The Village and the Sewer

Behind the "Blueskyism" debate

Back when the kids were small, my family went to a diner that was well known locally for its shtick. As soon as you came in the door, the host/owner would say something rude to you.

When we arrived, it was clear that the host had been at it for decades, and was long past caring. He glanced at us, muttered some predictable and non-specific insult, and we passed in. The whole restaurant had the same vibe. The food wasn’t terrible, but towards the end of the meal, a surprisingly large cockroach squirmed out of a crack near our table, considered its prospects and scuttled back into its darkness. When we told the waitress, she shrugged it off. It wasn’t her problem.

That’s how the “Blueskyism” debate looks to me. Every one to two weeks, some centrist pundit writes a standardized and moderately insulting complaint about the pathologies of Bluesky, Every one to two weeks, the Plain People of Bluesky say rude things back. For both, it’s a highly ritualized performance.

Rather than going through the various examples in detail (they’re repetitive and uninteresting), I want to build on a essay by Ben Recht and Leif Weatherby, reviewing a recent book by Nate Silver (who coined the term “Blueskyism”). Adapting Ben and Leif’s ideas, the fight over Bluesky is a fight between a particular version of the center and a particular version of the liberal left over the nature of intellectual authority right now.

More specifically: much of the variation among centrist and left pundits can be predicted by the answer to a simple question. Does this or that pundit defer more to the intellectual authority of traditional expertise or the intellectual authority of the Silicon Valley model? This disagreement is increasingly being wrapped around a narrower dispute over whether pundits should be punditizing at Bluesky or at X. The political economies of both sites - the differences between the implicit incentives of the two sites’ algorithms - exacerbate this dispute and make it nastier.

The fight between traditional structures of authority and the intellectual model of Silicon Valley is the main theme of Silver’s book, which has just come out in paperback. Silver doesn’t make any secret of which side he is on. He depicts an America that is split between the “Village” - “Harvard and the New York Times; academia, media and government” and his own folks, the “River” of “Silicon Valley, Wall Street, sportsbetting, crypto, even effective altruism” all of which are dominated by “people who are very analytical but also highly competitive.” The River analogy is a reference to the last card in Texas Hold ‘Em poker. Riverians, like professional poker players, understand the odds and play them. Silver is himself a poker player, and suggests you should in general bet on the people who know how to bet.

The problem is that betting on the general usefulness of political and intellectual philosophies (which is what Silver is doing) is compromised by myside bias. Results from cognitive psychology tell us that we are absolutely terrible at seeing the flaws in our own views of the world, but quite good at detecting the flaws in others. Accordingly, while Silver’s book lands some very solid blows against the “Village,” his view of the River is ridiculously self-flattering.

