Dictators are plagued by information problems too

We've no good evidence that China does it better than the U.S.

Noah Smith has a toy model of the differences between liberal democracies and authoritarian systems that he wants to be argued out of, since it suggests that authoritarian systems might win over the long term. And I’m happy to oblige! I’ve no good answer to the question of whether democracy will prevail over authoritarianism, or vice versa in the long run (I do have hopes and beliefs). But I do think that there is a missing empirical element in Noah’s account of Chinese authoritarianism as an information system. When you put it in, you get a different and much more qualified comparison.

The key parts of Noah’s argument, as I read it.

China hasn’t yet proven the superiority of its system, but its successes raise the uncomfortable question: Can this be what wins? Can universal surveillance, speech control, suppression of religion and minorities, and economic command and control really be the keys to national power and stability in the 21st century? … So here you go: a theory of how totalitarianism might naturally triumph. The basic idea is that when information is costly, liberal democracy wins because it gathers more and better information than closed societies, but when information is cheap, negative-sum information tournaments sap an increasingly large portion of a liberal society’s resources.

… Hayek had a theory of why capitalist economies would outperform command economies. His theory was all about information aggregation. … it’s easy to think of representative democracy as another information aggregation mechanism — a way of finding out what voters want and putting those wants into policy by simply letting people choose their leaders. And it’s easy to think of free speech as an information aggregation mechanism — a way of finding out what people think through a “marketplace of ideas”.

… Economists take Hayek’s ideas very seriously, and in the decades following his seminal work there has been a lot of theorizing about the economics of information aggregation. … Grossman and Stiglitz assume that information about the value of a stock is costly. … Hirshleifer, on the other hand, assumes that information about fundamentals will eventually come to light on its own. … But at the same time, he assumes there’s a big private reward for anyone who goes out and figures out that information in advance, because that person will be able to trade on the temporary mispricing before the information becomes public. So there’s a tournament between a bunch of investors who all try to beat each other to the punch. This effort is wasted, since the information would have come out on its own soon anyway. … In the world of costly information, anything that brings down the cost of gathering information makes the aggregator — in this case, the stock market — more efficient. But in the world of cheap information, competition over that information produces waste and makes the market less efficient.

So if liberal democracy is mainly a collection of information aggregators, we can use these two papers as metaphors to imagine two very different worlds — a world of costly information, vs. a world of cheap information. In the world of costly information, liberal institutions like free markets, free speech, and elections reduce information costs, and make the ultimate social outcome more efficient. But in a world of cheap information, tournament effects — costly, wasteful, negative-sum competitions over the private control of information — might dominate. … my scary little conjecture is that as information gets cheaper, liberal information-aggregating institutions might become less and less useful, while totalitarian information control goes from a liability to an asset because it limits wasteful tournaments.

So this is an interesting argument. I’ve spent a fair amount of time over the last few years, noodling about democracy and authoritarianism as information systems (mostly with co-authors, who are far more intelligent than I am). But, not being an economist I’ve not read the specific Grossman and Stiglitz paper, and I’ve never even heard of the Hirshleifer article.

The idea that Noah is playing with, I think, is as follows. We look at authoritarian systems as information dampeners - a lot of what they do is very deliberately aimed at blanding disagreement down, and spicing apathy up, so that visible public opinion converges on an unanimous roar of assent from the masses. We think of democracy as a set of mechanisms for open information aggregation. By and large, we expect that open information aggregation will have positive consequences for the general weal, and information dampening as having bad ones. But what if we are wrong? In a world where information is (a) cheap, but (b) having it early gives you an advantage, there is likely to be a lot of wasteful and perhaps destabilizing contention and shouting in an open information system, but closed ones may be able to manage it better.

While this is prima facie plausible, my first response is to ask whether, in fact, authoritarian systems do work in this way in the specific and practical rather than the aggregate and theoretical. Which means that my second instinct, necessarily, is to ask someone who would know! I am not a China expert, so I depend very heavily on the knowledge of those who are. For questions like this, I’d normally turn to Jeremy Wallace, who is about to become a colleague at Johns Hopkins SAIS (yay!), and who works on information processing in the Chinese state, or Yuen Yuen Ang (also at Johns Hopkins), who does comparative work on China’s political economy. But neither of them are around over the summer, so I’m turning instead to Jeremy’s recent book, Seeking Truth and Hiding Facts: Information, Ideology and Authoritarianism in China. Any blunders or errors of interpretation are completely my own.

