Liberalism transforms plurality from weakness to strength

At least it does when it works right ...

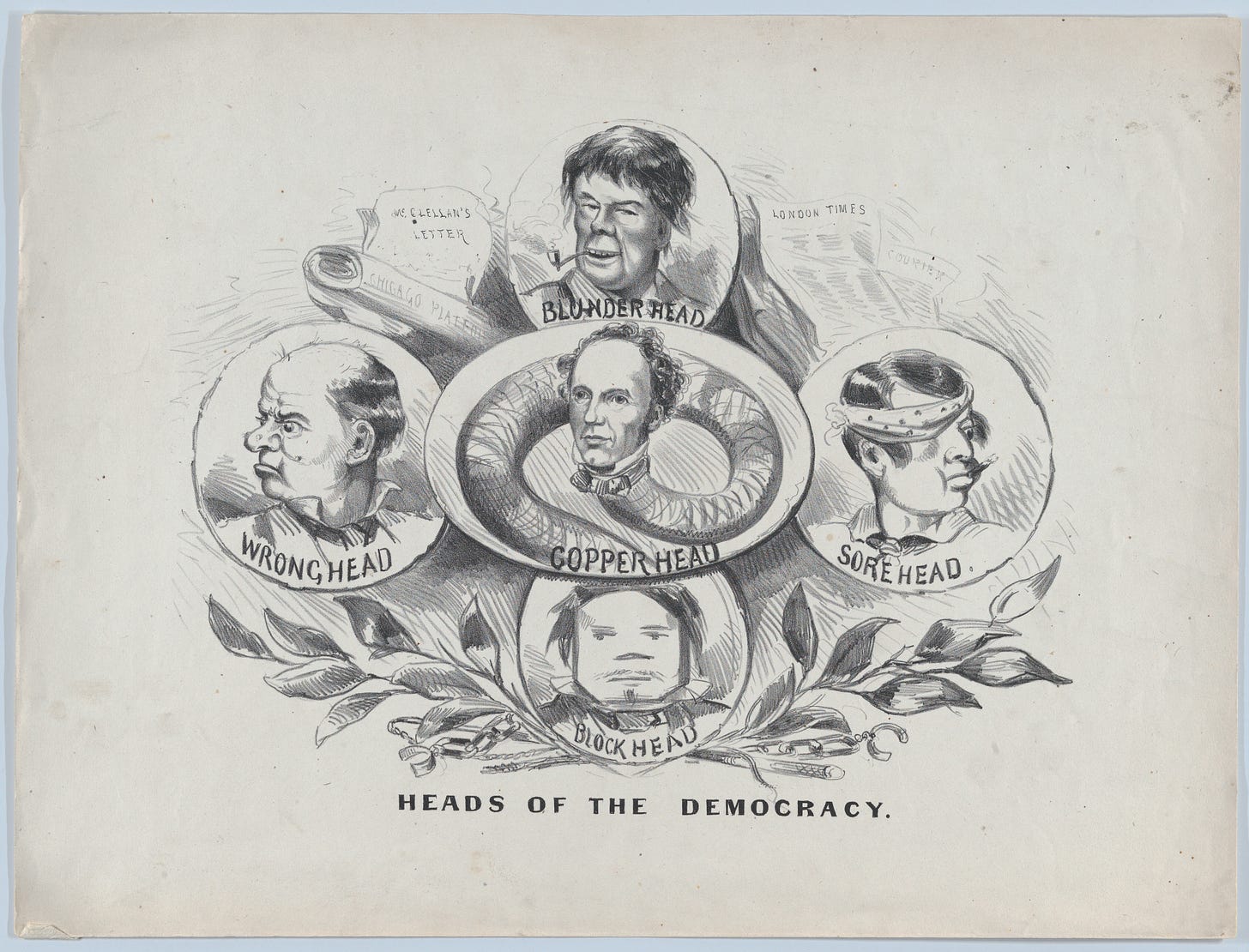

[Image from the Met]

Here’s a trick for reading Ezra Klein’s article in the New York Times yesterday. First of all, read Ross Douthat’s piece offering advice to the Democrats on what they ought do. Then, as you are reading Ezra’s piece, ask yourself: are there important differences between what the two are saying?

Some people seem to read them as minor variations on the same theme. I think that is badly mistaken. The difference between the argument that “the Democratic party should become a moderate party” and the argument that “the Democratic party should be more welcoming to moderates and other people who don’t agree with all their positions” may appear subtle at first glance, but has substantial practical consequences.

