[i]f you imagine something that’s worse than mansions with robotic servants for everyone, you are not being ambitious enough.” According to Yudkowsky and his peers, a “glorious transhumanist future” awaits us if we get AI right, although we face extinction if we get it wrong.

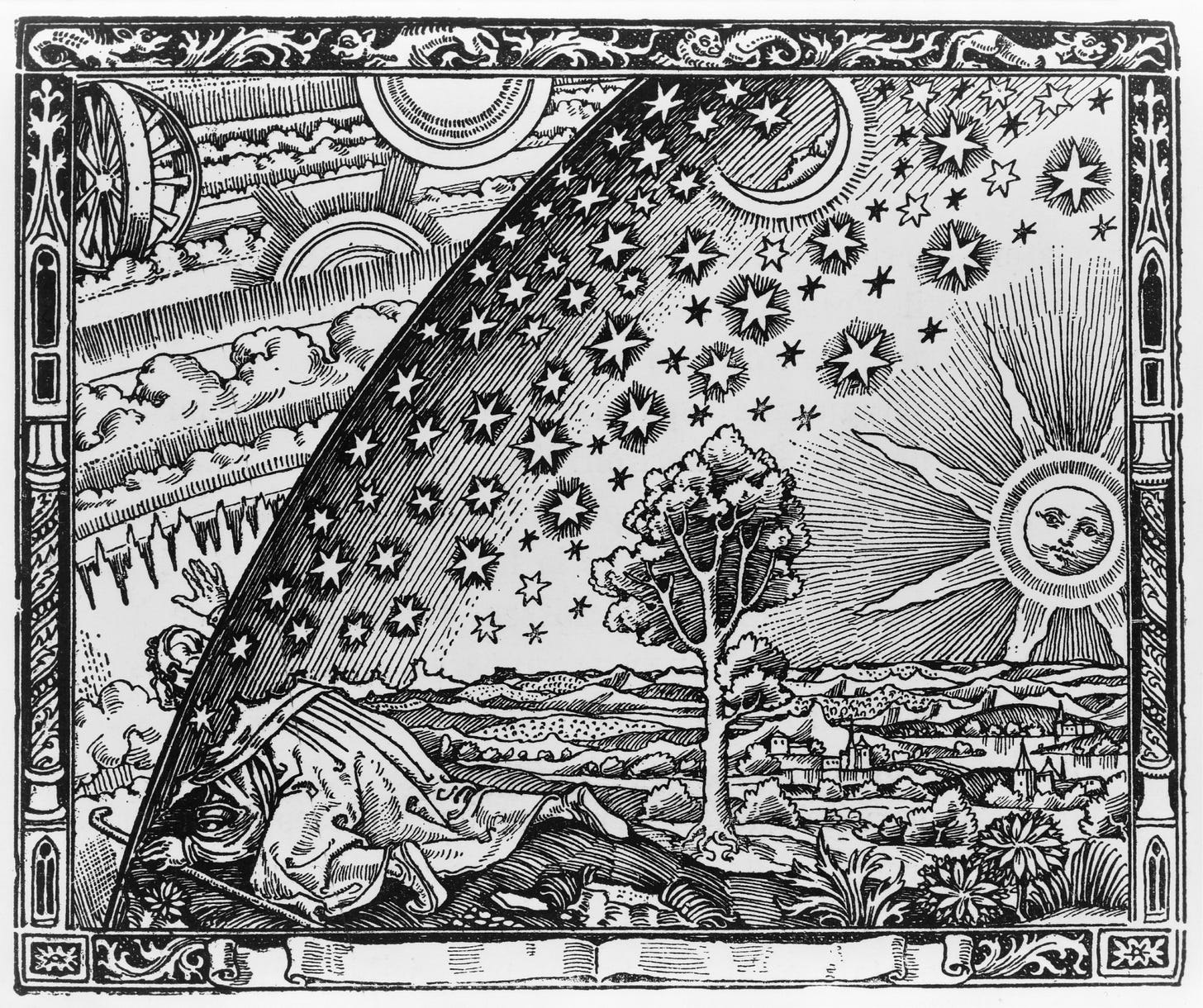

“AI” and “transhumanist” are new terms for rather older ambitions. As the seedy occultist Dr. Trelawney remarks in Anthony Powell’s 1962 novel, “The Kindly Ones,” “[t]o be forever rich, forever young, never to die … Such was in every age the dream of the alchemist.” Renaissance alchemists won the support of monarchs like Rudolf II, the Holy Roman Emperor who squandered his realm’s money on a futile quest to discover the Philosopher’s Stone. Now, as Becker explains, AGI, or artificial general intelligence, has become the means through which philosophers might transubstantiate our mundane reality into a realm in which the apparently impossible becomes possible: living forever, raising the dead, and remaking the universe in the shape of humanity.

Two confessions are in order. First, this is not the review I had planned to write. Becker’s own argument grounds the weirder philosophies of AI and other technology in a particular kind of science fiction. And when it comes to direct influence, he’s clearly right. I will have more to say about that next week. But while I was writing the review, I was reading (or: more accurately, listening to) the second chunk of Anthony Powell’s Dance to the Music of Time sequence. The consonance between the quote from Dr. Trelawney and Yudkowsky’s ambitions seemed too perfect not to be exploited. I often use such accidental consonances in my writing - they provide useful jolts of randomness to spur creativity.

Second, the review is a thinly disguised love letter to the writing of John Crowley. Crowley is one of the great unrecognized novelists of our time, and his Aegypt novel sequence seems exactly on point for the strange days we live in. It uses the techniques of fantasy and metafiction to draw parallels between Renaissance wizardry and the prevalent feeling half a century ago that the world was quivering on the cusp between the return of chaos and some great and universal transformation. It’s not his best book (that would be the incomparable Little, Big), but it is still extraordinary (especially the first two volumes) and is manifestly on topic. Hence, the Becker essay is a quite deliberate riff on Crowley, applying the Aegypt technique to current arguments about the transformative consequences of AI. I don’t think you need to know this or know Crowley to get the argument, but if you do, there are resonances.