Noah talks, rightly, about the inefficiencies of tournaments in U.S. decision making.

There is plenty of evidence that U.S. politicians spend much of their time campaigning for office rather than governing. Much of that time is spent raising money for campaign messaging. Every member of the U.S. House of Representatives is up for reelection every 2 years, requiring a continual cycle of fundraising; incoming House members are advised to spend four hours out of every day raising money. Other estimates give a number of 30 hours a week. … This is an information tournament — only one candidate can win any election, but all the candidates have an incentive to spend more resources shouting down their opponent. … the fact that your average legislator is basically just a fundraiser seems like a recipe for a dysfunctional, ineffective nation.

China’s leaders are not democratically chosen, which probably makes them worse at aggregating the preferences of the populace. But it’s at least conceivable that the Chinese system might give rulers much more time to do the actual business of ruling.

But the interesting thing is that Chinese policy making is run via a tournament system too.

As the title of Jeremy’s book suggests, there are many serious problems in how the Chinese state aggregates information. In fairness, it has a horrendously difficult task - China is a huge country, with a necessarily dispersed administration. But the tools that it has used to govern the country until quite recently - sparse summary statistics and competition among officials, lead to their own very particular dysfunctions. Here, I’m going to summarize Jeremy’s detailed history crudely and simplistically. If you want the real thing, read his book, not my potted version of it.

One of the key steps towards China’s modern version of autocracy was Deng’s decision to push for better educated “cadres” - elite Communist decision makers - to run the Chinese state. This went hand-in-hand with efforts to improve quantification - the eclipse of seat-of-the-pants rule-making with formal measures of outputs and prices, and some recourse to public surveys to find out what ordinary people thought. Very crudely simplified: the idea was that better policy making required both more intelligent officials, and more reliable quantitative measures to check what they were up to, and whether they were succeeding or failing. As Jeremy notes, there are significant similarities between this set of reforms and the parallel victory of neo-liberalism in the U.S. state described by scholars such as Elizabeth Popp Berman.

Above all, Chinese leaders wanted economic growth - and they created a system that was geared to produce it. Hence promotion of party officials depended to a substantial degree on how well they were forwarding the national agenda, as measured via a “limited, quantified vision” based on a few key summary statistics.

Again, China is huge! It is really hard for the people right at the top to see what is happening at the levels beneath. So they tried to coordinate through a mixture of incentives (produce growth in the part of the country you are responsible for, and your career will prosper) and monitoring via summary statistics for GNP, agricultural and industrial output etc.

We don’t know nearly enough about how this system works in practice. In Jeremy’s description: “While particulars of the cadre evaluation system maybe have been omnipresent to those inside it, the external scholarly study of this system has been hampered by the regime’s opacity, manifested by limited interview information or documentation of actual evaluation forms or score sheets.” But what we do know suggests that it has had very important consequences, even as it morphed into bigger and vaguer measures over time, and that GNP/GDP has historically been the key indicator: “In 2007, a headline blared, ‘if not GDP, Then What Will Be Assessed?”

The result combined a tournament system with backscratching among different political clans of officials. In Jeremy’s summary of the literature:

Hongbin Li and Li-an Zhou saw competition along these lines as a tournament, where the best performers went on to the next level to compete again. This tournament hypothesis is often placed against a factional explanation of promotions … A third, more nuanced scenario connects these two strands of argumentation.

