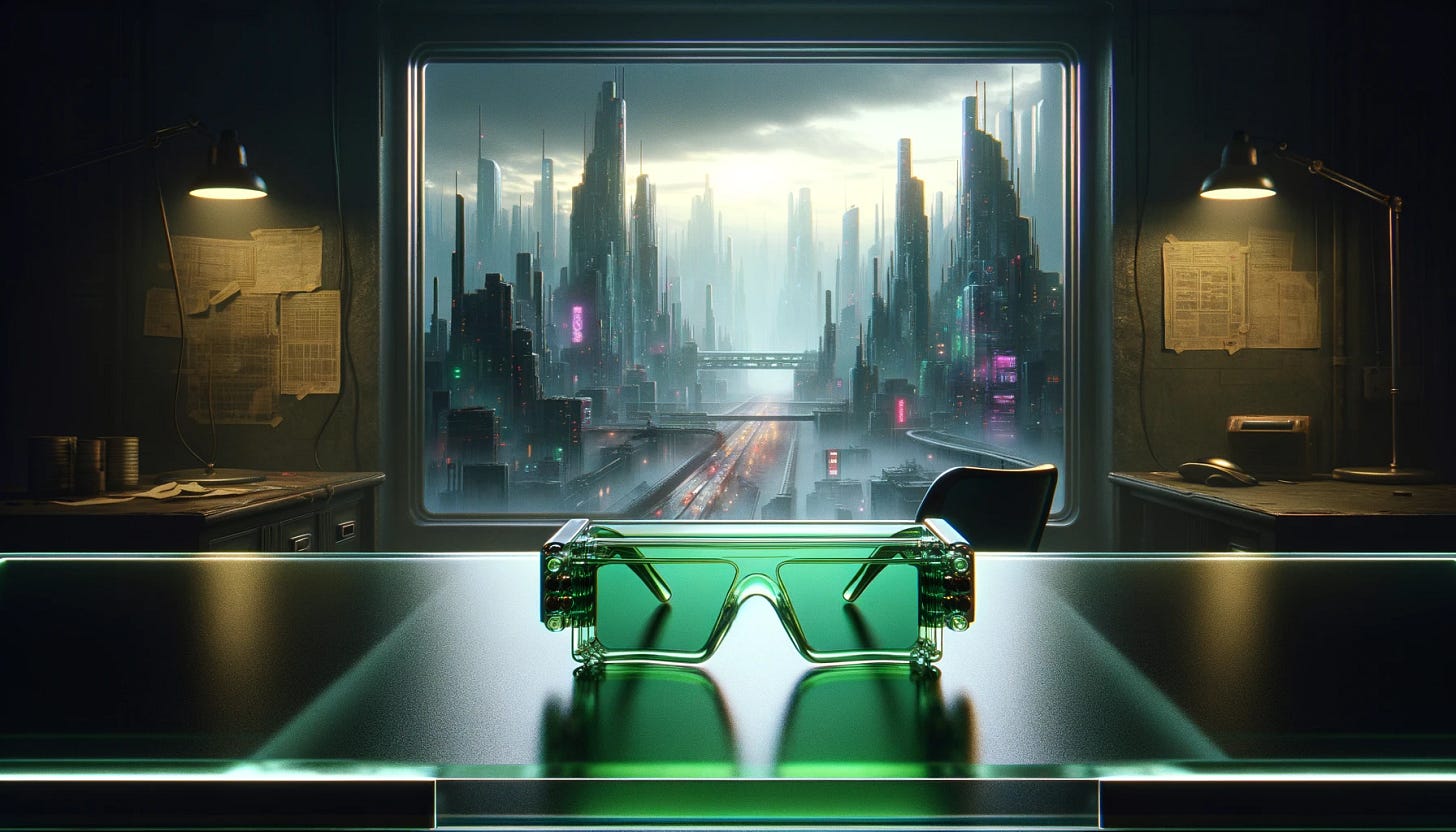

Today's hackers wear green eyeshades, not mirrorshades

Accountancy as a lens on the hidden systems of the world

When reading Cory Doctorow’s latest novel, The Bezzle, I kept on thinking about another recent book, Bruce Schneier’s A Hacker’s Mind: How the Powerful Bend Society’s Rules and How to Bend Them Back. Cory’s book is fiction, and Bruce’s non-fiction, but they are clearly examples of the same broad genre (the ‘pre-apocalyptic systems thriller’?). Both are about hackers, but tell us to pay attention to other things than computers and traditional information systems. We need to go beneath the glossy surfaces of cyberpunk and look closely at the messy, complex systems of power beneath them. And these systems - like those described in the very early cyberpunk of William Gibson and others - are all about money and power.

What Bruce says:

In my story, hacking isn’t just something bored teenagers or rival governments do to computer systems … It isn’t countercultural misbehavior by the less powerful. A hacker is more likely to be working for a hedge fund, finding a loophole in financial regulations that lets her siphon extra profits out of the system. He’s more likely in a corporate office. Or an elected official. Hacking is integral to the job of every government lobbyist. It’s how social media systems keep us on our platform.

Bruce’s prime example of hacking is Peter Thiel using a Roth IRA to stash his Paypal shares and turn them into $5 billion, tax free.

This underscores his four key points. First, hacking isn’t just about computers. It’s about finding the loopholes; figuring out how to make complex system of rules do things that they aren’t supposed to. Second, it isn’t countercultural. Most of the hacking you might care about is done by boring seeming people in boring seeming clothes (I’m reminded of Sam Anthony’s anecdote about how the costume designer of the film Hackers visited with people at a 2600 conference for background research, but decided that they “were a bunch of boring nerds and went and took pictures of club kids on St. Marks instead”). Third, hacking tends to reinforce power symmetries rather than undermine them. The rich have far more resources to figure out how to gimmick the rules. Fourth, we should mostly identify ourselves not with the hackers but the hacked. Because that is who, in fact, we mostly are.