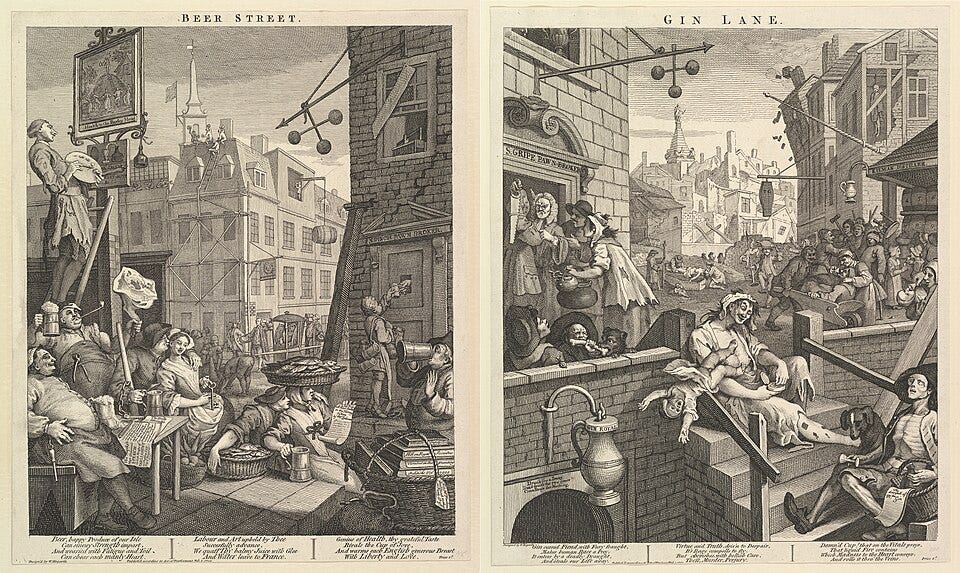

As someone with different priors myself, I would suggest that the more useful and accurate dichotomy is between the Village and the Sewer. That would not differentiate hide-bound traditional elites from calm, calculating ratiocinators, but hide-bound traditional elites from frenzied degenerate gamblers. It would distinguish the censorious curtain-twitchers of Bluesky from the depraved mob-outrage enthusiasts of Twitter/X. On the one side, the blinkered self-satisfaction of the organized professions, as magnified by crowd sourced pressures towards conformism. On the other, the dynamics through which “first principles” and “do your own research” are digested by the intestinal apparatus of algorithms and crowd identification, producing an undifferentiated slurry that is re-devoured in an ecstatic collective communion so that the cycle can begin anew.

These metaphors likely indicate my own particular biases. I’ve thrown my lot in with the blinkered curtain-twitchers. If Blueskyism has problems, and I absolutely believe that it does, the problems of Sewerism seem to me to be much worse. But instead of entering the lists on behalf of one side or other side and being pulled into the shtick, I’d like us to start figuring out how the two work together. Why is it that we (for those of us who live in the US, and some other countries) are trapped in a system where the self-images of both the professions and tech innovation are increasingly organized around their worst rather than their best aspects? It would be nice to know! NB, however, that all the below is at best social science inflected opinion journalism. I’m pulling together a grab bag of personal observations and anecdotes, and trying to weave them together with a few generalizations into a cohesive story. Treat all this as a set of pointers towards a possibly better argument rather than the product of serious investigation,

Blueskyism and Sewerism

As already noted, there’s good evidence that human cognitive psychology is skewed in some quite particular ways. We are extremely bad at detecting the flaws of our own arguments. We are very good, in contrast, at spotting the holes in the arguments of people who we vehemently disagree with. The obvious corollary is that we ought to take criticism extremely seriously. On average, it is much more likely to be right than our own priors.

Hence, I’ll start by acknowledging that there is a lot that is right about the criticisms of Blueskyism! Bluesky indeed often feels like academia and traditional authority on holiday. The platform sometimes has the worst features of a small community in the throes of a Tidy Towns competition gone feral, ensuring that disruptive outsiders don’t get a look in. There is a tangible Village Consensus, which is deeply respectful of traditional expertise and professional knowledge, and acutely sensitive to criticisms thereof. Moral panics are frequent and pervasive, especially around topics (such as AI) that threaten the professional classes. Back in the early days of the platform (I was there from pretty early on), it was silly and giddy and fun. Now it’s End of the World, 24/7.

Equally, prominent critics of Blueskyism, who mostly are primarily attached to Twitter/X, are disinclined to note the problems of the Sewer that they inhabit. If Blueskyism worsens the inherent defects of academia and the professions, Sewerism does the same for the nastiest aspects of Silicon Valley, so that crypto scams, AI boosterism and unembarrassed power worship run together through the gutters of a social media service that does for the town square model of public debate what Nero did for the Olympic Games.

As Recht and Weatherby describe the main current of Silver’s argument:

The ideology is gambling, but the thinking is all reactionary hive mind. The main characters of the later chapters are all from the San Francisco Bay Area, but they spend a disproportionate part of their lives online. These are people like Bankman-Fried and the crypto bros, pseudonymous accounts like roon and Aella, self-made prophets of computational religion like Eliezer Yudkowsky. On the Edge is a celebration of the community that uses their phones to gamble on everything: to place sports bets, to bet on risky stock options, to bet on cryptocurrencies, to bet on elections.

This isn’t an icy-clear River but the Sewer in full spate. Recht and Weatherby compare the logic to a casino, where the house always wins in the end. For my own purposes, I’d compare it instead to meme stocks, an unstable world in which everyone is desperate to be on the winning side of the grift, but regularly half believe the stories that they’re telling themselves and others. Bayes’ Theorem becomes the spawning-point for a myriad of cults. Silicon Valley funders and founders get high on their own supply. And DOGE and other madnesses are released upon the world, and then quickly forgotten, because awkward and embarrassing.