Nor is this just Jeremy’s idiosyncratic interpretation. A quick Google scholar search for “China cadre tournaments” suggests that it is a reasonably common theme in the literature

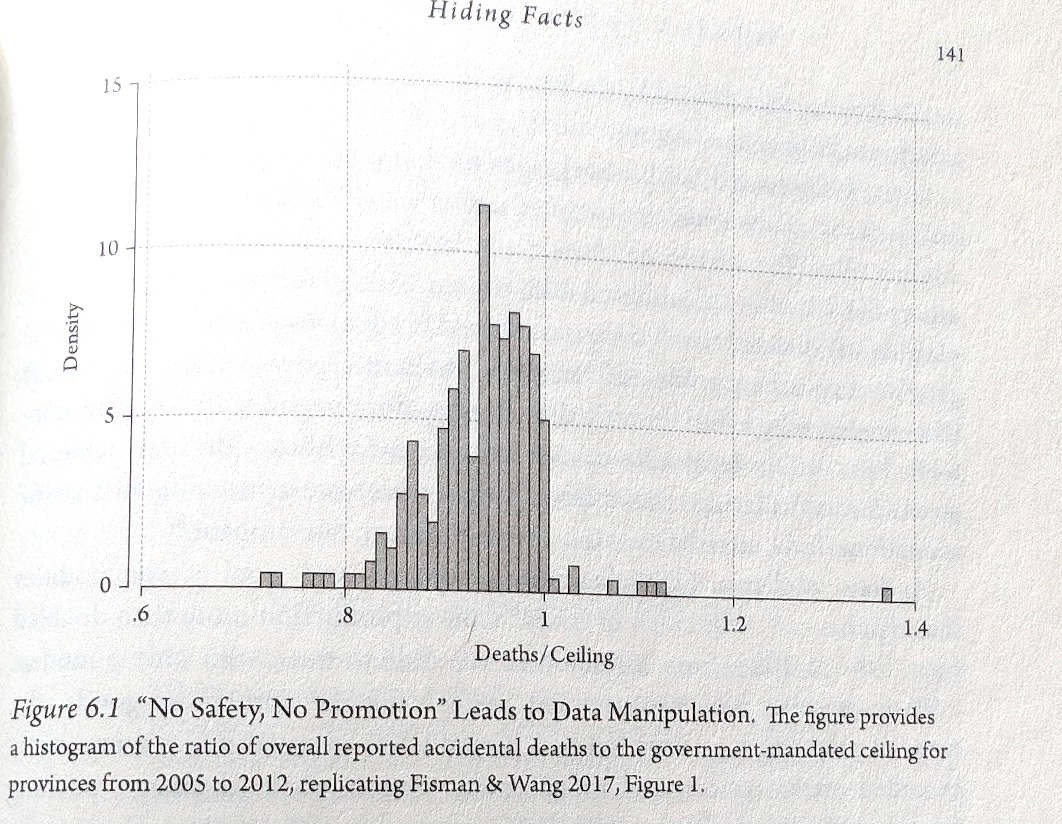

The consequences of these tournaments have been as one might have expected. Unsurprisingly, officials have focused on the measures that got them bonuses, and affected their bonuses and chances of promotion, and were less interested in solving problems that would not help them win through to the next round. They have focused on gross production measures rather than specific efficiencies of production. They have endeavored to shut down channels of complaint that might publicize failures that were embarrassing to themselves or the regime. They’ve juked statistics to make themselves look good (nb. what happens to the distribution past the ‘you are in trouble because you have too many industrial accidents in your province’ in the graph below). They have fought economic ‘wars’ with officials in other provinces to capture the value of commodities for themselves.

Finally, these incentives have played a quite substantial role in the artificial Chinese property boom, and the accompanying explosion of local government debt. If you want to goose local GDP, one great way to do it is to build lots and lots of housing, even if there isn’t much demand for it. Sooner or later, someone is going to have to pay for it, or deal with the vexed problem of what to do with unwanted tower blocks of apartments, but if you are an ambitious young Chinese official, who will likely have moved on to a different and better position by then, why should you care? That’s someone else’s worry. The IBGYBG problem is not unique to Wall Street.

