The Sorrowful Tale of the Dread Pirate Roberts

Ross Ulbricht's pardon, and the squalid bargain between Trump and the Silicon Valley right

Last night, Donald Trump pardoned Ross Ulbricht, the founder of the Silk Road online drugs market. This wasn’t a surprise - he’d promised to do it on the campaign trail. Ulbricht has become a kind of secular saint/prisoner-of-conscience for many people in crypto, and some outside it. They view him and the Silk Road as an inspiring tale of how individuals can push back against the government to create a realm of free exchange.

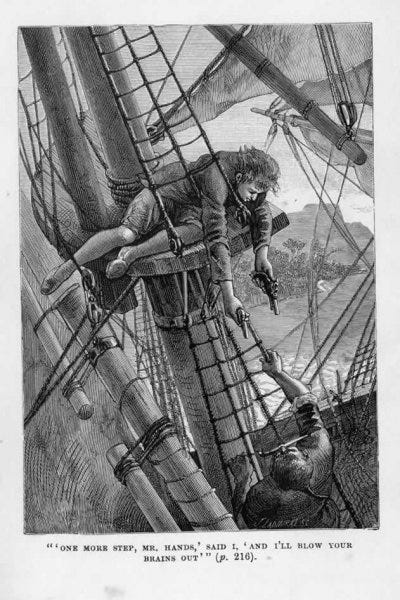

The Silk Road market was only accessible through TOR - an ‘onion routing’ network that provided a high degree of anonymity to those who were willing to install a special browser. They could then buy and sell drugs on Silk Road using Bitcoin, under Ulbricht’s benevolent gaze. The drugs and the profits (Ulbricht made a remarkable amount of money from acting as a middleman) went together with copious quantities of stoner libertarian philosophizing. Ulbricht, who called himself the “Dread Pirate Roberts” even ran a book club in the Silk Road forums, where he eulogized far right libertarians like Ludwig von Mises. You can find lots of the original material here, if you want it, but I’ll warn that much of it is a slog.

I know all of this because a decade or so ago, I spent a lot of time reading through it and doing research. My first book was on the political economy of trust, and how it worked. I still think there are some quite good ideas in it - but the only chapter that is plausibly enjoyable for non-specialists to read, is the chapter on the Sicilian mafia. I had found a qualitative database on cooperation among mafiosi put together by Diego Gambetta, and used it to explore how commercial relations worked among people who had every reason to distrust each other. That required me to pick up bits and pieces of Sicilian dialect, but it was well worth it. As Gambetta put it in his own fantastic book, Codes of the Underworld.

Criminals are constantly afraid of being duped, while at the same time they are busy duping others. They worry not only about the real identity, trustworthiness, or loyalty of their partners but also about whether their partners are truthful when claiming to have interests and constraints aligned with theirs.

Or, in the blunter language of an unhappy commenter on the Hidden Wiki (a kind of guide to where you could find the TOR addresses of specific “Hidden Services” such as Silk Road):

I have been scammed more than twice now by assholes who say they’re legit when I say I want to purchase stolen credit cards. I want to do tons of business but I DO NOT want to be scammed. I wish there were people who were honest crooks. If anyone could help me out that would be awesome! I just want to buy one at first so I know the seller is legit and honest.

Finding “honest crooks” is, for all the obvious reasons, a really difficult problem. It is also a very interesting topic for social scientists who study trust. Can you actually create the necessary trust to underpin transactions - or something that resembles it - under these very difficult conditions? Can you reliably build honor among thieves?

That was why I spent a fair amount of time doing research on what Silk Road users said to each other, and (relying on other people’s research), what they bought and sold. Taken post by post, the material was incredibly dull - there may be more boring reading material somewhere out there than drug buyers and sellers expressing their mutual paranoia about “LEO” (law enforcement officers) who might infiltrate and how they might rip each other off. But as a whole, Silk Road and its successors and rivals added up to a very interesting series of case studies. I wrote a paper on Silk Road, and a couple of popular pieces, but never turned the research into a proper academic article. I couldn’t figure out who might publish it.

