The AI democracy debate is weirdly narrow

There are plausible reasons for how it ended up that way

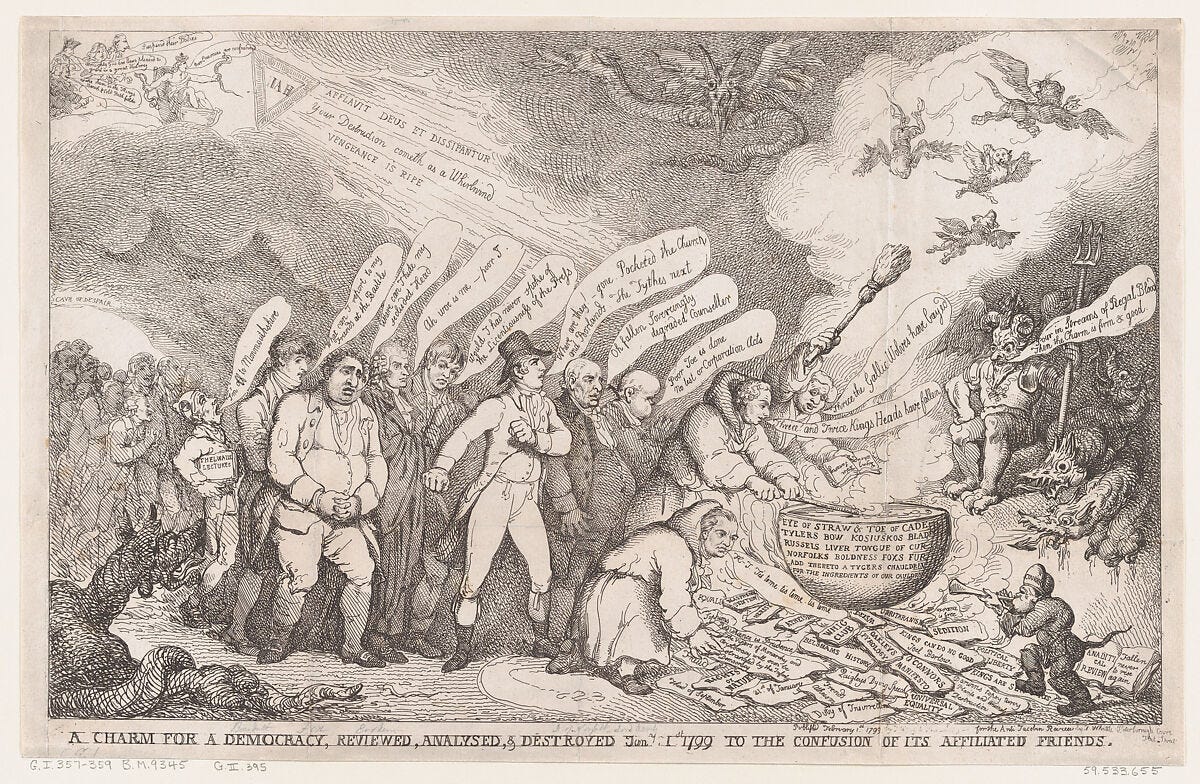

[Cartoon of bewildering 18th century democratic controversies, courtesy of the Met]

Hahrie Han and I have a new paper, which has just been published by the Knight First Amendment Institute. We contend that when people in the AI debate talk about democracy, they usually do so in strangely limited ways. This obscures how AI might affect actually existing democracies.

Crudely put, we suggest that many AI people would prefer a version of democracy that gets rid of the politics. That not only misses the point of what democracy is, but risks ignoring a multitude of urgently important problems and questions. How does actually existing AI affect people’s understanding of politics? How might it reshape the ways in which groups and parties operate? What are the likely consequences of the efforts to turn LLMs into political-cultural chokepoints (see e.g. the Trump administration’s “anti woke AI” executive order)?

So what, exactly, are we disagreeing with? Existing debates about AI and democracy regularly suggest using AI to make democracy more deliberative and representative, if not necessarily more powerful, or alternatively want democratic tools to provide legitimacy to AI without any real accountability. Take, for example, this OpenAI solicitation from two years ago for applying democracy to AI and vice versa:

We believe that decisions about how AI behaves should be shaped by diverse perspectives reflecting the public interest … We are seeking teams from across the world to develop proof-of-concepts for a democratic process that could answer questions about what rules AI systems should follow. … Beyond a legal framework, AI, much like society, needs more intricate and adaptive guidelines for its conduct. For example: under what conditions should AI systems condemn or criticize public figures, given different opinions across groups regarding those figures? How should disputed views be represented in AI outputs? Should AI by default reflect the persona of a median individual in the world, the user’s country, the user’s demographic, or something entirely different? … While these initial experiments are not (at least for now) intended to be binding for decisions, we hope that they explore decision relevant questions and build novel democratic tools that can more directly inform decisions in the future. … By “democratic process,” we mean a process in which a broadly representative group of people exchange opinions, engage in deliberative discussions, and ultimately decide on an outcome via a transparent decision making process.