This system has arguably had real benefits for China: GDP growth has gone up, and not just in the fake statistics. But it has increasingly distorted the Chinese economy. Xi has made speeches suggesting that the limited quantified vision is not, after all, all that, but what comes next is a little blurry. It is very hard to steer Leviathan (and few Leviathans are as Old Testament as the Chinese state), without highly stylized quantitative indicators and feedback mechanisms.**

You certainly shouldn’t attribute China’s property market crisis to the cadre system on its own. There is a whole complex political economy behind it. But the until-recently-dominant system of cadre tournament plus GDP monomania is very plausibly a significant skein within the messy tangle.

So the broad lesson that I take from this is that (a) tournaments are endemic in US politics, creating a lot of waste, and badly skewing policy makers’ incentives, and (b) tournaments are endemic in Chinese politics, creating a lot of waste, and badly skewing policy makers’ incentives. It still could be that the tournament problem is much worse in the US than in China. But figuring that out would require some actual proper serious comparative research. What evidence there is suggests that tournament style contention happens in China, but in less publicly visible ways.

Noah can feel a little relieved that his simple model does not, on its own, imply that democracy is doomed to succumb to the superior ability of authoritarians to capture cheap information. But, this is quite different from saying that we can feel assured about the superiority of democracy. Instead, it suggests that we don’t know enough to be able to begin to answer the big underlying questions.

Here, I’m bullish about the benefits of doing the kind of comparison that Noah suggests, comparing autocracy, democracy and markets as systems of information aggregation. I would be bullish, since as I’ve already said, this is a topic that I am enormously interested in. Equally, whatever insights I have on this aren’t really mine - again, they are building on co-author relationships, or surreptitiously repackaging things that Charles Lindblom or Herbert Simon said a couple of generations ago. I’m particularly taken with Simon’s account in The Sciences of the Artificial, which could (loosely) be summarized as highlighting the gross inadequacies of our individual cognitive architectures, and our consequent reliance on a variety of external machineries such as markets, hierarchy etc to think collectively and to coordinate. As Cosma and I have written, large language models can be understood from this perspective as no more or no less than a new kind of machinery.

Equally, I’m somewhat skeptical that we’ll ever be able to find satisfactory answers to big questions such as ‘will democracy beat autocracy or vice versa’ that are difficult (as best as I can see) even to pose in precise terms, let alone to answer. These controversies turn on questions that are just too big and complicated to be readily boiled down while retaining some real flavor of their original meaning. But I do think we can come up with tentative responses to other, slightly less ambitious comparative questions, that might still be pretty useful. What are the respective informational vulnerabilities of autocracies and democracies? Will AI supercharge authoritarian government control of their societies? And so on.

* The chapter in Underground Empire that I was most nervous about was the chapter on China, because neither Abe or I read Chinese. We wrote on the basis of other people’s interpretations and hoped we were not screwing it up. So far, no-one has yelled at us in public about what we got wrong, so I am beginning to feel very cautiously hopeful.

** As I finish revising this for publication, I see that Brad DeLong has published a magnum opus on Dan Davies’ book on cybernetics. Without providing incriminating details, one of the best conversations I have witnessed in the last few years was between DD, Dan Wang and Ben Recht on the topic of cybernetics - DW is in the throes of writing a book that talks about engineers and the Chinese state.

Following climate policy, what's really striking is the role of China's provincial governments in keeping coal going, which is always tied to corruption. I had a go at this here

https://independentaustralia.net/politics/politics-display/coal-in-china-the-good-the-bad-and-the-ugly,15470

The central government has blunt instruments (up to and including executions) to control provincial officials, but no easy way to get access to the information they control

Are you conflating “speech” as in free speech with “information” as a description of a true state of affairs. But speech is a description of a possible state of affairs, not to be assumed as “true”. If there is a coin that might be heads or tails, and I say “the coin is heads” you can’t tell prima facie whether I am telling the truth, lying, or bullshitting. So in a social-media democracy where speech is maximally unrestrained, information entropy is maximized, and it is costly to ascertain the truth of situations. Conversely if there is an accessible “authority” in a position and disposition to speak truth, access to truth is cheap.

So it all depends, as usual. Whether your authoritarian is trustworthy on the one hand, or your citizenry is well-behaved on the other. Efficient nation-states would seem to require both, so yes, council of despair I suppose.