All this work gave me some understanding of what Ross Ulbricht had accomplished. He was, by his own admission, not a particularly competent coder. What he was instead was an extremely effective entrepreneur of trust. The reason that Silk Road made money hand over fist was that it provided a place where buyers and sellers could come together to minimize the risk of one ripping the other off. Silk Road worked not only thanks to a number of technologies coming together, but to the efforts of people like Ulbricht to build a social system around them.

As it turned out, the most famous of these technologies - Bitcoin - didn’t work nearly as well as Silk Road users thought that it did. They fancied that Bitcoin provided anonymity: in fact, with patience and ingenuity, it was possible to track transactions (Andy Greenberg’s book, Tracers in the Dark, is the best popular account that I know of, explaining these vulnerabilities and how they were exploited).

A second technology was PGP signatures. PGP, or “Pretty Good Privacy” is a cryptographic system that allows quite secure two way communication, separating the encoding into a “public key” that is used to encrypt messages, and a “private key,” which is used to decrypt them. If you want people to be able to talk to you without others listening in, you make your public key widely available, so that they can encrypt things they say to you, while keeping your private key to yourself.

As a side-effect, this allowed drug sellers on Silk Road and other markets to maintain long term identities without revealing who they were. For example, if a particular PGP public key signature was associated with the identity of the Dread Pirate Roberts, then you could send messages to the Dread Pirate Roberts, secure in the knowledge that only the Dread Pirate Roberts could decrypt them and respond appropriately. This was the serious point behind Ulbricht’s assumption of the soubriquet “Dread Pirate Roberts,” which is a reference to The Princess Bride, where the Dread Pirate Roberts is an identity and a reputation for fearsomeness that passes from pirate to pirate. Similarly, drug dealers could use a PGP key as a long term brand identity, while concealing the actual identity of the individual behind it, combining anonymity with the building up of long term trust along the lines identified by game theorists like David Kreps.

Finally, “escrow systems” like the one created by Silk Road provided a final guarantee. A buyer didn’t necessarily have to trust an individual seller - they could put their Bitcoin payment for a drug shipment in escrow until actual delivery.

All these technologies alleviated the risks of discovery and distrust, and made it easier for wannabe crimers to identify “honest crooks.” But they only worked up to a point. All sorts of scams still happened.

And that was why Ulbricht was unusually successful. He was really good at building up a deeper sense of trust among buyers and sellers on Silk Road. Ulbricht began by selling psychedelic mushrooms himself - but displayed an unusual willingness to figure out compensation when things went wrong. And as he built up Silk Road, he turned this reputation for integrity and fair dealing into a corporate identity (even while claiming falsely that he had inherited the role and identity from someone else). The dorm-room philosophizing was part of the package - a political commitment (plausibly but not certainly sincere) to building up a system in which people could engage freely in buying and selling, far away from the “thieving murderous mits” (sic) of the state.

But it all went wrong. Ulbricht’s fans paint him as a Robin Hood, who didn’t even steal from the rich, but enabled people to engage in private transactions that they ought have been allowed to engage in anyway. They prefer not to talk about how he tried to commission the murder of people (likely imaginary; but Ulbricht didn’t then know that) who he believed were trying to rip him off. As I summarized the sordid details in in one of the previously mentioned popular articles:

Customers had to give mailing addresses to dealers if they wanted their drugs delivered. Under Silk Road’s rules, dealers were supposed to delete this information as soon as the transaction was finished. However, it was impossible for Ulbricht to enforce this rule unless (as happened once) a dealer admitted that he had kept the names and addresses. … If any reasonably successful dealer leaked the contact details for users en masse, customers would flee and the site would collapse. And so, when a Silk Road user with the pseudonym FriendlyChemist threatened to do just that, Ulbricht did not invoke Silk Road’s internal rules or rely on impersonal market forces. Instead, he tried to use the final argument of kings: physical violence. He paid $150,000 to someone whom he believed to be a senior member of the Hells Angels to arrange for the murder of his blackmailer, later paying another $500,000 to have associates of FriendlyChemist murdered too.

For all his protestations, Ross Ulbricht wasn’t no nice guy.

Ulbricht’s enthusiasm to compromise on libertarian principles is a miniature of the broader story of crypto-libertarianism. Silicon Valley pontificators like Balaji Srinivasan enthuse about a world where cryptocurrency undermines the power of the state. But in practice, like Ulbricht, they’re willing to get into bed with the Hells Angels if that allows them to get their way and to make money.