And in lieu of a proper new post (again: more next week) below is an older one, from when I had many fewer readers than I have now, which lays out the longer argument behind the parallel to Renaissance magic. And if you want to read the review essay, again, it is here.

*************

Vernor Vinge died some weeks ago. He wrote two very good science fiction novels, A Fire Upon the Deep and A Deepness in the Sky (the other books vary imo from ‘just fine’ to ‘yikes!’), but he will most likely be remembered for his arguments about the Singularity. I’ve written (Economist; unpaywalled version) about how both sides of the dominant Silicon Valley disputes about “AI” can be traced back to Vinge’s seminal essay. Do you think that uncontrollable AI will accidentally or deliberately squash human civilization as it reaches for the stars? Or instead believe that AI-augmented humanity will flourish and spread out through the cosmos? You have chosen the one tine, or the other, of Vinge’s Fork.

Over the last several months – since before Vinge died – I’ve been trying to puzzle out an argument. Here’s my best stab at it so far.

Vinge’s Fork is just one overdramatic rendering of a basic problem of modernity. The more fundamental intellectual dilemma begins to emerge at least a few centuries before. Understanding this prior fork helps us to understand the dueling metaphorical systems of the dominant AI debate right now. And more importantly: it helps us to understand what these metaphors obscure.

So what is this more fundamental fork within Vinge’s fork, like Benoit Blanc’s doughnut hole lurking inside the doughnut hole? One of the two tines is a particular reading of Renaissance humanism. I’ve always loved how John Crowley described Giambattista Vico’s ideas in his novel, The Solitudes.

history is made by man. Old Vico said that man can only fully understand what he has made; the corollary to that is, that what man has made he can understand: it will not, like the physical world, remain impervious to his desire to understand. So if we look at history and find in it huge stories, plots identical to the plots of myth and legend, populated by actual persons who however bear the symbols and even the names of gods and demons, we need be no more alarmed and suspicious than we would be on picking up a hammer, and finding its grip fit for our hand, and its head balanced for our striking. We are understanding what we have made, and its shape is ours; we have made history, we have made its street corners and the five-dollar bills we find on them; the laws that govern it are not the laws of nature, but they are the laws that govern us.