The political economy of bad thinking

Such problems are reinforced by the ways in which the platforms work. And Bluesky and Twitter/X have their own particular tendencies. Critics of social media sometimes lump them together, suggesting that they are slight variants of the same bundle of pathologies. There’s something to this, but there are also very specific pathologies to each. To understand why, you have to have some kind of map of their differing political economies.

It’s easier to start with Twitter/X, where the structural problems are more commonly discussed and better understood. As I see it, the three most important aspects of the system are this. First, and most infamously, the underlying algorithm prioritizes not just posts that are likely to get attention, but posts by Elon Musk and his political allies. Second, it favors posts by people who pay to have their accounts “verified.” Third, it discriminates against posts that link to outside sources.

This has a number of plausible consequences. First, it creates a particular variant of what Paul Krugman calls a Sierra Madre economy, where many, many people try to attract the attention of Elon Musk or one of his close confederates, but very few succeed. The way to strike gold is to say something that appeals to the political priors of these very strange men. This creates a feedback loop where the crazy feeds upon itself and grows ever stronger. Second, the people who want to get verified are very often people who are trying to sell a bill of goods - selling a shitty product, or pumping up some meme coin or meme stock. This means that Twitter/X has a remarkably high ratio of scam to useful content, especially when you account for the pervasive (and often very low-quality), advertising. This combines with the third feature to create an economy of attention that is highly plugged into the fantasy world of crypto and pump-and-dump, and relatively insulated from the more sober world of ordinary reportage. Notably, there is a lot of really wild AI speculation, where ludicrous claims are regularly reinforced rather than corrected. There’s great cultural/economic sociology to be done by someone analyzing the consequences of Twitter/X for the current AI boom and its sustenance.

Bluesky, in contrast, doesn’t rely on a core attention-grabbing algorithm in the same way. You can pick and choose from a multitude of algorithms. While I know of no research on this, my working theory is that most, and likely nearly all, people opt for the default algorithm, which just presents posts from the people you have decided to follow in reverse chronological order. Bluesky doesn’t have any visible means to make money (yet). It does not penalize posts with links to online sources, and some online publications have suggested that it is becoming a valuable source of incoming traffic.

These create an internal political economy of attention that is notably less deranged (again, in my biased opinion) than that of Twitter/X. Still, it most certainly has its demented aspects, which are less a result of arbitrary algorithmic choices than the group dynamics that are transmitted through and underpinned by the algorithm.

Bluesky’s base algorithm means that you are still much more likely to see posts from some people than from others. Those who have lots of followers are obviously more likely to get read. Their posts in turn may get boosted by their readers, so that their readers’ readers are exposed to them, and, if they like them, boost them in turn. This generates preferential attachment dynamics. Even without algorithmic juking, those who are already well known are likely to increase their dominance over time, leading to a highly skewed distribution in which a small number of people get the lion’s share of the attention. In Bluesky’s case, those privileged people and organizations tend overwhelmingly (a) to have external cultural cachet and (b) to have anti-Trump politics. The relative political homogeneity (there are vicious internal arguments of course) is likely a product of Bluesky’s effective origin story as a refuge for those fleeing Twitter after Elon Musk took over. So too, the relatively strong connections to people with academia and expert knowledge (albeit outnumbered by celebrities and politicians in the top reaches).*

All this too has consequences for the internal political economy of attention (as I experience it personally at least: there is surprisingly little real research that I’m aware of). Really awful stuff is rarer than on Twitter/X. Nearly every poster who has lots of followers is not just a denizen of Bluesky. Typically, posters have some significant external reputation that might be dented or badly damaged if they went full catturd2. Equally, unsurprisingly, arguments or statements that align with the site’s politics tend to do well, especially when they are taken up by people with lots of followers. Those that do not so align, do not.

This leads to a close intertwining between Bluesky, mainstream media sources, and the Democratic party, even though Bluesky is significantly more partisan/left than MSM and the Dems and caters to a much more specific demographic. On the one hand, this results in a lot of traffic to places like the New York Times. On the other, there is also regular and bitter contention about how publications, politicians and pundits are too centrist.

