The cult of the founders

Elon Musk is a prophet trying to do a priest's job

Noah Smith wrote a “Elon Musk as superhero/supervillain” post over the weekend, which clearly reflected, as he indeed suggests, some of the general perceptions of Elon Musk still-gets-shit-done in Silicon Valley, even among people who deplore much of what he has become. It reminded me of a somewhat less flattering piece that I wrote in May of last year, back before I had a newsletter.

I think that the piece still holds up extremely well, but I would think that, and as I have a busy week, and election stresses that make it hard for me to write and think coherently, here it is, in very lightly edited form. The one thing I would add to the below is that if the proposed theory is right, then Elon Musk - even if you grant Noah’s Space-X point - is not going to be good for the U.S. government if the worst comes to the worst. Prophets who are good at inspiring elite cadres into frenzies of productivity are likely to be terrible at managing complex systems of rules with associated political economies. The US government post-Elon will bear a strong resemblance to Twitter - efforts to blow the system up in the belief that it is full of inefficiencies and that something better will surely emerge, and ‘ah well nevertheless’ shrug emoji responses when it doesn’t.

_____

Here’s a half-developed theory of Elon Musk that I’ve been nurturing for a while. I’ve trotted it out informally at a couple of meetings, and I’m not completely convinced it is right, but it’s prima facie plausible, and I’ve gotten some entertainment from it. My argument is that Musk is doing such a terrible job as Twitter CEO because he is a cult leader trying to manage a church hierarchy. Relatedly – one of SV’s culture problems right now is that it has a lot of cult leaders who hate the dull routinization of everyday life, and desperately want to return to the age of charisma.

The underlying idea is straightforward, and is stolen directly from Max Weber – see this handy Weber on religion listicle for the background. Weber thinks that many of the stresses and strains of religion come from the vexed relationship between the prophet and the priest.

Prophets look to found religions, or radically reform them, root and branch. They rely on charismatic authority. They inspire the belief that they have a divine mandate. Prophets are something more than human, so that some spiritual quality infuses every word and every action. To judge them as you judge ordinary human beings is to commit a category error. Prophets inspire cults – groups of zealous followers who commit themselves, body and soul to the cause. Prophets who are good, lucky, or both can reshape the world.

The problem with prophecy is that ecstatic cults don’t scale. If you want your divine revelation to do more than rage through the population like a rapid viral contagion and die out just as quickly, you need all the dull stuff. Organization. Rules. All the excitement – the arbitrariness; the sense that reality itself is yielding to your will – drains into abstruse theological debates, fights over who gets the bishopric, and endless, arid arguments over how best to raise the tithes that the organization needs to survive.

Weber calls this the “routinization of charisma.” Religion becomes a matter not for prophets, but priests – specialized administrators of the divine, who are less about ripping up rule books than writing and enforcing them. Prophets unsurprisingly, hate this transformation into mundanity.

If you’ve followed Silicon Valley at all over the last two decades, you barely need to read the rest of this article. The parallels between founders and prophets are very obvious, as are the cultish aspects of Silicon Valley itself. It really does have the flavor of a millenarian religion, with all the fervor, reforming zeal and hagiomachy you could ask for. Not just snake-oil, but quarrelsome snake handlers.

This in turn helps explain (a) why Musk is doing such a terrible job, and (b) why he appeared to have so much initial support from other Silicon Valley founders, as well as venture capital evangelists.

Looked at objectively, Musk was very good at the prophet stuff for a long time. Inspiring belief in his unique, quasi-divine genius? Check. Getting Stakhanovite levels of effort from his devoted cadre of higher servants? Check. Inducing others to believe that his arbitrary shifts in policy were the product of inspiration rather than peevish frenzy? Check. Inspiring adulation from millions of adoring followers? Check. In fairness, this may not have been all. There are a lot of would-be prophets and few succeed. I have heard from SV funders that he was far better than most of his peers at thinking through the necessary steps to achieve his goals.

But prophecy only goes so far, even when it is well executed. Good prophets know how to inspire the zeal of the faithful. They don’t necessarily have the social and political nous to deal with unbelievers, or to reach grudging but necessary accommodations with them. Often, indeed, disagreement is treated as being tantamount to heresy. Nor are prophets good at working with routines, which are antithetical both to their self image and their style of operation.