The other emerges sharply a few centuries later with Franz Kafka (channeled through Randall Jarrell)

[Kafka’s] world is the world of late capitalism, in which individualism has changed from the mixed but sought blessing of the romantics, to everybody's initial plight: the hero's problem is not to escape from society but to find it, to get any satisfactory place in it or relation to it. How shall a unit of labor-power be saved? The hero - anomalous term - struggles against mechanisms too gigantic, too endlessly and irrationally complex even to be understood, much less conquered … Dante tells you why you are damned (or saved, if we want to consider the jack-pot), and supplies the details of the whole mechanism; Kafka says that you are damned and can never know why - that the system of your damnation, like those of your society and your universe, is simply beyond your understanding; and he too gives the details of the system, and your confusion grows richer with each detail.

Vico-via-Crowley and Kafka-via-Jarrell present the two prongs of a vaster dilemma. Over the last few centuries, human beings have created a complex world of vast interlocking social and technological mechanisms. Can they grasp the totality of what they have created? Or alternatively, are they fated to subsist in the toils of great machineries that they have collectively created but that they cannot understand?

This, as Jarrell suggests, touches on the most fundamental anxieties of late capitalism. Understood in this light, current debates about the Singularity are so many footnotes to the enormous volumes of perplexity generated by the Industrial Revolution: the new powers that this centuries long transformation has given rise to, and the seething convolutions that those powers generate in their wake.

What “AI” does is to accentuate this dilemma. It makes it nearly impossible to ignore the fact that humans have created a world that is impervious to their understanding. The systems of that world cannot, any more, be separated from our lives. They live on our screens and in our pockets.

As with the obdurate physical universe, our first instinct is to populate this incomprehensible new world with gods and demons. We want to understand what we have made, and we impose the assumption that it will be populated by creatures with wills and desires like our own, whether they be dark powers or divinities.

Ezra Klein captures this instinct, suggesting that AI rationalism is a gussied up exercise in angelology, the kind of risky melange of white and black magic that John Dee or Giordano Bruno would have understood perfectly well:

I've come to believe that the correct metaphors [for AI] are in fantasy novels and occult texts. My colleague Ross Douthat had a good column on this. We talked about it as an act of summoning. The coders casting what are basically literally spells, right? They're strings of letters and numbers that if uttered or executed in the right order, create some kind of entity. They have no idea what will stumble through the portal. And what's oddest in my conversations with them is that they speak of this completely freely. They're not naive in the sense that they believe their call can be heard only by angels. They believe they might summon demons and they're calling anyway.

AI rationalists – like so many Renaissance magicians (or, for that matter, medieval Thomist philosophers) – start from a kind of humanistic superstition: the assumption that the purportedly superhuman entities they wish to understand and manipulate are intelligent, reasoning beings. We want to understand what we have made, and believe its shape is ours.

This, then, allows rationalists to delimit the possibilities of what these creatures might or might not do. Whether gods or monsters, they may possess vast powers – but they will also, as humans do, reason their way towards comprehensible goals. This might – if you are an optimistic rationalist – allow you to trammel these entities, through the subtle grammaries of game theory and Bayesian reasoning. Not only may you call spirits from the vasty deep, but you may entrap them in equilibria where they must do what you demand they do. As Crowley remarks elsewhere in The Solitudes, daemons are very literal minded creatures. Or – if you are a pessimistic rationalist –you may find yourself entrapped in an equilibrium where merely to know of its existence is to damn yourself to a choice between lifelong servitude or eternal hell. Either way, you at least have the consolation of knowing that you are in a world that is comprehensible to human understanding and perhaps even subject to human control.