There is strong antipathy to Silicon Valley, not just Musk, Andreessen-Horowitz and the rest, but to liberal-tinged and centrist tech types too, and to technologies such as AI that threatens academia, journalism and the established professions. People who use AI generated images get pushback, telling them firmly that this goes against the culture (although this hostility seems to me to be tapering off some). Bluesky’s own people apart, the only tech aligned poaster in the top 100 is Mark Cuban (who is also one of the most frequently blocked people on Bluesky).

The results are high cultural homogeneity, and a strong tendency to criticize and isolate people who don’t share the village’s values. Crusty jugglers watch out! Bluesky is also much more hierarchical than most of its users acknowledge. Bluesky leadership emphasizes the benefits of openness and decentralization, and the extent to which Bluesky provides users with free choices. These are indeed good things on the whole, but they certainly have their own associated pathologies.

The big lesson of preferential attachment is that power disparities can emerge from completely decentralized processes. Those at the top of the distribution of Bluesky play a powerful collective role in shaping what everyone, including they themselves, see, and tend to filter out perspectives that don’t fit their preconceptions. Equally, the structure isn’t centered on one individual, and there isn’t any equivalent of the Twitter/X Hunger Games, where people compete to get Elon Musk’s attention with ludicrous and horrible claims, creating a conveyor belt of crazy from the fringes to the chokepoints of attention.

Sometimes Bluesky hierarchy can have good consequences. After Charlie Kirk’s murder, Bluesky critics like Thomas Chatterton Williams claimed that Bluesky was chock full of people celebrating. Prominent Bluesky users retorted that there was little to no evidence of that in the feed. My anecdotal sense is that there were people celebrating his death on Bluesky, who you could find if you looked for them - but they were not being amplified or shared by the accounts at the center of the social graph. The consensus of the Village, shared by its leaders and enforced by the tacit hierarchies created by skew distribution functions, was that this was not something that Ought Be Celebrated. Those who did celebrate were consigned to the margins.

Mutually reinforcing caricatures

As argued (I), Blueskyism and Sewerism both have their own particular pathologies. As argued (II), these pathologies are reinforced and accentuated by the social media platforms that they are increasingly associated with, at least in the public eye (I have no idea how you would even begin to measure how many of the cultural features of Blueskyism or Sewerism as I have described them are associated with stuff that happens outside their platforms). The most speculative part of my argument is (III). New pathologies are springing up from a self-reinforcing polarization of debate between Bluesky villagers excoriating a tech-intellectual industrial complex that they hate (often with good reason) and Sewer denizens denouncing (often with good reason) a village that seems willfully ignorant of its own parochial interests, blind spots, and genteel corruption.

This third phenomenon is a meta-layer of emergent over-confident generalizations that emerge from the more particular lower-level pathologies of the two forms of expertise and their associated platforms. Again, Nate Silver provides an illustration (in conversation with Tyler Cowen), which touches on things adjacent to what I do meself.

COWEN: What was the last interesting thing you learned from the academic political science literature?

SILVER: Oh boy, this is going to seem like an insult. [laughs]

COWEN: No, no, we’re all for insults here.

SILVER: Look, I read a lot of Substacks and things like that. Oh, my gosh. I don’t know.

COWEN: I think that might be the right answer, to be clear.

[laughter]

SILVER: I think in some ways, what has come out of academic circles has been interesting. I think effective altruism has been interesting, for example. Certainly, critical theory or whatever, the origins of wokeness have had a lot of influence on the discourse more broadly. But I don’t really read a lot of journal articles anymore. Also, a lot of it’s gone on Bluesky, I think, and I can’t tolerate Bluesky, really. It’s too much of a circle jerk.

I think academics have maybe lost influence in that respect. Even though I have great experiences talking to academics, and I’ll do events at universities a couple of times a year.

They also fall into this trap where it’s so reflexively anti-Trump, a lot of it. I’m anti-Trump, in most senses of that term, but something about it has melted the brains a little bit of the nuance and the subtlety. And the slow-cooking method of academia, where you’re supposed to take more time with things, is not always a good match — you being one of the major exceptions — for rapid-fire reaction to the news cycle.

… I think that 90 percent of academic papers would work perfectly fine as blog posts. Including the tone of like, “Okay, I ran some regressions” instead of having Greek symbols and things like that, and the pretense of all of it.