The second popular piece that I got out of my research, which is far more recent, was written for American Affairs, a conservative journal, and published a little before the November election result. It was already clear back then that something very bad was happening, and I drew on the parallels between Ulbricht’s descent and the emerging compromise between the Silicon Valley and Trump. The venue, and my desire to talk to the people who were not fully on board with the program, meant that I took pains to be polite. Still, the underlying criticisms are pretty clear:

It isn’t surprising that entrepreneurs dream of discovering the off-ramp from a world of squalid political bargains to the dizzying freedom of market choice and unlimited technological progress. Perhaps it isn’t even a shock that many are willing to embrace pro-tariff, anti-immigration Donald Trump, who promises to crush their enemies (and commute Ulbricht’s life sentence for drug trafficking while he’s at it). Like Ulbricht, they draw inspiration and justification for their dreams from political philosophy, mixing old thinkers with new machinic visions of technology devouring and transforming humanity.

… Behind all the convoluted future scenarios about the victory of the network state, conquering Bitcoin armies, and the glorious future of techno-optimism lies a business model that mistakenly fancies itself a political philosophy. The notion of moving fast and breaking things apotheosizes into a kind of Hegelian world-spirit, so that the complexities of history boil away, leaving a sludge of repetitive claims about the endless battle between the forces of progress and the armies of darkness, the entrepreneurial disruptors against the defenders of Old Corruption. Profit models blur into grand plans to improve the human condition, and vice versa.

… But the same belief that we are on the verge of a vast transformation—provided only the right forces prevail, and the wrong ones are defeated—is leading in some unhealthy directions. A technological faction … has become increasingly hostile to open debate with those who disagree with them, and to understandings of progress that are not fully consonant with their own.

Again, this is not hypocrisy, but the ordinary workings of human minds. Inside the bubble, the contradictions are invisible. From outside, they are glaringly obvious. To promote open inquiry and free, market-based technological progress, you need an open society, not one founded on the enemy principle. The understandable desire to escape criticism, misunderstanding, and the frustrations of ordinary politics does not entail the radical remaking of the global geoeconomic order to confound the New York Times and its allies. … Over the last few years, Silicon Valley thinking has gotten drunk on its own business model, in a feedback loop in which wild premises feed into wilder assertions and then back. It’s time to sober up.

It has gotten visibly worse since then (or perhaps it is just that the worse parts are more visible). Some of the conciliatory things I say in the article are not things I would say today. Parts of Ross Douthat’s interview with Marc Andreessen are genuinely chilling. Many prominent people on the Silicon Valley right ain’t no nice guys either. They want to go after their perceived enemies, and destroy them.

The reason why Ulbricht seems attractive - why his cause has gotten support from some surprising people - is that he seems superficially to exemplify a kind of libertarian ideal of a world where the violence of the state would give way to free and voluntary transactions between consenting individuals. But the truth is that Ulbricht was quite as willing to employ violence to go after his enemies as the state that he condemned. Now, a substantial chunk of Silicon Valley soi-disant liberaltarianism is eagerly making the same kind of deal with Donald Trump.

Not everyone. Vitalik Buterin, the primary founder of Ethereum, is explicitly distancing himself and the foundation he helps run from this bargain. Tyler Cowen, who I was personally unhappy with before the election, is now spending some intellectual capital warning about how it may all go wrong. Still, the Ulbricht pardon - and the political bargain that it represents - tells us a lot about the tendency of purported pirate utopias to degenerate into squalid quasi-tyranny. Projects to build Galt’s Gulch tend again and again to turn into deals with the worst elements of government, when they weren’t actually such deals right from the beginning.

"Silicon Valley pontificators like Balaji Srinivasan, Marc Andreessen and David Sacks enthuse about a world where cryptocurrency undermines the power of the state. But in practice, like Ulbricht, they’re willing to get into bed with the Hells Angels if that allows them to get their way and to make money."

I am wondering: Is mafia where libertarianism ends when taken to its logical conclusion?

Great description of it all from crypto to the sleazy ethics of libertarianism. People forget, or try to obsfucate, that the democratic state exists to facilitate safe commerce, and Silk Road shows the contrary.