The one hectors Democrats, saying that it is “obvious” that they need to move closer towards Republicans’ positions and converge on the center, because voters converge there too. The other argues that Democrats need to deal with the fact that they are a plural party, with many internal disagreements, but that this is not necessarily a bad thing. It reflects the messiness both of practical liberalism and of politics; voters are plural, and public opinion is complicated.

Douthat says that fixing the Democrats’ problems is easy in principle - just look to the median voter and make him happy! Klein’s framework suggests that politics is … political .., a perpetual messy and argumentative process of balancing tensions, dealing with the wants of squabbling factions, attracting and retaining voters who don’t agree on everything at all, and somehow still moving forward. Grace and generosity are crucial to maintaining any viable political coalition. And this is true, whether you begin, as Ezra does, from a position that is closer to the center, or from one that is further to the left. Both face the same practical challenges of forging and maintaining coalitions.

******

Douthat’s advice for the Democrats explicitly channels the “popularist” analysis associated with a particular centrist faction in the Democratic party. Popularism argues that the problem with the Democratic party, very straightforwardly, is the undue influence of its left wing. Douthat’s op-ed is based on a recent report, with lots of public opinion polling, that makes this case at length, and it is remarkably useful because it lays out the basic claims of popularism in a single piece that is short, and easy to access (if you have a NYT subscription or can get someone to share a link).

According to Douthat, Democrats’ problems are “completely obvious” (italics in original): the party “overcommitted to a range of unpopular left-wing positions.” This is “plain to anyone with eyes,” as is the decisive case for moving the party en masse to the right. Those who want to tell other “stories” about what is happening, or to criticize the pollsters are engaging in purposeful “evasion” of uncomfortable truths. Worries about how media changes are reshaping politics, or the electoral system are so many versions of denial. The way to win elections, as always, is to move closer to the preferences of the “median voter.” The only thing that prevents Douthat from claiming the Full Popularism Jackpot, perhaps to his credit, is that he doesn’t cast aspersions on the honesty of the many quantitative political scientists who disagree with this understanding of polls and elections.

I’ll be getting back to my own problems with this simplified understanding of politics below. What is important is that Ezra starts from a different understanding of the Democrats’ problems. And quite explicitly so:

an increasingly bitter debate has taken hold over what the party needs to become to beat back Trumpism. Does it need to be more populist? More moderate? More socialist? Embrace the abundance agenda? Produce more vertical video? The answer is yes, yes to all of it — but to none of it in particular. The Democratic Party does not need to choose to be one thing. It needs to choose to be more things.[my italics]

The problems, on this diagnosis, are less about the issues than the social relationships that can bring together a party with a multitude of views, and make it more attractive to those who have left or haven’t yet committed.

Sometimes people tell me about issues where the Democratic Party departed from them. But they first describe a more fundamental feeling of alienation: The Democratic Party, they came to believe, does not like them. … The structure of American life changed in a way that has made the genuine relationships of politics much harder. Instead of representing many different kinds of people in many different kinds of places, the parties now tilt toward the place in which the elite of both sides spend most of their time and get most of their information. The first party that finds its way out of this trap will be the one able to build a majority in this era.

The professional political classes spend their time online, and their understanding of politics is increasingly shaped by that environment.

The conversations pulsing across these platforms are shaped not by civic values but by whatever proves to keep people scrolling: Nuanced opinions are compressed into viral slogans; attention collects around the loudest and most controversial voices; algorithms love conflict, inspiration, outrage and anger. Everything is always turned up to 11.

Social media has thrown everyone involved at every level of politics in every place into the same algorithmic Thunderdome. It has collapsed distance and profession and time because no matter where we are, we can always be online together. We always know what our most online peers are thinking. They come to set the culture of their respective political classes. And there is nothing that most of us fear as much as being out of step with our peers.

The result is that the Democratic party has become a much more unwelcoming place for people who are out of step with an online consensus that favors a particular kind of online purity. What we want instead is liberality:

It flowered into religious tolerance when that idea was truly radical — when mainstream thought held that the violent persecution of heretics was an act of charity because it would keep others in the church. Liberality proposed a different way of relating across disagreement and division. It built toward liberalism’s great insight, what Edmund Fawcett, in his book “Liberalism: The Life of an Idea,” calls liberalism’s first guiding idea: “Conflict of interests and beliefs was, to the liberal mind, inescapable. If tamed and turned to competition in a stable political order, conflict could nevertheless bear fruit as argument, experiment, and exchange.”

Today, political tolerance is harder for many of us than religious tolerance. Finding ways to turn our disagreements into exchange, into something fruitful rather than something destructive, seems almost fanciful. But there is real political opportunity — dare I say, a real political majority — for the coalition that can do it.