That all sounds anodyne enough, and indeed, that is exactly the problem. It is too anodyne.

The OpenAI solicitation wants representativeness. The most popular approach to ensuring this in debates these days is ‘sortition’ - picking a representative sample of the population so as to create a ‘minipublic’ that notionally resembles the public as a whole (the same rough percentages of liberals and conservatives etc). The solicitation wants these representative people to engage in “deliberative discussions,” where they politely exchange views with each other, and update their own perspectives when they hear good counter-arguments. These discussions would center on questions that AI labs have tended to see as a massive pain in the arse, while avoiding topics that are central to their profit models (who decides on the release of new versions? who gets the money?) And all this is to be non-binding, unless OpenAI decides to the contrary at its own discretion, at some indefinite point in the future.

Such proposals don’t have much to do with real life democracy. Actually existing democracy, bluntly put, involves actors struggling over power and resources. That isn’t enormously attractive much of the time, but such is politics. Given how human beings are, the great hope for democracy is not that it will replace power struggles with disinterested political debate. It is that it can, under the right circumstances, moderate that struggle so that it does not collapse into chaos, but instead produces civil peace, greater fairness and some good policies and other benefits, albeit with great pain and a lot of mess.

In the essay, Hahrie and I explain why the existing AI democracy debate misses all this, and put forward an alternative perspective on politics, based on contentious publics. Again, if you are interested, go and read it.

But there is an underlying question we don’t really talk about much. Why has the AI-democracy debate ended up centered on this particular understanding of democracy? Cynics might retort that this is all hypocritical window-dressing, but I think they would be wrong. Go to a workshop or conference: there are many people who deeply, sincerely, believe in this vision. While the profit model is enormously important and helps explain the sharp limits in implementation (as well as, perhaps, why there is less talk of democracy at all now that it is out of fashion in America), it doesn’t tell us why the debate ended up focusing on deliberation and sortition, rather than some other set of proposals.

My theories about this are highly speculative, which is why they didn’t make it into the paper. But they are in part supported by one of the great books of modern political theory, Hanna Pitkin’s The Concept of Representation. This book is several decades old, but remarkably applicable to current debates.* It suggests that the kind of democracy that deliberation-sortition points toward is one that is likely to be particularly congenial both to sincerely motivated engineers and to those who are more directly self-interested.

Pitkin wrote her book long before the resurgence of interest in sortition and mini-publics, and focused on arguments for “proportional representation” instead. But she captures the logic of more recent arguments extremely well. These, too are examples of what Pitkin calls “descriptive representation.” Here, the notion is that we ought be represented in politics by people who resemble us in some important way. The best way to represent the general public is through a smaller body that resembles it across the most important dimensions.

Such an assembly, proportionalists maintain, must be “the most exact possible image of the country.” It must “correspond in composition with the community,” be a “condensation” of the whole, because “what you want is to get a reflection of the general opinion of the nation.” Other proportionalists invoke the metaphor of a map, apparently first articulated in a speech before the Estates of Provence in 1789 by Mirabeau (himself no advocate of proportional representation). “A representative body,” he said, “is for the nation what a map drawn to scale is for the physical configuration of its land; in part or in whole the copy must always have the same proportions as the original.”

More specifically:

Truly, as the map represents mountains and valleys, lakes and rivers, forests and meadows, cities and villages, the legislative body, too, is to form again a condensation of the component parts of the People, as well as of the People as a whole, according to their actual relationships.

Of course, just as with maps, those who assemble a minipublic have to decide which features the map ought focus on, and which it ought leave out. The map cannot include all the details of the original, for fear it becomes a Borgesian monstrosity. As Pitkin puts it:

Perfect accuracy of correspondence is impossible. This is true not only of political representation but also of representational art, maps, mirror images, samples, and miniatures.

Such problems are highly familiar to software engineers, much of whose stock-in-trade consists of neat mathematical techniques for generating imperfect but usable mathematical and statistical representations of more detailed and complex wholes.

From this perspective, the political theorist’s notions of descriptive representation and the computer scientist’s notion of a lossy representation merge into each other very nicely. It isn’t surprising that engineers like the notion of minipublics, which seem like a implementation of the kinds of abstractions that they deal with every day, albeit running on human political interactions rather than software code.

The more subtle problem, however, is that this is a theory of democracy as the provision of information about what the public thinks, more than it is a theory of democracy as decision making. Pitkin again:

Representing [under this theory] means giving information about the represented; being a good representative means giving accurate information; where there is no information to give, no representation can take place.