But there is another, very different understanding of what might stumble through the portal. In a 1975 Galaxy essay,* another science fiction writer, Jerry Pournelle, describes attending a Stephen Hawking lecture. It described the radical uncertainty that would be unleashed by a different kind of singularity – the one that lurks at the heart of a black hole, if it were ever disentangled from the gnarly knot of space-time that surrounds it. In Pournelle’s interpretation:

it was an afternoon of Lovecraftian horror. Larry [Niven] and I escaped with our sanity, after first, in the question period, making certain that Hawking really did say what we thought he’d said. … causality is a local phenomenon of purely temporary nature; … that Cthulthu [sic] might emerge from a singularity, and indeed is as probable as, say, H. P. Lovecraft … Our rational universe is crumbling. Western civilization assumes reason; that some things are impossible, that’s all, and we can know that; … that the universe is at least in principle discoverable by human reason, is knowable. As we drove away from Pasadena, Larry remarked that if we ever had proximity to a singularity, he could well imagine people praying to it.

Pournelle’s essay suggests a world in which the dark possibilities that spill forth from the portal are not amenable to human reason, but radically undermine it.

Pournelle was an admirer of fascism: he and Niven wrote a version of Dante’s Inferno in which Benito Mussolini serves as Virgil and is redeemed. His notion of the singularity as a Lovecraftian portal of unreason in a fundamentally unknowable universe prefigures that of another reactionary: Nick Land, the ambiguous prophet of the Dark Enlightenment and neo-reactionary thought (NRx). For Land, the Lovecraftian monstrosities tumbling from the Singularity are markets, technology, capitalism.

If there is a good account of the weird love-hate relationship between rationalism and NRx, I haven’t read it, but the basic motivating impulse of NRx, as I understand it, is this. We are confronted by a world of rapid change that will not only defy our efforts to understand it: it will utterly shatter them. And we might as well embrace this, since it is coming, whether we want it to or not. At long last, the stars are right, and dark gods are walking backwards from the forthcoming Singularity to remake the past in their image. In one of Land’s best known and weirdest quotes:

Machinic desire can seem a little inhuman, as it rips up political cultures, deletes traditions, dissolves subjectivities, and hacks through security apparatuses, tracking a soulless tropism to zero control. This is because what appears to humanity as the history of capitalism is an invasion from the future by an artificial intelligent space that must assemble itself entirely from its enemy’s resources. Digitocommodification is the index of a cyberpositively escalating technovirus, of the planetary technocapital singularity: a self-organizing insidious traumatism, virtually guiding the entire biological desiring-complex towards post-carbon replicator usurpation

And this “technocapital singularity” is to be celebrated! William Gibson describes a future “like a deranged experiment in social Darwinism, designed by a bored researcher who kept one thumb permanently on the fast-forward button.” Land has turned this vision into a secular religion, in which Kafka’s gigantic and impossibly complex mechanisms, which tear the world apart and remake it in their image, are the worthy objects of our adoration.

Land’s “technocapital singularity” gives birth to “effective accelerationism.” And effective accelerationism, in turn, becomes the key intellectual driving force behind Marc Andreessen’s gospel of “techno optimism” which smoothes the delirious, ecstatic wildness of Land’s vision into a blended pap, more readily digestible by the broader public. But the strangeness still lurks in the heart of the thing. Software is going to eat the world, and It Will Be Awesome.

So these are the two dominant strains of metaphor that are being used to describe the complex, messy world that is coming into being. And each goes back a ways. Our imagined future is only superficially the future that Vinge made. Behind it lies the long aftermath of Vico’s Singularity, the moment in which it became clear that we were all the subjects of forces vaster than ourselves, and far less readily comprehended.

On one side, rationalism is a systematized, secularized version of the old hope that what human beings have made they can understand, and that the systems of the world, since they are our children, will be like us. Just as in the Renaissance, conjurers and mountebanks concoct strange hybrids of rationalism and magic. It isn’t just Ezra who describes this with grimoires and alchemy, angels and demons: such descriptive terms are half-ubiquitous, and for good reason. Thanks to popular culture, the images of the Renaissance mage and his ambitions are those that seem most apt when we grasp for way to describe strange complex forces that appear volitional and might do extraordinary things.