And that helps us understand why Musk has been such a disaster for Twitter. He does not deal well with people who don’t worship him. As prophets do, he takes everything personally, and has no particular understanding, nor inclination to understand, the institutionalized forms through which big industrial societies sublimate disagreement and conflict. When government agencies tell him he can’t say random shit as CEO that affects the trade price, he doesn’t want to hear it. When a government lawyer rejects his divine authority by deposing him as though he were a normal CEO, he later tries to get the lawyer fired, threatening to stop working with the law firm that employs him, and delivers on his threat. When Twitter’s rules prevent Musk retaliating against this or that enemy of the moment, the rules are changed by fiat.

The creation of routine; the maintenance of expectations; the building of steady and predictable relationships. All these things are antithetical to his operating style. But they are part of the ordinary process of doing business, and of managing a vast operation that has vast numbers of users, most of whom don’t belong to his cult (characteristically, he gets the algorithms rejiggered so that they are repeatedly exposed to his divine effulgence, whether they want it or not). Most of the advertisers that Twitter has relied on are businesses run by priests. They want orderliness. But Musk keeps on doubling down on his divine authority to do what seems good to him right now. He is a prophet, and that is what prophets do.

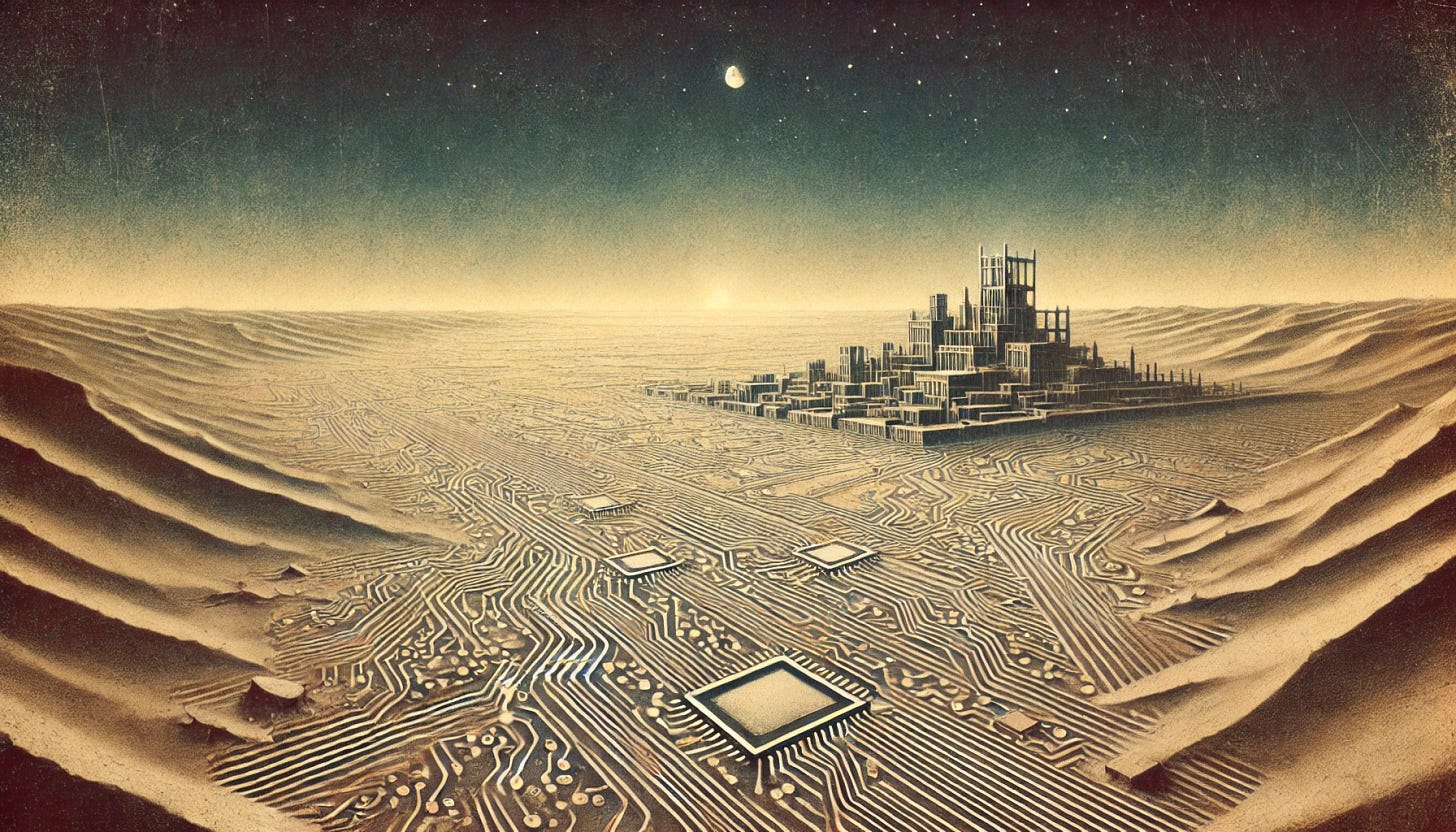

Furthermore – my theory goes – this is one part of the explanation for why so many of his fellow founders cheered Musk on. They too are disillusioned prophets. Once, they believed that software would eat the world. They’d ride their sandworms from the desert through the shield to their own glory and the despair of their enemies, smash everything up, and create a galactic empire of inspiration and awesomeness. Instead, they found themselves managing self-ramifying and self-perpetuating empires of bureaucracy, submerged beneath memos and trivial decisions, and worst of all, dealing with fucking HR and surly and subordinate employees who didn’t share their values, nor behave as worshipfully as they ought have done.

There is a lot more to Silicon Valley workplace politics than this, but I would guess that these kinds of resentments among leaders play a fairly significant role. What they are now doing isn’t what they thought they were signing up for.