These four precepts are the adenine, cytosine, guanine and thymine of Cory’s two Martin Hench novels to date. Hench, the protagonist, is very clearly a hacker. But he doesn’t wear mirrorshades or get wasted chatting to bartenders with Soviet military-surplus mechanical arms. He’s not even unusually adept with computers. Hench’s tastes and habits are mostly California-prosperous with a moderate bohemian edge. They’re no more avant-garde than those of hundreds of thousands of other Americans with boring seeming jobs. What Hench is, is a forensic accountant. He’s unusual because of his skill and passion for understanding money flows, and the traces that they leave behind. Like traditional cyberpunk hackers, he’s a gun for hire, whose attitude to the law is pragmatic rather than reverential. And in the The Bezzle, he’s neither a black hat nor a white hat, but a whitish shade of grey; compassionate and ethical according to his private principles, but not yet fully enlisted in the War against the System.

I want to avoid giving direct spoilers - The Bezzle is a fun read, and more fun if you don’t know exactly what is coming. But the fun has a sharp political edge. It’s a little like Cory’s earlier novels explaining hacking to teenagers, but it’s not written for teenagers. It’s an all-ages show, for people who want to understand the complex financial and political systems of the world, and how they’re being hacked.

The book’s plot is constructed to smoothly incorporate explanations of how applied tax and finance has become a writhing morass of intersecting hacks and kludges. It tells the reader how so-called “real estate investment trusts” enable tax-scams. What SPACs - “Special Purpose Acquisition Companies” - are, and what they allow you to get away with. How PACER turned nominally accessible court records into a system for making lots of money, and how the late Aaron Swartz (who was a friend of mine and Cory’s) tried to push back. Equally, Cory makes it perfectly clear that none of this is a fair fight. The bad guys have far more resources than the good guys. They can hack the rules and the systems of money and law enforcement far more easily and far more effectively.

Still, there are things you can do to fight back. One of the major themes of The Bezzle is that prison is now a profit model. Tyler Cowen, the economist, used to talk a lot about “markets in everything.” I occasionally responded by pointing to “captive markets in everything.” And there isn’t any market that is more literally captive than prisoners. As for-profit corporations (and venal authorities) came to realize this, they started to systematically remake the rules and hack the gaps in the regulatory system to squeeze prisoners and their relatives for as much money as possible, charging extortionate amounts for mail, for phone calls, for books that could only be accessed through proprietary electronic tablets.

That’s changing, in part thanks to ingenious counter hacking. The Appeal published a piece last week on how Securus, “the nation’s largest prison and jail telecom corporation,” had to effectively default on nearly a billion dollars of debt. Part of the reason for the company’s travails is that activists have figured out how to use the system against it:

a coalition led by the New York-based advocacy organization Worth Rises passed first-of-its-kind legislation in New York City to make jail calls free … Worth Rises and national partners contested the deal, arguing to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) that the merger would harm incarcerated people by reducing competition. … explained that Platinum’s investment in the prison telecom giant presented substantial reputational and financial risks … In September, the Pennsylvania State Employees’ Retirement System denied Platinum Equity a $150 million investment, citing the extensive negative press surrounding Securus.

In other sectors, where companies doing sketchy things have publicly traded shares, activists have started getting motions passed at shareholder meetings, to challenge their policies. However, the companies have begun in turn to sue, using the legal system in unconventional ways to try to prevent these unconventional tactics. Again, as both Bruce and Cory suggest, the preponderance of hacking muscle is owned by the powerful, not those challenging them.

Even so, the more that ordinary people understand the complexities of the system, the more that they will be able to push back. Perhaps the most magnificent example of this is Max Schrems, an Austrian law student who successfully bollocksed-up the entire system of EU-US data transfers by spotting loopholes and incoherencies and weaponizing them in EU courts. Cory’s Martin Hench books seem to me to purpose-designed to inspire a thousand Max Schrems - people who are probably past their teenage years, have some grounding in the relevant professions, and really want to see things change.

And in this, the books return to some of the original ambitions of ‘cyberpunk,’ a somewhat ungainly and contested term that has come to emphasize the literary movement’s countercultural cool over its actual intentions. As I prepped for writing this piece, I re-read William Gibson’s Neuromancer for the first time in a couple of decades. It’s hard to describe the impact the book had on me when I first read it, a teenager growing up in a small Irish provincial town in the 1980s. Part of that was surely the extraordinary language; taking Alfred Bester’s prose style and turbocharging it. But part was also that it was a concentrating lens that made visible a complex set of relations between power, money, information and hustle.

One word that never appears in Neuromancer, and for good reason: “Internet.” When it was written, the Internet was just one among many information networks, and there was no reason to suspect that it would defeat and devour its rivals, subordinating them to its own logic. Before cyberspace and the Internet became entangled, Gibson’s term was a synecdoche for a much broader set of phenomena. What cyberspace actually referred to back then was more ‘capitalism’ than ‘computerized information.’

So, in a very important sense, The Bezzle returns to the original mission statement - understanding how the hacker mythos is entwined with capitalism. To actually understand hacking, we need to understand the complex systems of finance and how they work. If you really want to penetrate the system, you need to really grasp what money is and what it does. That, I think, is what Cory is trying to tell us. And so too Bruce. The nexus between accountancy and hacking is not a literary trick or artifice. It is an important fact about the world, which both fiction and non-fiction writers need to pay attention to.

Love the Hench novels, and your connecting them to early Gibson.