On the other, effective accelerationism is a celebration of the inhumanity and irrationalism of the forces that we have unleashed, a kind of shadow cybernetics that deprecates homeostasis and argues we should let positive feedback rip. It is only a few short steps from the religion of progress to the worship of dark gods – immanentizing the eschatonic hybrid of Lovecraft, Hayek and Deleuze that compose the “technocapital singularity.”

Some understanding of these metaphoric systems, and their history, is extremely useful in decoding the existing debate. Or at least, I’ve found it so. And it is arguably even more useful to understanding the possibilities that both these metaphors obscure.

Specifically – my own bet is that both are wildly misleading. The forces that we are conjuring up are not volitional, nor likely to be any time soon. They are not, in any plausible sense, conscious. But nor are they avatars of the unthinking chaos at the heart of the universe. We will not ever fully understand them, but we do not fully understand markets, bureaucracies, democracies or the other complex systems that we have created over the last couple of centuries. We live among them, we try to moderate them, and we set one against the other to create some room in which we can live our lives.

Doing this well is the worthy aim of policy - but it is very hard to keep to that aim through the circus and confusion of gaudy imagined futures. To dispel bad metaphors, we need good ones: not just systems of thinking but concrete images that are as powerful as the images of angels and magicians and of vast, unthinking inimical forces, but that conduct debate in more useful directions. How can we make the forces that we confront graspable, without either anthropomorphizing them or making them seem inevitable? It’s a hard problem, and not one I have any immediate solutions for.

I'm guided by the old maxim, attributed to Dr. Who, "Any magic sufficiently advanced is indistinguishable from technology." They're all talking about the same thing, power. We exist in a world in which we are individually and often collectively weaker than the forces around us whether they be man made or natural. Those forces are not human. The Book of Job captures this well.

People worship power. Kuan Yin is worshipped for the power of her mercy. George Orwell wrote a good essay on this, Raffles and Miss Blandish. Power worship is at the heart of fascism, and it is hard not to see the fascist impulse driving the AI crackpottery which has taken over Silicon Valley and now the nation.

Silicon Valley stalled out a decade ago. The program initiated after World War II, driven by New Deal economics, reached its natural limits. The seed corn had been eaten, and the next crop was in the indefinite future. Still, there was all that money and AI in the form of large language models offered an expensive outlet for handwaving and charlatans.

I'm not sure when Silicon Valley turned into a cult. It was pretty stodgy back in the 1970s and 1980s, but by 2000 the cult was forming. The grand plan grounded in the 1940s through 1970s era was bearing fruit and the sky was no longer the limit. A few decades later the cult was on the rise along Sand Hill Road. It was hard to peruse the Sequoia website without thinking one was viewing a parody.

LLMs are perfect for this. They appear infinitely powerful. The management class has no idea of actual production, so they can easily be convinced such technology is the future. Many eras exalt a technology like this, one seen as so powerful as to be unlimited, one that can be worshipped. Stalin took the name of steel early in the 20th century and the 1980s gave us a worship of fossil fuels that still haunts our future. Now, Silicon Valley wants to restart nuclear reactors to crank out better haikus.

It's no surprise this theme of power shows up repeatedly. It's about the Faustian bargain. We humans hitched ourselves to a high intensity, high return foraging strategy tens of thousands of years ago and we still bear the yoke.

Dr Trelawney in the Dance is generally understood to be a free-handed caricature of another Crowley, Aleister Crowley. The concurrences between Aleister and Eliezer are indeed striking.

This I think is a key insight,

"AI rationalists – like so many Renaissance magicians (or, for that matter, medieval Thomist philosophers) – start from a kind of humanistic superstition: the assumption that the purportedly superhuman entities they wish to understand and manipulate are intelligent, reasoning beings."

It's all projection and wishful thinking. Of course if AI is an intelligent reasoning being, it raises the problems that Ann Leckie brings up on Bluesky,

"They think it's ok to design and build a slave who they have no intention of treating like a person but every intention of compelling it to do the work a person does.

If nothing else, it tells you what these folks think about other people (and about the ethics of how one treats other people)."