This seems to me to be to be recognizably right, even to many people who are on the left. There is a reason why many people who spend a lot of time on Bluesky and bristle at criticism from outsiders, sometimes joke about how Bluesky can be unbearable. Its problem is not the mob politics of Twitter, but the stifling consensus of the village, where those who don’t adhere to the local consensus are made to feel unwelcome and unworthy.

The fundamental message of Ezra’s piece is not that the Democratic party needs to become a moderate party. It is that it needs to become a party that is welcoming to moderates, as to others who don’t completely share its beliefs, if it is to succeed. Figuring out ways to manage - and even welcome - differences inside the party is not only crucial in itself, but may help it to build stronger and more enduring coalitions among citizens too. They too are more likely to be attracted by a party that is more interested in bringing people in, than in telling them what they ought to do or who they need to be.

The lesson of this is not that managing pluralism is easy. Pretty well by definition, it is anything but. Instead, it’s that building tolerance, and figuring out how to work through the inevitable messiness and conflict, can not only create common purpose internally, but attract others to your cause. The small-l liberal bet is that plurality is not simply an inescapable problem, but an enormous source of political strength. It is realizing that strength involves bridging differences rather than seeking to eradicate them.

*******

There are two obvious risks in this kind of liberal appeal to pluralism. First, such appeals may be prettier seeming in the abstract than they are in reality. They may underestimate the practical political difficulties involved. Second, they may be unconsciously or deliberately loaded with their own ideology: calls for moderation cloaked in the language of pluralism.

It helps, then, that there is a leftwing version of this case, rooted in the pragmatic challenges of movement organizing. If anyone wants to accuse the people of Hammer and Hope of being moderate sellouts, good luck to them! Some while ago, this publication (it’s lively and excellent if you haven’t read it) published a very useful interview of Doran Schrantz by Hahrie Han, on the problem of building practical bridges across groups with different ideologies. Schrantz was a key organizer of the effort to build a multiracial coalition in Minnesota, bringing together different social and religious groups. She describes the challenges of holding this coalition together after the repeal of Roe v. Wade.

For example, in the middle of our election work in 2022, Roe v. Wade was overturned. … How in the hell are we going to hold our base together through this? We have a significant suburban base of primarily white women who are normie to progressive Christians — they are going to want to motivate themselves and others around this issue. But I knew that the Muslim coalition, parts of the rural organizing project, and the Black barbershops and Black congregations would not have the same reaction. So I had to step up as a political leader. I called key people across the organization and built a path to unpack it together.

So … we negotiated. Can we actually have mutual interest in this moment? The group decided that ISAIAH would not make any statement on the fall of Roe v. Wade as an organization. However, we agreed that staff and leaders of Faith in Minnesota, our C4 expression, could organize in their own communities grounded in their own interest. The Faith in Minnesota coalition were essential actors in flipping the Minnesota State Senate to DFL control, which staunchly supports reproductive freedom. The DFL majority enshrined reproductive freedom in Minnesota in a statute. If we had torn the organization apart at that moment because we were not able or willing to do our own internal politics grounded in our shared power, would that have been the best way to achieve our values in the world?

Very possibly, Doran Schrantz and Ezra Klein would have lively disagreements on the particulars if they ever talked together. But as far as I can see, they are as one on the fundamental question of how to build power in a world of real, grounded clashes among your constituents. It involves creating strong relationships of mutual respect between groups that often have sharp differences. Where those divisions are sufficiently deep that they might tear the coalition apart, it is often better to recognize and to allow this disagreement than to demand that everyone follow the party line. That can help facilitate progress - even on divisive issues such as abortion.

******

One final point. All this - and to be clear this whole section is me talking, not Ezra - doesn’t just imply that there is something awry with the left wing of the Democratic elite. It points to problems with the centrist wing too. Each has been captured by its own ideological simplifications. The popularist obsession with the median voter that Douthat says is quite as ideologically stifling in its own way as left-leaning villagism.

If you truly believe that the voter bang at the middle of a one dimensional single-peaked distribution of opinion is the pivot point of politics, you are a centrist by force of axiom. You are less likely to worry about whether voters think there is something fundamentally wrong with politics as a whole. Nor will you be particularly concerned with flaws in the media structures through which voters perceive parties and policies. Most fundamentally, your view of politics will tend towards the apolitical - politics is less about the slow boring of hard boards, than it is about the technocratic adjustments of policies and messages to what the median voter wants, as measured through a plethora of opinion polls and other measures.

