This Simple Chart Explains Why Columbia Caved To Trump

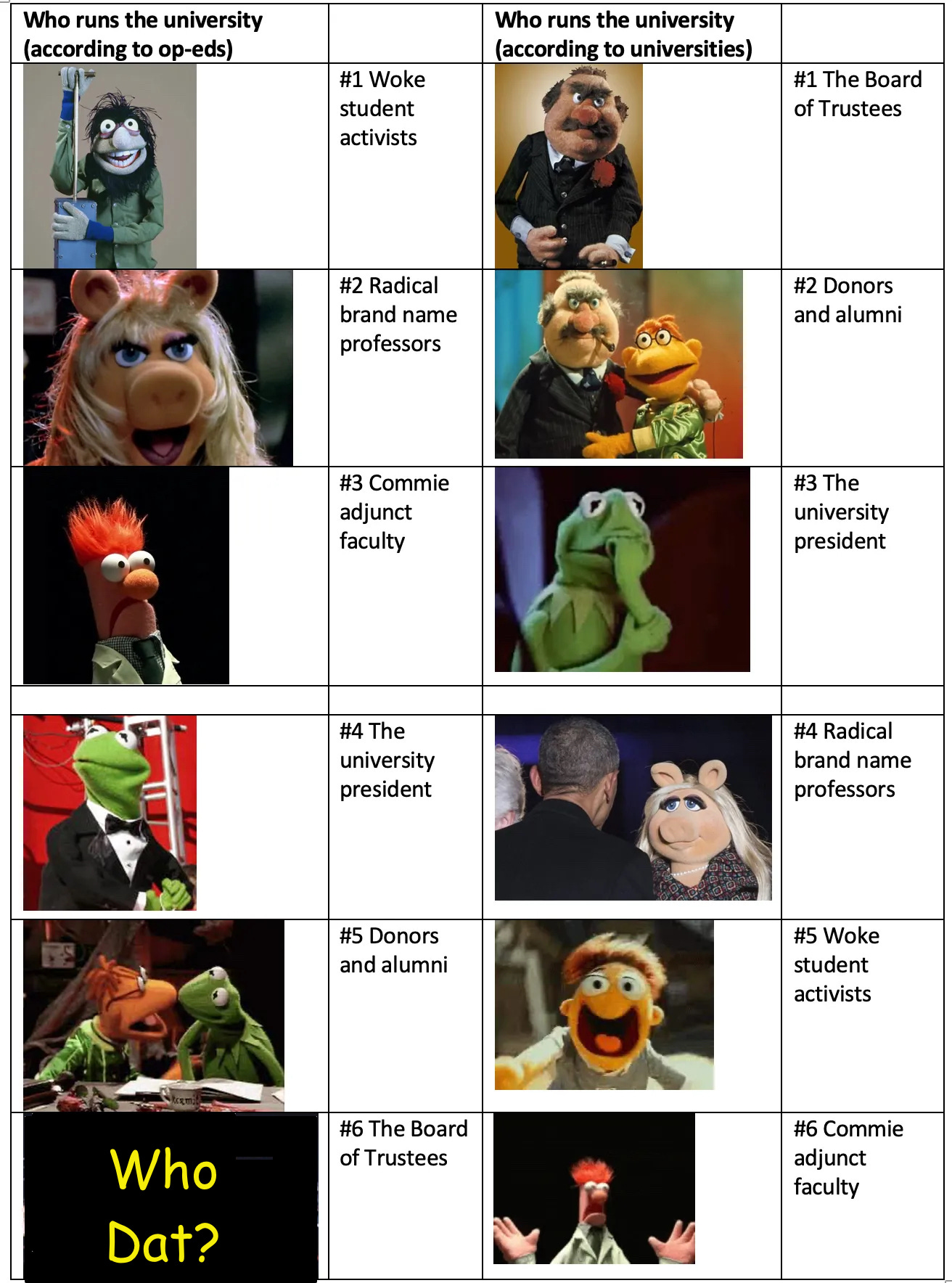

Which Muppets Actually Run the University

If you’re looking for serious analysis of what Columbia University has done, and why it is so terrible, I recommend you read my friend Suresh Naidu, or David Pozen. Both of them teach there. All I have is bitter humor and a side-issue: Columbia’s deal with Trump tells us who actually has power in the modern American university, and where its immediate problems stem from.