The legitimating notion of descriptive representation is that the map is a good working description of the whole - it may not perfectly represent that whole, but it is as good as we are going to be able to do in the real world. The smaller assembly is legitimate, then, because it tells us, more or less, what the larger public might have said if we magically had the technology to consult it en masse. Moreover, if you are a techie, you can immediately start thinking about neat tricks you might employ to make the assembly better representative of the public, better able to function and so on. Improving democracy begins to resemble the kind of technical problem you have been trained to work on, and you want to get to work on it.

The problem, however is that this mode of representation is highly limited. The logic of a representative assembly is

not a matter of agency, of being authorized to commit others, of acting with a later accounting to others. It is not an “acting for” but a giving of information about, a making of representations about; hence it entails neither authorization nor accountability. That is why theorists of descriptive representation so often argue that the function of a representative assembly is talking rather than acting, deliberating rather than governing.

Or, as Hahrie and I suggest, it is democracy without the politics. If, for example, OpenAI convenes a “broadly representative group” of members of the public to deliberate about how to represent disputed views in AI, that group has not, actually, been delegated by the public to represent its views. It doesn’t report back to the public. It does not have power to make binding decisions on behalf of the public. If members of the general public want to yell at the broadly representative group because it has come to conclusions that they think are weird or wrong, good luck to them! The group has probably dissolved back into its component anonymous members before the general public has a chance even to find out what it has decided ought be done.

All of that, then, provides a plausible explanation for why the democratic AI debate is so weirdly narrow, both in the solutions it proposes for democratic oversight of AI, and in the possible implementations of AI to improve democracy. One, fashionable theoretical approach to democracy - combining sortition with deliberation to produce ‘mini-publics’ - has the enormous advantage of scratching two itches simultaneously. On the one hand, it looks really attractive to sincere techies who want to make democracy better. On the other, it promises the more cynical that they can get some democratic legitimation for farming out decisions on vexing and unprofitable problems that they would prefer not to have to decide on themselves, without any troubling expansion of political accountability.

Pitkin points out the limitations of this understanding of politics:

there is no room within such a concept of political representation for leadership, initiative, or creative action. The representative is not to give new opinions to his constituents, but to reflect those they already have; and whatever the legislature does with the nation’s opinions once expressed is irrelevant to representation.

But if you replace “the legislature” in that sentence with “President Macron” or, for that matter, “the AI labs,” you can see why this limitation might look to some like an advantage. When minipublics come to politically inconvenient conclusions, those conclusions can be ignored.

Again, this should not be taken as license for general cynicism. I can testify that there are many genuinely idealistic people working on AI and democracy. They often have great and intelligent things to say, and have to fight difficult internal battles to get the resources to do what they are doing, since it does not visibly contribute to the bottom line. Still, the more that democratic politics moves away from the mere provision of information about what a public purportedly thinks, and towards actual democratic decision making and control, the more difficult those battles are likely to become.

* I’m enormously grateful to my friend, the information scholar, Nate Matias, for identifying its contemporary relevance and urging me to read it (I’d known about it, but only in the vague way that you know about books that you feel you really ought to peruse sometime but suspect you never will).

AI has reproduced, yet again, the idea that the median view of the US political class has some normative claim to centrality. Both Grok (far-right) and DeepSeek (CCP) have shown that it is perfectly possible to give answers reflecting different background assumptions. But people still "Ask ChatGPT" and expect to receive objective truth.

A central question here is: which country is being represented? On the assumption that the US is already a write-off, it's important to develop digital representations of the democratic world which don't depend on the whims of fascist billionaires.

Well, thanks; this was eye-opening for me in this way: that there are idealists endeavoring to have this powerful thig do good.

My impression from reading the statements of the 'big important men' in ai is that there's a thinking that they are creating, even incarnating, a powerful thing that's under their control. It will consume terabytes of electric energy to do so, with consequences for most of our fellow rate-base members. As in higher costs or routine disconnects from the grid for those who've found some cost relief by signing up for the peak- load- period disconnect rate. There's not enough capacity to keep grandma warmed or cooled to feed Andreesen's new theology.

To civic representation: I've known for twenty+ years that there was sufficient computing power in ESRI's ArcView GIS software that any reasonably- sized civil engineering firm or local or state government agency could take Census survey data and crank out rightly apportioned, logical, easily understood voter districts to more equitably insure a representative distribution by area and population. A map, if you will. And it could be done by a small team or teams within a year, and updated every ten years in a matter of days.

But that doesn't allow for the jiggery-pokery of people who wish to concentrate power for their particular purposes- which more and more appear to be about the accumulation of unholy concentrations of money. Which is what it appears that the owners of this new cool thing want now for themselves.

Sincerely, thanks for this discussion. Think I'm going to pick up another good Aladdin kero lamp from the Amish hardware store, and another five gallons of K-1 in addition to finishing up my woodshed project and split and stack the two cords of free -fall oak and ash. Winter's coming.

Tim Long, just up the hill from Lock 15.