So when Musk swoops in, buys a big company that is notoriously badly managed, and promises to cut away the bureaucracy, make the big necessary decisions, and show the world what a real Silicon Valley CEO looks like, is it any wonder that his fellow founders, and their hangers-on and financiers were cheering? Rip out the routinization, and let all that raw charismatic magnificence do its thing, just like they thought it would when they were in their twenties.

Of course, it turns out that propheting is a terrible business model at scale. Weber indeed suggests that there is something fundamentally immature about those can’t accept the complexities of a routinized world and deal with them. The story of Twitter’s aging boy-king (and he does, somehow, seem creepily boyish beneath the wrinkles), is in part one of the inadequacies of the cult-leadership style when you are trying to run a big complex public facing company. You can’t just ignore routine, and minister to the cult. You need to keep a lot of non-worshippers happy too.

Great analysis, and really explains Musk's weird behavior at Trump's rallies: he's chasing that prophetic high again, and it makes him feel Young! (jump!)

By same count, nothing is more terrifying than the idea of Musk in charge of any government office.

A lovely and illuminating analogy. As a vet of 30 years in the SV trenches, I agree with everything you've said here. Its hard for people who didn't live through it to grasp, but in early days what SV produced looked a lot like magic. A personal computer, lookzury! The Internet, a dream made real. A stick of gum that holds 1000 songs, a computer in your pocket. But all that low-hanging hardware fruit (made possible mostly by government funding of R&D in the 50s and 60s) has been long plucked. A lot of hardware pioneers fell by the wayside as hardware became a commodity (mostly thanks to IBM and Microsoft, Intel may be the exception to prove the rule. Most of our tech overlords are software guys who proved more adept at throat-cutting competition (Gates) or investment politics (Andreesen, Theil), where the real money is. I just realized Musk tries to straddle both hardware and software. He's had the classic combo of an eye for opportunity, ruthless determination, a quick but not too deep mind, and a world-spanning ego, but its his incredible insecurity that keeps him from being Steve Jobs, the archtype of SV techlords. He's accidentally accumulated enough capital that he can coast on the fumes for the rest of his life cosplaying a 50's sci-fi engjneer saving the world, but he'll never let go enough to let the grownups build something that lasts.