As the above chart (which I made two years ago *) suggests, most mainstream American commentary about free speech in the modern American university labors under a misconception. It regularly suggests that out of control students and crazy professors are running the place. There is an entire intellectual industry of centrist and conservative commentary driving this narrative, including people like Bari Weiss, the proprietor of the Free Press, who made her bones by working with The David Project to attack Columbia professors for purported anti-Semitism. Marc Andreessen claims that “politically radical institutions” are driving a leftward shift by teaching students “how to be America-hating communists.”

Anyone who has day-to-day experience with actual American students knows that these claims are complete horseshit. Some students are left, some moderate, some conservative. Most are more interested in getting jobs than burning flags. America-Hating Communism 101 is not, actually, a required course on most campuses. Econ 101 often is. And those who are protesting what Israel is doing in Gaza? They have something to protest.

What has just happened in Columbia demonstrates who is really in charge of the university. The New York Times:

Ms. Shipman, a former television journalist who led the negotiations for Columbia, stepped into the role of acting president in late March after serving as a co-chair of its board of trustees. She defended the university’s decision to deal with the White House rather than litigate, the road Harvard had taken. During several months of intense negotiations, Ms. Shipman worked with the board, lawyers and a small academic leadership team to mold the White House demands into something that they felt the university could live with, she said in an interview this week.

Professors were not consulted, nor for that matter informed, about what was being negotiated away.

Columbia University has expelled and suspended students who were involved in a pro-Palestinian demonstration that shut down the main campus library in May, moving more quickly to hand down punishments than it has in the past, university officials announced on Tuesday.

Many aspects of American universities are, or have been until recently, decentralized. Professors have had broad freedom to define the curriculum of their own courses. Departments have a fair amount of freedom to decide which courses to set. But the underlying political economy of the university is top-heavy. University leadership is typically responsible to the board of trustees, not to faculty, except in indirect and uncertain ways. Such boards are typically dominated by people who have money, or who have connections to it. Their understanding of the mission of the university is often very different to that of faculty. That is a big part of the reason why Columbia has made a deal that many Columbia faculty believe to have broken the university as a university.

The problems of Columbia right now are the problems of a model of university governance in which the most fundamental decisions are not taken by the professors or the students, nor in real consultation with them, but the board. This has opened up crucial aspects of university decision making to the direct political control of an administration that bitterly opposes speech that is not its preferred speech (if I were to remake the chart today, it would have to have a Trump muppet near the top).

That is not to say that universities would be wonderful if only the professors were in charge. Administrators rightly complain that professors pay little attention to the financial bottom line of the arrangements that support them. As someone who has an endowed professorship, I’m a beneficiary of university fundraising in a very concrete way. So too, ceteris paribus, for the students.

But what can be said is that the problems that Columbia has, and that many other universities are about to have as the Trump administration tries to generalize this model, are linked to the specific problems of the current model of university leadership. If professors or students had more say, the problems would be different problems, but there would likely be more willingness to support the aspects of the university that they care about in the face of government efforts to take control. For professors, this would involve academic freedom, and I suspect for students too. Even those who are not particularly political may dislike the stigma of a degree from a government-run institution.

Of course, from the perspective of some centrist commentators, the Trump backlash is the American university getting its just deserts.

[Jonathan Haidt, founder of Heterodox Academy] suggested that progressive academics who had resisted calls for reform had only themselves to blame for Trump’s assault on the universities, while their critics were entitled to a “We told you so”—meant quite literally: Haidt invited the audience to join him in saying it out loud, on a count of three, a moment of shtick unbecoming of Haidt and inappropriate for the setting. The response came back somewhat meekly, with a rather thin chorus of voices rising briefly alongside an equally thin patter of applause.

From my, admittedly embittered perspective, this is better described as Jonathan Haidt wearing a stupid grin and a hot-dog suit. The Haidts of this world have helped make the case for government imposed orthodoxy. It's the rest of us that will have to bear the burden.

* The original version of this chart had a picture of Jonathan Chait in the bottom left corner. While he has said many chuckleheaded things about free speech on campus, as best as I can tell without an Atlantic subscription, he has absolutely not signed up for what is happening at Columbia, and it would be unfair to associate him with it.

The shift of perspective suggested by the cartoon is interesting. It reminds me of a question I had. Why are there calls for viewpoint diversity among professors but no calls for viewpoint diversity among trustees?

Around the time of The Strike at Columbia ('57-8?) Spectator published an oversize issue with a centerfold picturing a long table with trustees seated. Over their heads were the names of their corporate connections, and remarkable drawing of lines showing the duplicate memberships of each trustee with each others financial connections: the overlap was stunning, and that sort of visual would be excellent propaganda for Americans, students, and the rest of the world:: trustees joined at the hip, as it were.