Obviously, this is a caricature - few popularists are nearly as technocratic as that* - but it’s a caricature with the same force as the cartoon image of the lefty who cares more about ideological purism than winning elections. It usefully identifies loose intellectual tendencies, and the kinds of justifications that are deployed unconsciously or consciously to support them. If the left tends to overplay the importance of internal unity at the expense of the compromises required by actual electoral and movement politics, centrists tend to big up the awesome moderating power of thermostatic public opinion, and to dismiss the problem of bringing different factions along as mere pandering to the “groups.”

Both tend towards nostalgia for simpler times at the expense of trying to figure out the more complex age that we are in, and how to address it. My biggest objection to Douthat’s article is not that he overestimates the benefits of centrist messaging, though he surely does. It’s that his simplistic - and, quite literally, one dimensional - framework filters out all the other important environmental changes that are happening. Instead, he presents a cartoonish vision of politics as a pendulum which inexorably swings back and forth along one narrow ideological axis as politicians repeatedly mistake the nature of the problem.

But as Lee Drutman - one of the political scientists whom Douthat snipes at - implies, that mistakes the disease for the cure. We live instead in a world of what complexity scientists would describe as high dimensionality, where lots of complex phenomena interact in highly unpredictable ways. One of these high dimensional problems is public opinion itself - which is in part entangled with these bigger difficulties, and in part its own complex space. To do better, parties need to better explore the space of possible solutions. But that is ever more impossible as our available list of political solutions becomes increasingly confined to those that are compatible with a single dimension of partisan contention.

Lee’s solution to this is to open up the space of party competition. Jenna Bednar proposes remaking federalism. There are other proposed paths to opening up diversity, so that we are not stuck desperately trying to apply low dimensional solutions to very high dimensional problems.

This provides another possible experimentalist justification for the kind of liberalism that Ezra proposes. Exactly contra Douthat, the ways out of our predicament are not obvious, and going all-in on rhetoric and simplistic solutions based on opinion polls are likely to make things worse (look at the Labour government in the UK right now to see how the pathologies might play out). Actually existing centrism dampens down some sources of useful variety in discovering ways out. Actually existing left-purism dampens down others.

What I think most is valuable about Ezra’s argument is that it opens up debate rather than closing it. Don’t opt for just one approach. Choose to be more things. Figure out how to build a party that can manage those tensions. This is valuable in itself, and also likely attractive in bringing other people in. Try to figure out which things work and which do not. That is valuable in other ways (which Ezra might or might not be hinting at in his argument, though it flow from Fawcett’s mention of experimentation, but which I am here arguing for explicitly).

Succinctly: some of the great value of liberalism, including its classical, centrist and social democratic variants, is that it acknowledges the need to manage diversity and pluralism internally. Some is that - unlike its major adversary right now - it emphasizes the value of diversity and pluralism in society as well. Some is that - if done right - it respects the worth and value that other people who are currently outside the coalition have, and looks to bring them in. And some is that it can employ this useful variety to experiment, discovering better ways to live together and to figure out how best to mitigate or solve the enormous problems we all face.

* Although this Comrades: True Centrism Has Never Failed, It Has Only Been Failed exhortation perhaps comes close.

[various small edits have been made throughout since first publication - I do this for all my posts, but there were higher numbers than usual of grammatical glitches, slight misphrasings etc]

I did read both columns, and I think your points are well taken. One reason I read Douthat is because he's intelligent, but he comes from a different perspective. I don't always agree with Ezra Klein but I think his points in this column are quite sound. I liked his referral back to the understanding of liberalism as inherently tied to tolerance. We need more of that - all the way around. Tolerance not for hateful behavior, but for different perspectives and values.

The question isn't whether the democratic party wants to appeal to as many votes as possible (aka winning elections), but how it gets there. And one challenge is that "liberality" is in tension with clarity of vision. This is where many leftists have the biggest disagreement with the Ezra Kleins of the world, which is that they argue that effective politicking doesn't happen primarily through negotiating across constituents, but rather through an energizing vision that different constituencies can get behind.

The second issue, particularly in the current moment is that politics isn't just about ideas and even interests, it can boil down to tangible rewards and punishments. Trump 2.0 makes this all too clear. A CEO who supports Trump will avoid becoming a target and might even get preferential treatment. Meanwhile, there's nearly no downside if the Democrats win. Contrast that to betting against Trump. Same goes for constituents. Even within the party, the big tent approach requires arm-twisting or rhetorical displine, but where's the weight behind the threats if it's all about mutual respect.

The appeal to big tent liberalism feels like a misdiagnosis of the challenges faced by democrats and the left. Trump has proven adept at attacking "big tent" opponents a clear vision or case. And the unwillingness (or inability) of democrats to commit to offense has emboldened opponents and alienated supporters. Yes--democrats need to connect with and stop chasing away voters. But that's one of many things they need.