Obviously, I’m not even slightly unbiased. I’m an academic political scientist! Also, maybe it’s worth disclosing here that I had lunch with Silver years ago, back when he was talking more to political scientists, and seemed to think, as did many political scientists, that we were all engaged in a collective endeavor to bring quantitative reasoning to the masses.**

But dismissing academic peer review (which is flawed, and a massive pain in the arse, but which has value) as “the pretense of all of it” is a notably self-flattering choice if you have opted instead for Substack newslettering as your livelihood. It also enables you to dismiss a whole lot of potentially valuable disagreement without ever having to consider it. Conflating academic papers with Bluesky circle-jerks with Greek Symbols and Book-Larning into one indifferent mass of badness allows one to invisibly circumnavigate how “rapid-fire reaction to the news cycle” can melt people’s brains too. As it happens, flash-frying is a whole lot quicker than slow cooking, and without naming names, there are a fair number of Substack quasi-academics, whose brains are sizzling in the heat of a business model that requires them to post confident seeming claims three or four times weekly.

I could find similarly tendentious stuff on Bluesky of course - while I’m biased to be annoyed by the kinds of arguments that reliably annoy me, readers should consider these vexations as a stand-in for a proper “plague on both your houses” argument. The actual point being that if you, as a Blueskyist, want to analyze the defects of Sewerism, go for it, and so too for Sewerists going after Blueskyists. But lack of self-awareness about the defects of your own position, and how the whole insult-swapping model is its own self-perpetuating clusterfuck, is liable to hurt rather than help your case. Making silly and tendentious claims encourages silly and tendentious responses. Ritual insults beget ritual responses as the cockroaches keep on scuttling out.

The current model of debate is an accidental and emergent phenomenon, but one that might as well have been purpose designed to get stupid fights going that distract from the actual problems rather than pointing towards them. There are a lot of problems with the Village model of intellectual authority; so too with the Sewer that threatens to swamp it with fetid semi-solids. But my very strong intuition is that the pathologies of the two are increasingly connected so that they feed off each other. That is not only missed when the one deplores the other without looking to itself or the wider system. It is reinforced.

The self-satisfied ignorance of the Village helps perpetuate the morass of scam and thwarted opportunities that many, perhaps most Americans are trapped in. Ritual denunciations of the Sewer do more to fence all this off from sight than make it better. Many of the Sewer’s most celebrated denizens are more interested (and this is where we get back to Ben and Leif’s casino) in profiting from this misery than addressing it. When crypto interests attack traditional notions of regulation, it’s not from disinterested love of freedom that they’re doing it. The more that the Village gets stuck on denouncing the Sewer (without looking at its own outflows of effluent) and the Sewer gets stuck on denouncing the Village (without recognizing how much it depends on a perpetual supply of suckers), the worse off we all are.

* I note in passing that this has benefited me - while not a big poster, I have more followers on Bluesky than I ever did on Twitter.

** I’m guessing, maybe incorrectly, that some of the specific hostility to political science is connected to an increasingly nasty fight between non-academic pollsters such as David Shor and academic political scientists like Jake Grumbach over the lessons of the last election for future Democratic strategies. But that’s a speculation and a side-note.

I think there are a few distinctions to draw out here. One is that the people who are anti-Bluesky on Twitter (like Silver) are mostly not trying to get the attention of Musk or really enamored of the current state of Twitter (Silver recently posted that Twitter was just good for shitposting now). The other is that Twitter continues to have a lot of stuff that isn't "about" the things at the center of Bluesky/Twitter conflict, ranging from sports to celebrity gossip to AI to porn. Bluesky vs Twitter is mostly about internecine left/liberal conflict, but that's most of Bluesky and not as much of Twitter.

"Bluesky indeed often feels like academia and traditional authority on holiday. [...] There is a tangible Village Consensus, which is deeply respectful of traditional expertise and professional knowledge"

Well that's one way of putting it. It isn't entirely wrong, but it's a bit flattering to the likes of Silver, for a reason pointed out by Dan Davies (I think, "your friend Dan Davies"?):

'It is the same social phenomenon as "people who write for the Express read the Guardian". Everyone wants cachet from the liberal intelligentsia. It's specifically bluesky users they want to be read by. Talking to the audience they get on Twitter is killing them.'

For Silver, it isn't enough to have the privilege of publishing whatever he wants to say with little in the way of sensible editing. He wants the right to be read by everybody. But nobody has that right.